Instagram pages of two Iranian female singers taken offline by police

Authorities in Iran have blocked the Instagram pages of two female singers as part of an intensifying crackdown on women’s public performances and online presence.

Authorities in Iran have blocked the Instagram pages of two female singers as part of an intensifying crackdown on women’s public performances and online presence.

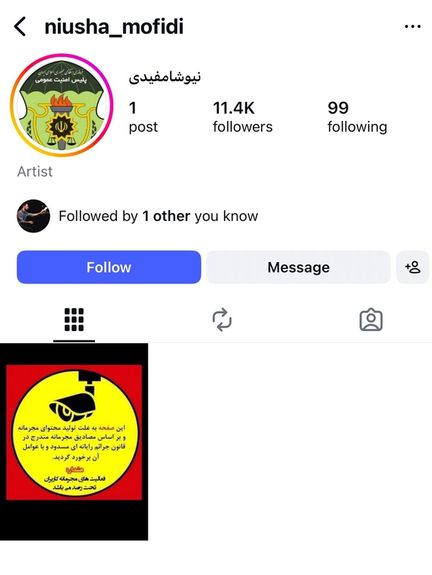

Iran’s cyber police, known as FATA (Iran’s internet crime enforcement agency), blocked the account of Niousha Mofidi, a young woman who performed solo at a concert by Iranian pop singer Hamid Hami.

All posts on her Instagram account, which had nearly 12,000 followers, were deleted. Security officials said the page was closed for “producing criminal content.”

A video shared on social media showed Mofidi singing along from the audience while Hami told others, “Let her sing,” then remained silent so her voice could be heard alone. Mofidi had previously posted videos of her singing on Instagram.

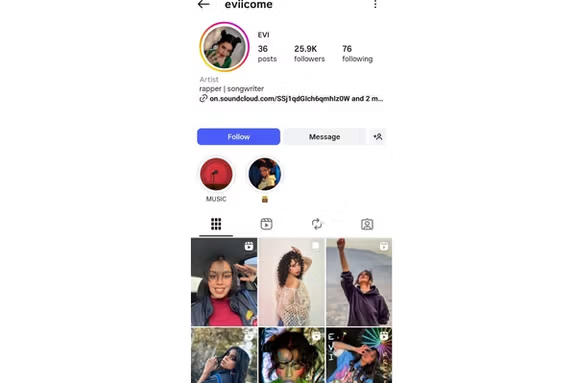

The Instagram account of Iranian rapper Evi, which had nearly 26,000 followers, was also taken offline on Monday. She had previously said security agencies contacted her, demanding she delete her page within 24 hours—a demand she refused.

“I will stand with my people for the rest of my life and will not accept anything that contradicts living freely, even if it is presented in the name of religious law,” she said in a post.

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, women in Iran have been banned from singing in the presence of men, based on religious interpretations. The policy ended the official careers of female singers active before the revolution and pushed their work to the margins.

In recent months, repression against singers and music activists—particularly those opposing the mandatory hijab—has intensified.

More than 160 artists, civil activists, and organizations, including 19 based inside Iran in April condemned the government’s increasing crackdown on female singers, describing it as part of a systematic effort to suppress women and reinforce a gender-discriminatory system.

At least five thousand contract workers at the South Pars energy hub in Asaluyeh staged one of the largest labor protests in Iran in years on Tuesday, defying heavy security pressure and warnings from authorities.

Workers from 12 South Pars refineries refused to report for duty and instead marched toward the Asaluyeh governor’s office in a rare mass demonstration over wages and job security, sources told Iran International.

Despite roadblocks, security deployments, and threats issued in the days prior, the protest drew unprecedented numbers from across the gas complex.

The Council for Organizing Protests of Informal Oil Workers described the march as “a magnificent procession,” while the Free Union of Iranian Workers called it “one of the biggest protest gatherings in Iran’s oil industry in nearly five decades.”

State-linked outlets sought to downplay the scale, describing it only as “a protest of a group of workers” without mentioning turnout numbers.

Labor organizations said authorities had issued direct warnings to workers, including text messages from the South Pars Gas Complex and threats from refinery security units.

