Araghchi meets IAEA chief ahead of second round of Iran-US talks

The head of the International Atomic Energy Agency met Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi in Geneva on Monday, state media reported, a day before a second round of talks between Iran and the United States.

The first round of Iran-US negotiations was held earlier this month in Muscat, mediated by Oman. Tuesday’s talks are also set to take place at Oman’s embassy in Switzerland.

Iranian media described the meeting with the IAEA chief as part of preparations for the next phase of negotiations. Foreign ministry spokesman Esmaeil Baghaei said talks were moving forward within frameworks approved by senior state bodies and stressed that Iran was negotiating “in a climate of complete mistrust.”

Baghaei said Iran’s position was “completely clear,” adding that as a committed member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Iran accepted both its obligations and its rights. “Our right under Article 4 of the treaty is the peaceful use of nuclear energy, and enrichment is part of that,” he said.

He added that issues such as “what level of enrichment, to what extent, and how many centrifuges we will have” had not yet been discussed in detail. Baghaei also said different branches of the system had reviewed the negotiations and reached a unified decision to use available capacities, including at the foreign ministry and the Supreme National Security Council, to advance the talks.

Israeli prosecutors have charged a man with gathering intelligence on former defense minister Yoav Gallant on behalf of an Iranian agent.

According to the indictment, Fares Abu al-Hija was arrested in late January after photographing streets near Gallant’s home in Amikam at the direction of his handler. Police and the Shin Bet security service said he is from the Galilee village of Kaukab Abu al-Hija.

Prosecutors said he first made contact with the alleged Iranian agent on Telegram while searching for work and was paid in cryptocurrency for carrying out intelligence-gathering missions. Before surveilling Gallant’s residence, he was allegedly instructed to film a cafe in Tel Aviv, earning $1,000 in digital currency.

He has been indicted on charges of contact with a foreign agent, and prosecutors are seeking his detention until the end of proceedings.

Iran’s Judiciary Chief Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei said authorities should not delay issuing indictments against what he described as the “main protesters” involved in the unrest, adding that the public expected trials and punishment.

“We must not delay in issuing indictments related to the main elements of the disturbances,” Ejei said, according to state media. He added that investigations may take longer in some cases because of the “multi-layered” nature of the alleged actions.

Rights groups say tens of thousands of protesters have been arrested during the uprising, with detentions continuing.

Iran’s clerical leadership only understands strength, US Senator John Hoeven said, arguing that a US show of force was meant to signal to Iran’s leaders “that this is serious and that change has to happen.”

“There's only one thing that the Ayatollahs in Iran understand, and that's strength. And in the Middle East, there's an old saying, bet on the strong horse. And President Trump and the United States are the strong horse,” the North Dakota Republican told Fox News.

Hoeven described Iran’s ruling system as “the largest exporter of terrorism in the world” that oppresses Iranians and supports groups such as Hamas, Hezbollah and the Houthis.

“This is the kind of oppressive regime that the people of Iran are suffering under right now,” he said, referring to marches on Saturday, when hundreds of thousands of Iranians took to the streets against Iran’s government across the world.

Hoeven also talked about the role exiled Prince Reza Pahlavi plays and added that “Ultimately, it's got to be about what the Iranian people want for their governance.”

Iran’s oil exports declined sharply at the start of 2026, new tanker-tracking data show, raising fresh questions about the durability of Tehran’s most important economic lifeline under renewed US sanctions pressure.

Crude oil loadings from Iran’s Persian Gulf terminals fell to below 1.39 million barrels per day in January, a 26 percent drop from a year earlier, according to data from commodity intelligence firm Kpler reviewed by Iran International.

The decline extends a steady downward trend since October, suggesting sustained pressure rather than a temporary disruption.

The slowdown is most visible in China, Iran’s primary—and effectively only—major oil buyer under sanctions. Daily discharges of Iranian crude at Chinese ports fell to 1.13 million barrels per day last month, down from an average of around 1.4 million barrels per day in 2025.

Unsold Iranian crude is also accumulating at sea. The volume of oil stored on tankers has nearly tripled over the past year to more than 170 million barrels, a sign that shipments are becoming harder to sell or deliver.

Keeping that oil afloat is costly. Chartering a Very Large Crude Carrier typically costs more than $100,000 per day, and tankers carrying sanctioned Iranian oil command even higher rates due to legal and insurance risks. Analysts estimate that roughly one-fifth of Iran’s oil revenue is effectively consumed by these transport and storage costs.

Much of the oil remains stranded in Asian waters. About one-third of Iranian tankers are anchored offshore, while others move continuously or conduct ship-to-ship transfers to evade sanctions enforcement—tactics that have become standard within Iran’s so-called shadow fleet.

Sanctions are increasingly targeting those networks. According to Kpler, 86 percent of the tankers transporting Iranian oil over the past year have themselves been sanctioned by the United States, highlighting the expanding scope of enforcement.

The pressure has forced Iran to offer steep discounts to maintain sales. Iranian crude is currently priced about $11 to $12 per barrel below comparable benchmarks, up from a discount of roughly $3 per barrel early last year, significantly reducing Tehran’s net income.

