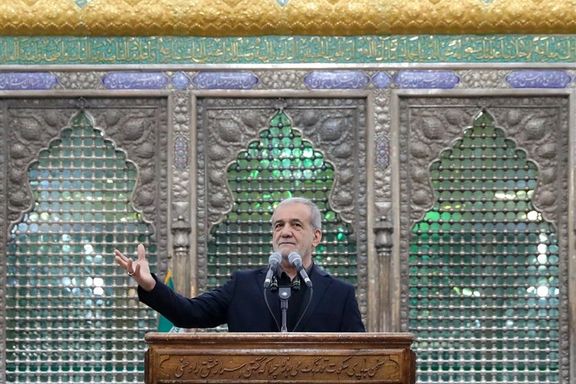

Speaking in Istanbul on Friday, Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said Iran would consider US proposals for negotiations only if the military threat was removed first. Araghchi was in the Turkish city to explore a possible mediation initiative, though he made clear that Tehran would not negotiate under pressure.

Hours later, US President Donald Trump said he had directly communicated a deadline to Iran for reaching an agreement with Washington. “Only they know about the deadline for sure,” Trump told reporters, without elaborating on the terms or consequences.

The exchange reflects a familiar standoff: Washington is attempting to force rapid movement at a moment when Iran is politically and economically weakened, while Tehran is signaling defiance even as it quietly probes diplomatic off-ramps.

Ahmad Bakhshayesh Ardestani, a member of parliament’s Foreign Policy Committee, said on Thursday that internal debates were under way in Tehran over how far Trump might go.

“Trump’s confrontation with Iran during his first term was a failure,” he told news website Didban Iran, setting out his assessment that the US president’s long-term aim was to end the Islamic Republic.

“He knows there is no third term, and this is his only chance.”

Ardestani also argued that regional powers including the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Turkey oppose the collapse of the Islamic Republic, which he said they view as destabilizing and economically disruptive.

Former Iranian diplomat Kourosh Ahmadi offered a more cautious assessment.

Speaking to Entekhab on January 29, he said Trump’s deployment of military forces was intended primarily to intensify diplomatic and economic pressure on Tehran rather than signal a settled decision to strike.

“Trump does not want to be remembered as a president who failed to deliver on his promises,” Ahmadi said, adding that the show of force was designed to deepen Iran’s economic crisis and force concessions.

Araghchi has denied that talks are planned with US envoy and Trump aide Steve Witkoff, even as he travels regionally to discuss mediation proposals.

Ahmadi said US military action remained possible but warned that Trump would face difficulties justifying an attack both internationally and to his domestic political base.

He also dismissed speculation that Washington might attempt to block Iran’s oil exports, arguing that such a move would almost certainly trigger military confrontation in the Persian Gulf and affect China and Arab nations in the region.

Ironically, Iran’s hardline daily Kayhan—close to the office of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei—has suggested that Tehran itself should consider closing the strategic waterway.

Rahman Gharemanpour, an international relations expert, told Donya-ye Eghtesad that preparations for a major operation would require significantly more time and should not be read as evidence of an imminent attack.

In the same newspaper, Mashhad University academic Rouhollah Eslami said regional states are increasingly guided by cost-benefit calculations rather than ideological alignment—a shift that helps explain their reluctance to support military action against Iran.

For now, Iran’s position remains deliberately unresolved. Araghchi insists Tehran is prepared both for negotiations and for war—and given the balance of fear and defiance now shaping decision-making in Tehran, he may not be spinning for once.