Security and police forces had tightened control over all access routes to Asaluyeh, stopping vehicles carrying workers from reaching the rally.

Asaluyeh is a port city and industrial hub located in southern Iran on the Persian Gulf coast, in Bushehr Province. It is best known as the center of Iran’s South Pars/North Dome Gas Field, the world’s largest natural gas field shared between Iran and Qatar.

Labor union support

The Syndicate of Workers of the Tehran and Suburbs Bus Company issued a statement backing the South Pars workers, calling their demands “legitimate, humane, and long overdue.”

"The awareness, solidarity, and resolve of Iran’s working class, while independent organizing and collective resistance remain the only paths to securing workers’ rights," the statement said.

In a related development, a three-day simultaneous strike took place at nine onshore rigs and two offshore rigs of the North Drilling Company, Telegram channel Afkar-e Naft reported on Tuesday.

Iran wartime cyber operations were wide enough to potentially reach every single Israeli citizen during the 12-day war in June, the head of Israel’s National Cyber Directorate Yossi Karadi said at a university forum on Tuesday.

Karadi told the Cyber Week 2025 conference at Tel Aviv University that Tehran launched 1,200 separate information campaigns including text messages and social media posts during the conflict, each targeting thousands of Israelis simultaneously.

“Iran tried to reach every citizen in Israel – and not just once,” Karadi said. “They had hacked into parking and other road cameras to track the movements of Israeli VIPs, with the aim of building operations to target and harm them.”

The extent of the cyber war between Iran and Israel during the June conflict has not been fully detailed by the Mideast arch-foes, which both claimed vast successes in the cyber arena.

“When the Weizmann Institute was hit by a missile, the attack did not start there. A short time before, the attacker sent threatening emails to faculty members. At the same time, they took control of a street camera overseeing the building that had just been bombed,” Karadi said.

The Weizmann Institute of Science, located in Rehovot, is one of Israel’s most prominent research institutions and is known for its pioneering work in physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics and computer science.

“In addition, they published leaked data to deepen fear. This is another example showing that enemies today do not differentiate between physical attacks and cyberattacks,” he added.

An outlet tied to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards disclosed in September that a Ministry of Intelligence documentary used archival images from the internet, despite presenting them as exclusive material obtained from Israel.

Intelligence Minister Esmail Khatib appeared in the program, calling the operation “a major infiltration” that yielded “a treasure of top-secret intelligence.” He described the outcome as the result of “months of complex planning and multiple successful operational phases inside the enemy’s structure.”

“On the last Yom Kippur, the attack on Shamir Medical Center was halted. At first it looked like classic ransomware. The Chilean ransomware group claimed they had stolen sensitive data. But after a short time, the ransom demand vanished because it became clear the real actor was Iran, using them as a front and trading on their tools,” Karadi continued. “It is a clear example of how some nation-states hide behind ransomware groups.”

Karadi said Israeli defenses prevented widespread damage, though he declined to give details or the full extent of the breaches.

A US cyber-security official attending the conference named Iran as among the most serious cyber threats to the United States.

“Russia, Iran, and North Korea are also major cyber threats, but China is the greatest,” Nick Andersen, executive assistant director for the Cybersecurity Division of the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), said.

“China is trying to use cyber weapons to pre-position the United States and the West for societal havoc and chaos in civilian infrastructure in the event of a conflict,” he added.

The US State Department on Tuesday denounced what it called the suspicious death of Iranian human rights lawyer Khosrow Alikordi, saying his case highlights the severe risks faced by those defending basic freedoms in the Islamic theocracy.

Alikordi, a 46-year-old prominent lawyer for jailed protesters and a former political prisoner, was found dead under unclear circumstances on Friday night, prompting some attorneys and activists to suggest possible Islamic Republic involvement.

"He devoted his life to defending Iranians who were fighting for freedom — including imprisoned protesters and the families of those killed by the Islamic Republic — even though he knew it meant putting his own life at risk," the State Department said in a post on its Persian-language X account.

"Years ago, he wrote: 'If I am killed, I am just one person — it is nothing. Do not let my homeland fall into the hands of the vile.' He never fought for himself alone; his struggle was for the people of Iran and for his country."

