A public sphere not mediated by state television or controlled narratives. People simply talking to each other, in real time, in a forum beyond the reach of power.

That is the fear.

I say this not as a theorist or a politician, but as the host of a nightly call-in program that attempts, modestly and imperfectly, to make such exchanges possible.

The experiment is simple.

There are no slogans, no marching crowds, no images calibrated for cable news. Instead, there is a microphone, a live line, and an invitation so unassuming it almost sounds apolitical: talk. Not perform. Not chant. Not rehearse ideology. Just talk, to one another, in real time, about what has gone wrong, what hurts, what frightens, and what still feels imaginable.

A society that cannot speak to itself is condemned to repeat its errors. A society that can speak cannot be governed indefinitely by myth.

Fractured by fear

Iran is among the most politicized societies in the world, yet genuine political dialogue is structurally impossible.

Families learn which subjects to avoid at the dinner table. Schools train obedience rather than inquiry. State media speaks incessantly but listens to no one.

Even social media, often romanticized as a space of resistance, is fractured by fear, surveillance, and mutual suspicion.

The result is not apathy, but exhaustion.

Questions accumulate without resolution. Why does a country rich in oil and gas fail to provide reliable electricity? Why do rivers vanish while neighboring desert states manage water abundance?

Why does each generation inherit fewer prospects than the one before it? Is war inevitable? Is collapse? Is change possible without catastrophe?

These questions never cohere into shared understanding.

Online, coordinated campaigns flood debates with distraction and distortion, contaminating the very spaces where collective reflection might otherwise take shape. Fragmentation serves power.

A society arguing with itself is a society distracted from those who govern it.

The most dangerous conflict in Iran today is not between the state and the people, but among the people themselves, along ideological, generational and emotional fault lines.

In the aftermath of the recent brief war with Israel, many Iranians found themselves at a crossroads, unsure whether the future demanded silence, rupture, or something harder and more fragile.

Dialogue, in this context, is not reconciliation with power, nor a plea for moderation as a moral posture. It is not an elite exercise in rhetoric.

Real dialogue is untidy. It requires listening to voices one distrusts. It rests on a radical premise: that no one, neither the dissident nor the conscript, neither the exile nor the factory worker, is disposable by default.

The right to speak, and to hear

On my program, I try to create space for that premise to be tested. The format is open, live, and unfiltered. Callers speak without ideological vetting. What matters is not agreement, but participation.

Recently, callers from Tehran, Rasht, Shiraz and Zahedan spoke openly about leadership, foreign intervention, a monarchy versus a republic, internet shutdowns, nonviolent resistance and the ethics of accountability if the Islamic Republic falls.

Some urged speed. Others warned against vengeance. Some placed hope in figures abroad. Others insisted that change must be rooted domestically.

At one point, a caller argued that anyone associated with the state must be punished. Another responded that a society cannot be rebuilt on the promise of mass retribution. Justice, he said, requires distinction, between those who committed crimes and those who merely survived within a coercive system.

In most democracies, such an exchange would pass unnoticed. In Iran, it is revolutionary.

It is precisely this kind of public, imperfect, unscripted reasoning that authoritarian systems fear most.

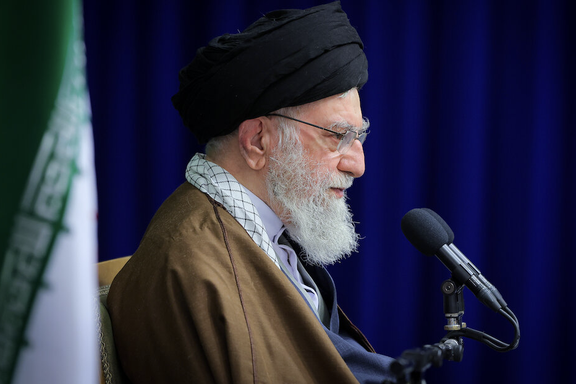

The Islamic Republic today appears brittle. Its supreme leader speaks of progress while citizens search for medicine and hard currency. Parliament performs loyalty. The judiciary enforces obedience. State media manufactures fake optimism. Yet none of these institutions command belief.

What they cannot tolerate is unity that does not require uniformity.

A national conversation produces legitimacy, among citizens. It generates shared language, moral boundaries, and, eventually, political imagination. Once people agree on what the problem is, power loses its monopoly on explanation.

Speech connects. Connection organizes.

Silence, by contrast, is a slow death. It corrodes trust. It persuades people that their doubts are solitary.

They are not. Iran does not lack courage. It lacks space.

Every Thursday night, that space opens briefly on my show, long enough to remind people that the most radical demand is not vengeance, or even freedom, but the right to speak, to be heard, and to understand one another before history forces the conversation in blood.

That, ultimately, is what terrifies Iran’s supreme leader.