The decline extends beyond crude oil. Exports of petroleum products such as fuel oil fell to about 350,000 barrels per day in January, down from 410,000 barrels per day a year earlier, with China and the United Arab Emirates among the main buyers.

Additional pressure may be coming. President Donald Trump recently signed an executive order imposing a 25 percent tariff on trade partners of Iran, a measure that could further deter companies and countries from handling Iranian oil.

The mounting economic strain provides important context for renewed indirect talks between Washington and Tehran.

For Iran’s leadership, easing sanctions remains the most direct path to stabilizing oil revenues and relieving fiscal pressure. But deep differences over Iran’s nuclear program, missile development, and regional activities make an agreement unlikely unless one side decides to compromise on core demands.

Taken together, the data suggest that Iran’s ability to sustain oil exports under sanctions—long a cornerstone of its economic resilience—is becoming more constrained.

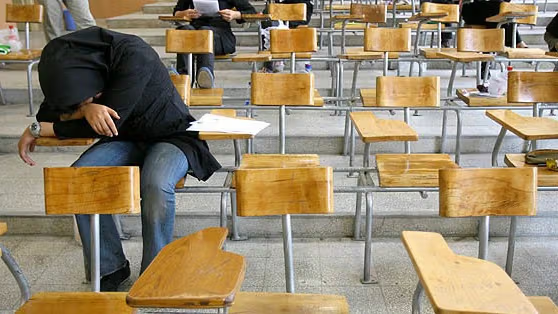

A tightening security atmosphere inside schools across several Iranian cities has prompted a new wave of student absences, according to messages sent to Iran International, with families saying classrooms no longer feel like safe spaces for their children.

In recent weeks, parents and students from Mashhad, Gorgan, Tehran and other cities across Iran have described schools shifting from educational environments to spaces marked by heightened monitoring and questioning.

A student in the religious city of Mashhad said school officials and affiliated forces had searched students’ mobile phones and, in some cases, searched schoolbags.

After this started, a few of my classmates stopped coming to school, the student added.

Similar accounts have emerged from girls’ schools in Gorgan, northern Iran. Several students told Iran International that inspections were accompanied by what they described as an atmosphere of intimidation, leading some families to temporarily withdraw their children from classes.

Rising absenteeism amid safety fears

No official figures have been released on attendance rates, but interviews with teachers in Tehran and Alborz province suggest that classroom numbers have dropped in some schools.

“In a class of 25, some days fewer than half are present,” a high school teacher in Tehran said, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue. “Parents say they do not consider the situation safe.”

A mother of an eighth-grade student in eastern Tehran said she had allowed her child to stay home for several days. “School should be the safest place for a child,” she said. “When I hear about inspections and questioning, it is natural to hesitate.”

The latest reports follow earlier accounts of security forces and Basij members entering schools in cities including Abadan in the south, Arak and parts of Mazandaran province, north of Iran.

Families previously reported that students were asked to sign written pledges without their parents present. In Bandar Abbas, Malayer and Gorgan, students were questioned about their families and protest-related activities. In Arak and Sari, some educational facilities were said to have been used as bases for security forces.

‘Deep rupture' between families and schools

Saba Alaleh, a Paris-based clinical psychologist and socio-political psychoanalyst, told Iran International that the developments point to a structural break in trust.

“We are witnessing a profound psychological and social rupture between families and schools,” she said.

“This rupture is not limited to recent events; it is the result of years of accumulated distrust.”

Experiences during the Woman, Life, Freedom protests in 2022, when schools were described as spaces of fear and pressure, intensified that mistrust, Alaleh said.

“A school should provide a sense of security. When it becomes associated with surveillance and threat, it transforms into a source of anxiety,” she added.

She warned that exposure to inspections and questioning could have lasting consequences for children. “When students experience constant monitoring, education can lose its meaning,” she argued.

“This can lead to declining motivation, deeper distrust and even identity confusion.”

Healthy psychological development, Alaleh explained, depends on a functional partnership between family and school.

“When that bond collapses, children may find themselves caught between conflicting value systems, complicating their social and identity development,” she added.

Long-term consequences for education

Nahid Hosseini, a London-based researcher on women’s affairs and education, said the recent developments reflect a broader crisis within the education system.

“When an educational environment is perceived as unsafe, it is natural for parents to withhold their children,” she told Iran International. “But the result is the deprivation of millions of students from their right to education.”

With Iran’s student population estimated at more than 15 million, Hosseini said sustained absenteeism and declining trust in schools could have far-reaching social and economic consequences.

“Schools should be spaces of stability and growth. When they become associated with fear, the cost is borne not only by students but by society as a whole.”

A sanctuary no longer certain

For many families, the issue is no longer limited to temporary absences but to a broader shift in how they view the institution of schooling.

“In the past, even if there were problems, we still believed school was fundamentally safe,” a mother in Tehran said. “Now I feel my child is under pressure there.”

In the absence of transparent communication about the scope and purpose of security measures inside schools, distrust appears to be widening.

Experts warn that once a school loses its standing as a safe haven, rebuilding that trust may prove far more difficult – with implications that could shape a generation’s relationship with formal education for years to come.