His death, the State Department said, "is a stark reminder of the dangers faced by those who fight for their rights in Iran."

"The United States continues to stand with the people of Iran in their pursuit of freedom and justice."

Alikordi died of cardiac arrest in his office in Mashhad, northeastern Iran, according to a report on Saturday by Iranian lawyers news agency (Vokala Press).

His body was transferred to the forensic institute for determination of “the main cause of cardiac arrest,” while police restricted entry to and from the office, according to media reports.

However, fellow lawyer Marzieh Mohebbi wrote on X that Alikordi died from “a blow to the head”, according to what she called "trusted contacts". Security officers, she said, removed cameras from the area and that access to his family had become impossible.

Alikordi, originally from Sabzevar and living in Mashhad, had represented political detainee Fatemeh Sepehri, several people arrested during the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom protests, and bereaved families including that of Abolfazl Adinezadeh, a teenager killed during protests.

“We find his death highly suspicious and do not believe he died of a heart attack," Adinezadeh's sister Marziyeh said in an Instagram post about their lawyer's death.

A dramatic cultural opening is sweeping across Iran, not as a government reform but as a bottom-up movement driven by a young generation that is less willing to be intimidated by the state, Iran analyst Omid Memarian told Eye for Iran.

Street concerts, outdoor festivals, late-night parties and music events have become increasingly visible in Tehran and beyond. Young people, many without the headscarves which are required for women, have filled pop and jazz concerts while street bands draw large crowds on central boulevards.

“This has nothing to do with the government,” Memarian said. “It is a very massive force underneath the society, and they are opening pathways that my generation was not able to even touch.”

Images and reports from across the country show men and women running together in a desert marathon in Kerman, while on Kish Island in the Persian Gulf the organizers of a separate marathon were arrested after women ran without hijabs.

Local media said more than 5,000 people took part in the Kish race, and photographs of female runners posing with medals and uncovered hair circulated widely online. Judicial officials accused organizers of “violating public decency” and said warnings about the dress code had been ignored.

The apparent cultural opening has been tolerated by authorities in its bid to shore up popular support in the wake of the punishing conflict with Israel and the United States, even as they have stepped up arrests and executions.

Memarian said the opening is not sudden. For years, multiple demographics “have been pushing inch by inch,” and many have paid a price. But two events accelerated it: the death of Mahsa Amini in morality police custody in 2022, which triggered nationwide protests and the twelve-day war between Iran and Israel earlier this year.

In June, Israel launched a surprise military campaign on Iranian nuclear facilities, missile production sites, killing nuclear scientists along with hundreds of military personnel and civilians.

Iran retaliated with waves of drones and ballistic missiles, prompting a week of exchanges. The United States then intervened directly, striking three Iranian nuclear sites at Fordow, Isfahan and Natanz with bunker-busting bombs.

Many Iranians spent nights sheltering in parking garages and stairwells. The government urged calm and vowed that its defenses had “full control,” yet many ordinary people said they felt unprotected.

“People were left alone. They saw the regime could not protect them. That created a huge vacuum and emboldened many Iranians,” Memarian said.

He emphasized that the changes are not limited to affluent parts of Tehran.

“It is a very widespread movement. From Tehran to small cities and villages, people are voicing their demands, imposing their lifestyle on the system.” Social media has erased the geographic divide, he added, allowing young people in remote areas to follow the same trends as their peers in urban centers.

“We have a massive explosion of expectations inside the country,” he said. “They are not going to let the government write their destiny. There’s no going back.”

Despite ongoing arrests and a rise in executions, officials have responded cautiously. The judiciary chief recently said the current relaxed approach to hijab enforcement “cannot continue,” and conservative voices have warned that “the Islamic revolution will soon disappear” if the trend continues.

Memarian said the state’s enforcement network sees the social shift as existential. “Those who favor repression are part of a massive, expensive machine,” he said. “Their identity, paycheck and power come from it. If they lose this, it’s over.” Some insiders, he added, now believe they cannot win. “They fear this is the beginning of the end. The domino has started to fall.”

Iran’s economy remains under strain, with sanctions, inflation, water shortages and energy problems. Yet Memarian said young Iranians remain focused on building their future ... one where the "Islamic Republic is something from the past.”

