Why did Iran ban the Saudi Ramadan TV series?

Iran’s media regulator (SATRA) has joined Iraq and scholars from Egypt’s Al-Azhar in banning Muawiya, a Ramadan TV series aired by Saudi Arabia’s MBC channel.

Iran International

Iran’s media regulator (SATRA) has joined Iraq and scholars from Egypt’s Al-Azhar in banning Muawiya, a Ramadan TV series aired by Saudi Arabia’s MBC channel.

On Wednesday, the Iranian Audio-Visual Media Regulatory Authority (SATRA) announced a ban on dubbing and streaming the controversial series across all video-on-demand platforms, private websites, and social media channels.

The regulatory authority, which operates under the country's sole radio and television program provider, the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), stated that the series was unfit for streaming because it “attempts to absolve the Umayyad Dynasty [of wrongdoing against Shia saints]”.

Muawiya: A controversial historical drama

MBC began airing Muawiya—widely regarded as the most expensive series ever produced in the Arab world—a few days ago.

Although completed in 2023, its release was postponed until now due to anticipated controversies.

The historical drama focuses on the life of Muawiya, recognized as the first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, an early Islamic empire. His reign began after the Prophet’s son-in-law Ali was assassinated in 661 AD, an event that profoundly impacted the political and religious landscape of the Muslim world.

Iranians’ interest in the series

Many Iranians on social media expressed curiosity about the historical perspective presented in the series, which is expected to contrast sharply with Shia teachings.

MBC, a free-to-air satellite channel, is accessible to many Iranians, but the series is in classical Arabic.

After Persian-subtitled episodes surfaced online in recent days, SATRA intervened and later announced that these were removed in collaboration with judicial authorities.

Iran's alternative programming

On Sunday, the first day of Ramadan in Iran, state-run television resumed broadcasting its own Imam Ali series.

Originally produced in 1997 and considered one of IRIB’s most expensive productions, it follows Shia tradition by depicting the later years of the third caliph, Uthman, and his successor, Ali.

Ali, the Prophet Muhammad’s cousin and one of the earliest converts to Islam, later married the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima. He is regarded as the first of the 12 Shia saints.

Ban in Shia-majority Iraq

Iraq’s media regulator banned the 30-episode series last week, citing concerns that it could incite Shia-Sunni tensions.

While the show has been removed from MBC Iraq, it remains available on other MBC channels and digital platforms.

Why do Shia consider Muawiya a usurper?

The Umayyad rule (661-750 CE) that followed Ali's assassination marks the beginning of the Shia-Sunni divide and dynastic rule in Islamic history.

Then governor of Syria, Muawiya opposed Ali’s election as the fourth and final Rashidun caliph and waged war against him in 657 AD. The Battle of Siffin ended in arbitration, with neither side achieving a decisive victory.

Following Ali’s assassination, Muawiya also challenged the leadership of Ali’s son, Hasan. According to Shia tradition, Hasan agreed to renounce his claim to leadership of Muslims to avoid bloodshed. Shia beliefs hold that Muawiya later poisoned Hasan. Muawiya’s son, Yazid, subsequently defeated and killed Hasan’s younger brother, Husayn, in the Battle of Karbala in 680 AD, a pivotal event in Shia history mourned by millions in Iran and Iraq on its annivesary.

Egyptian Al Azhar scholar’s condemnation

Senior Islamic scholars at Egypt’s Al Azhar University have also prohibited viewing the show, albeit for reasons differing from those in Iran and Iraq.

According to Arab media, their opposition is based on the broader Sunni principle that the Prophet Muhammad’s family and companions, including the four caliphs, should not be depicted in films.

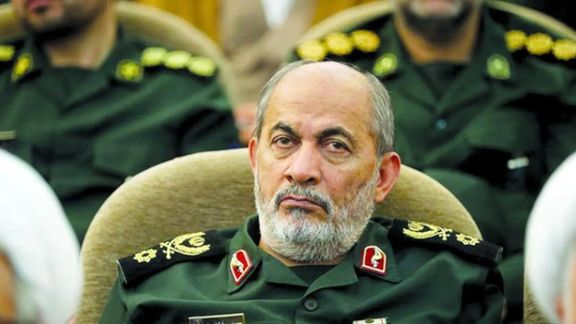

Iran’s first minister of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) admitted to overseeing assassinations of opposition figures abroad, revealing new details about Tehran's decades-long campaign of targeted killings.

In an interview with the Tehran-based news website Didban Iran, Mohsen Rafiqdoust said he personally oversaw operations against exiled dissidents, including former Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar, military officials Gholam-Ali Oveissi and Shahriar Shafiq, and dissident artist Fereydoun Farrokhzad.

“The Basque separatist group in Spain carried out these assassinations for us. We paid them, and they conducted the killings on our behalf,” Rafiqdoust said.

