The detentions, which have targeted senior members of the Reform Front of Iran and figures associated with President Masoud Pezeshkian, come as the Islamic Republic remains shaken by the deadliest crackdown in its history.

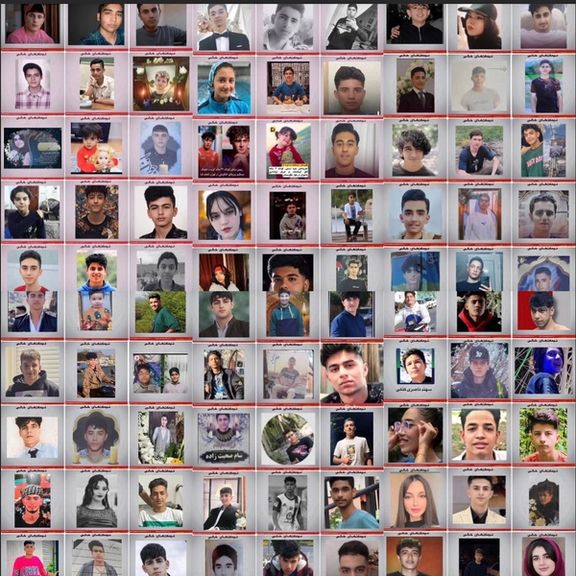

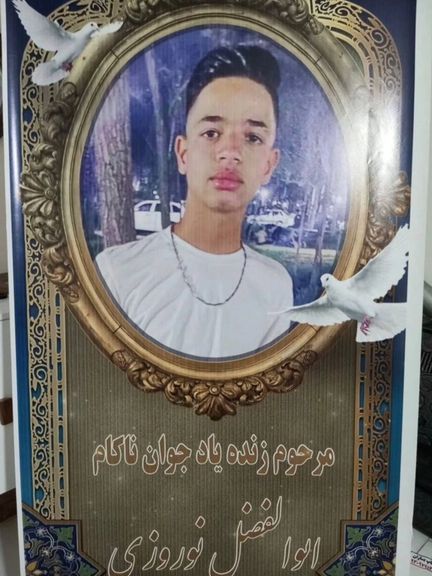

The protests, which gained momentum after a call by exiled Prince Reza Pahlavi, were crushed by the Islamic Republic’s live fire, leading to the massacre of at least 36,500 people.

The arrests also come at a time when Tehran’s theocracy is deeply uncertain about the trajectory of diplomacy with Washington.

Officials have framed the arrests as a response to “coordination with enemy propaganda” and efforts to undermine national cohesion—language that signals heightened sensitivity to any challenge to the state’s narrative at a time of external pressure.

With talks with the United States back on track, Iran’s leadership appears intent on closing ranks at home, moving to eliminate deviations from the official line, particularly among figures who until recently were tolerated as part of a tightly managed political spectrum.

Public statements by judicial and security bodies have offered little ambiguity. Those detained have been accused of promoting “surrenderism” toward the United States and acting in the interests of Israel.

The hardline daily Kayhan, whose editor is appointed by the supreme leader, described those arrested as extremists who had aligned themselves with “overthrowists,” effectively placing even moderate critics beyond the pale.

The detainees

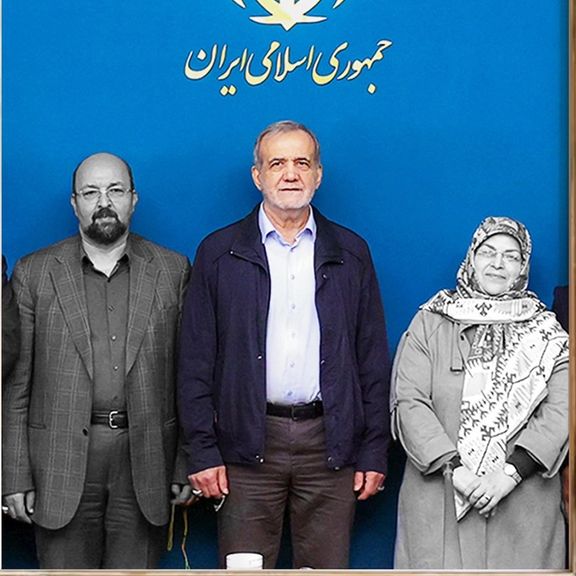

Those detained include senior figures from the Reform Front and its largest constituent party, the Union of Islamic Iran People Party. Among them are Azar Mansouri, head of the Reform Front; Javad Emam, its spokesman; former diplomat Mohsen Aminzadeh; and the veteran politician Ebrahim , the leader of radical students who stormed the US embassy in 1980.

One case appears to reflect a clearer red line.

An audio recording that circulated online captured remarks by Ali Shakouri-Rad, a senior party figure, who rejected the official account of the recent protests and accused security forces of manufacturing violence.

“Security institutions in Iran, in every protest, have injected violence to use it as a pretext for repression,” he said. “It has been like this from the beginning, and it has gotten worse day by day.”

Yet for much of Iranian society—still grieving the mass killing of protesters in January—this confrontation within the political elite has the feel of an argument unfolding in a parallel universe.

The protests, which began over economic hardship and rapidly escalated into nationwide calls for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic, were met with overwhelming force. Tens of thousands were killed in a matter of days, according to internal assessments reviewed by Iran International.

In the aftermath, Pezeshkian and the moderate camp from which he emerged broadly aligned themselves with the state’s narrative, avoiding public confrontation with the security establishment.

That alignment proved decisive. For many Iranians, Pezeshkian’s election in 2024 represented a final, tentative wager on incremental change from within the system. His conduct during and after the crackdown extinguished that hope.

Against that backdrop, the latest arrests appear less a dramatic rupture than a belated narrowing of a political space that had already collapsed in the public mind.

The exception lies with a small group of activists who crossed a line the system still treats as inviolable. Several of those detained were linked to a January 2 statement signed by 17 political and civil figures declaring the Islamic Republic illegitimate and calling for a peaceful transition of power.

Unlike most reformist figures, the signatories explicitly rejected the framework of the existing order, underscoring where the authorities continue to draw their true red lines.

Figures associated with the 2009 Green Movement have also been swept up, including advisers and relatives of its leaders, Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi. Mousavi, under house arrest for more than a decade, recently described the killing of protesters as a “black page in Iran’s history” and called on leaders to step aside.

As negotiations with the United States resume amid warnings of war, the leadership is signaling that internal discipline will take precedence over political pluralism — even of the carefully managed kind once associated with reformism.

For most Iranians outside the corridors of power, however, the arrests change little. Few still see themselves reflected in the state’s internal disputes.