To many viewers it looks like a cultural opening: a genre long associated with underground resistance now visible on mainstream screens.

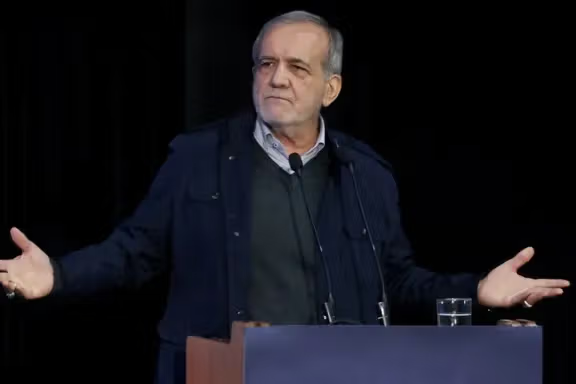

But researcher and artist Siavash Rokni, a postdoctoral fellow at McGill University in Montreal who studies Iranian youth culture, pop music and the communication dynamics of social movements, argues that that the reality is more complicated.

“It is a public relations performance,” he said. “It is fooling a lot of people, and we need to stop being fooled by it.”

Rokni has followed the evolution of Iran’s rap scene across five generations. He sees the new appetite for rap not as legalization but domestication, turning underground culture into something profitable and controllable.

Entertainment shows and “normal” rappers

One of the most watched programs in this space is BaZia, hosted by a former Iranian state television personality now living in Turkey. According to Rokni, the show’s guest selection and narratives suggest an ongoing connection with Iran.

“Technically speaking, he is no longer connected to the system,” Rokni said. “But the way he chooses his guests shows there is a connection.”

The rappers appearing on BaZia help normalize a particular type of rap that is not inclusive of all aspects of this cultural practice. Many of the same rappers featured on BaZia are now set to appear in a new rap-themed program hosted by him called GANG. Rokni says it shows how this was part of a larger plan to create momentum for the new show while normalizing a particular narrative of regime approved rap.

The narrative, Rokni said, “comes very slowly” through a sequence of interviews. Artists describe performing abroad but wanting to return. Producers talk about the economic advantage of bringing rap back while being able to control the content.

Money, control and aesthetics

Much of Iran’s music economy is in the hands of a profit-minded clique, Rokni said.

“The people who are running this oligarchical capitalism are connected to the Islamic Republic,” he said. “They just want to make cash.”

He stressed that the motivation is not necessarily ideological. Many simply benefit from the system’s structures.

The appearance of rap on screens has been accompanied by pressure and arrests behind the scenes. In early October at least five rappers and a composer were detained in Tehran and Shiraz, according to the Center for Human Rights in Iran.

Security forces raided homes, seized phones and recording equipment and transferred the men to detention.

Within days videos appeared on their Instagram accounts with shaved heads and visible tattoos, apologizing on camera. Lawyers told CHRI the accounts had been taken over by cyber police.

One of the most high profile cases remains Toomaj Salehi, whose lyrics became an anthem of the Women Life Freedom movement.

He was arrested, abused in detention, sentenced to death, released on bail and then rearrested after publicly describing his treatment. Supporters say he is targeted because he refuses to leave Iran or be silent.

Female rappers face even greater constraints. Iran bans solo female singers from performing publicly or releasing their own vocals, forcing artists into exile or underground spaces. Studios refused to record them and venues were raided for illegal performances.

Why normalize rap at all?

Rokni traces the logic back to then Iranian president Mohammad Khatami era when the government offered small cultural openings to create a sense of possibility.

“You free some cultural restrictions and reconcile with the people,” he said. “You give hope. And that can be taken away very easily.”

He called this strategy dishonest. Licensing and televised satire, he said, do not signal reform. They are tools for narrative management.

Oppression, he argued, is often brief.

“They put a lid on it,” he said. “But the program starts after that.”

The backlash against licensed rappers, especially those connected to the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, has been emotional. Some consider state approved albums a betrayal. Others see economic survival.

Rokni believes the solution is parallel economies, enabling musicians to make money without going through state linked producers or licensing offices.

“Do it yourself,” he said. He pointed to artists who built audiences through Instagram and streaming platforms.

In today’s Iran rap carries two meanings. One version is polished, licensed and safe. The other remains underground created by musicians who refuse to compromise.

Both exist at once but only one is protected.