A former Iranian intelligence operative who collaborated with the US Central Intelligence Agency and transmitted secrets to journalists may have been killed by his own establishment stalwart father in 2016, The Atlantic reported.

While the presumed murder of Mohammad Hossein Tajik had been previously reported by Iranian dissidents, details published by the magazine's reporter Shane Harris with whom he corresponded provide new information about his motives and actions.

Harris wrote that he first made contact with Tajik after an Iranian hacker group called Parastoo posted its email address on a message board inviting people to make contact.

It had previously posted details about how a stealth US drone flying over Afghanistan had been commandeered and seized by Iran in December 2011.

The report cited Tajik as saying that his father, who goes by the honorific title Hajji Vali, had been a veteran agent of Tehran's security apparatus after storming the headquarters of the Shah's secret police amid the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

His family ties and facility with math and computers earned him a position at the intelligence ministry at age 18 and Tajik reportedly said he eventually came to lead an elite cyber-warfare unit.

Cyberattacks

Harris said Tajik told him Iran focused its operations on Israel and Saudi Arabia, adding that he had played a role in a 2012 cyberattack on the Saudi state oil company Aramco in which information was wiped from three-quarters of its office computers.

Tehran, Tajik said, had shared techniques with Russia's GRU intelligence service and had attacked the electrical grid of NATO member Turkey in 2015.

Iran had also played a secret role, he went on to allege, in a February 2016 attack on the central bank of Bangladesh in which $81 million was stolen, for which the United States later indicted three North Korean hackers.

Tajik alleged that Tehran had instructed its Lebanese ally Hezbollah on how to penetrate the SWIFT international banking network and the group had passed the information on to Pyongyang in exchange for missiles.

Torture, death

For reasons which remain unclear, Tajik began collaborating with the CIA around times in which the agency scored major intelligence success against Iran and its allies, Harris reported.

His relationship coincided with the assassination of veteran Hezbollah military chief Imad Mughniyeh in Damascus in a joint US-Israeli operation in February 2008 and the discovery of Iran's secret underground uranium enrichment facility Fordow in September 2009.

Tajik did not take credit for either, Harris reported. Fordow was among three Iranian nuclear sites bombed by the United States on June 22.

The CIA, Tajik told Harris, had declined to work with him further but had said it would extract him from the country should he wish. But Tajik said he either wanted to rekindle his relationship with the agency or he would expose their secrets on Iran.

Tajik expressed strong dissatisfaction with Iran's ruling system in their conversations.

US intelligence ultimately severed the relationship. "The CIA had cut ties because the risk of working with him became greater than the value of his information," Harris wrote. "My sources told me he didn’t follow instructions. One day he’d be clearheaded; the next he’d be acting paranoid, imagining conspiracies."

"Some officers wondered if he was taking drugs that impaired his judgment. It’s a handler’s job to manage sources," he added. "And Mohammad, one US official told me, had become 'unmanageable.'"

Tajik had departed from the agency's protocols by using a personal phone to take pictures of communications on his CIA-issued laptop. Authorities arrested him and by September 2013 he was transferred to Tehran's Evin Prison where he was tortured by having boiling water poured on his penis and being forced to lie in a grave-like hole.

“Being still a double—turning into a triple and later to a nothing/everything/ticking-bomb," the report quoted Tajik as confiding, in a possible indication that his bid to get reconnected to the CIA via the journalist was forced by his interrogators as a condition of his freedom.

Harris reported that Tajik had introduced him a month before his death to Ruhollah Zam, an Iranian dissident journalist living in Paris. Zam told him that Tajik was murdered on July 5, 2016, in his home by his father in a move to preserve family honor as his son was preparing to leave the country.

His death records on Tehran's Behesht-e Zahra cemetery website says he died on July 7.

According to the Atlantic report, Tajik received no autopsy nor did his death certificate list a cause of death.

Friends cited by Harris said he had become addicted to painkillers after his torture, but that the cause of his death was never confirmed. He was 35 years old when he was murdered.

Zam was lured to Iraq with the promise of an interview with a senior cleric only to be abducted by Iranian agents and hanged in Tehran in 2020.