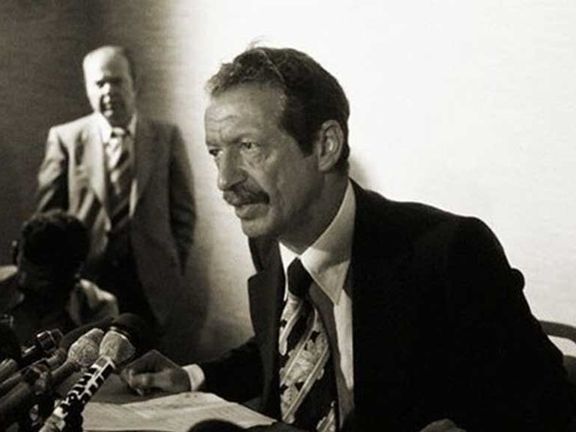

He recounted his role in the 1991 assassination of Bakhtiar in Paris, saying he supervised Anis Naccache, a Lebanese operative who had previously attempted to kill Bakhtiar in 1980 but failed.

According to Rafiqdoust, he traveled to France to negotiate Naccache’s release, warning French officials: “If after two weeks he is not freed and one of your embassies is bombed or a plane hijacked, don’t complain.”

Naccache himself had previously said in a 2008 interview with the IRGC-affiliated Fars News Agency that Iran’s then Leader Ruhollah Khomeini personally approved the order to kill Bakhtiar.

“The Islamic Revolutionary Court issued his death sentence, and Khomeini endorsed it. I told the IRGC members that I had operational experience and would carry it out,” Naccache said.

The Iranian government has been implicated in multiple assassinations over the past four decades. In 1984, the Chief Commander of the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces Gholam-Ali Oveissi and his brother were shot dead in Paris.

The Lebanese group Islamic Jihad, later linked to Hezbollah, claimed responsibility for the attack. The group’s leader, Imad Mughniyeh, played a role in several international terrorist operations, including the 1983 bombing of the US Embassy in Beirut and attacks against Israeli targets in Argentina.

Iran’s campaign of assassinations began in 1979 with the killing of Iranian Imperial Navy Captain Shahriar Shafiq in Paris and has continued for decades.

A report published in December by the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center documented 862 extrajudicial executions and 124 attempted kidnappings or assassinations by the Iranian state.

The campaign has escalated in recent years. A Reuters investigation in 2024, citing court documents and statements from Western governments, reported that Iran had been involved in at least 33 assassination or kidnapping attempts since 2020.

Iran’s reach has extended to the United States. Washington has accused Tehran of orchestrating at least five assassination plots on American soil since 2020.

Journalist and activist Masih Alinejad was among those targeted, with US authorities uncovering Iranian-backed attempts to kill her through hired operatives.

In one of the most high-profile cases, Iranian security forces abducted journalist Ruhollah Zam in Iraq and transferred him to Iran, where he was executed in 2020.

Similarly, dissident Jamshid Sharmahd was kidnapped in the UAE and later executed in Iran in 2024.

Iran’s targets have not been limited to its own dissidents. The US Department of Justice recently disclosed details of an Iranian plot to assassinate President Donald Trump before the 2024 election.

A federal indictment in Manhattan named Farhad Shakari, a 51-year-old Iranian national, as the lead operative, along with two American accomplices.

The US government has long designated Iran as a leading state sponsor of terrorism, imposing extensive sanctions in response to its activities.

It is not only Iranian dissidents that have been the targets of Iranian plots. The head of Israel's Mossad, David Barnea, said in 2023 that in the last year, there had been 27 plots foiled targeting Israelis in Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America.

In Israel alone during 2024, Iran-backed plots soared by 400% with 13 cases and 27 Israelis indicted.

The Director General of the UK's MI5 also recently stated that since the start of 2022 the UK has responded to 20 Iran-backed plots, presenting potentially lethal threats to British citizens and UK residents, directly blaming the IRGC.

"The Iranian Intelligence Services, which include the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the IRGC, and the Ministry of Intelligence and Security, or MOIS, direct this damaging activity," a statement earlier this month said.

"But often, rather than working directly on UK shores, they use criminal proxies to do their bidding. This helps to obfuscate their involvement, while they sit safely ensconced in Tehran."

MI5 said that Iran is targeting dissidents, media organizations and journalists reporting on the government's "violent oppression".

It also acknowledged the danger posed to Jews and Israelis abroad.

"It is also no secret that there is a long-standing pattern of targeting Jewish and Israeli people internationally by the Iranian Intelligence Services," added the statement. It is clear that these plots are a conscious strategy of the Iranian regime to stifle criticism through intimidation and fear."

On March 8, 1979, tens of thousands of Iranian women took to the streets, demanding the right to choose what to wear on the first International Women’s Day of the post-revolutionary Iran.

The rally that was supposed to be a celebration of women, became the start of a six-day battle against the newly imposed Islamic dress code on them. It was perhaps the earliest sign that the revolution they had fought for had been hijacked.

Only weeks before, many of these same women—students, doctors, lawyers, nurses, teachers, activists—had marched against the dictatorial rule of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, fighting for freedom, democracy, and equality, unaware that they would become the first victims of Iran’s Islamization led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

On March 7, 1979, Khomeini decreed that all women working in government offices must heed Islamic diktats and cover their hair. The following day, women arriving at work unveiled were turned away.

Many felt this was not about clothes, but control. They saw it as an attempt to erase women from public life. And they fought back.

“We did not rise to go back,” thousands chanted marching from the University of Tehran toward the Prime Minister’s office. “In the dawn of freedom, women’s rights are missing.”

The peaceful demonstration was met with brute force. Islamist revolutionaries and pro-Khomeini mobs stormed the march with sticks and knives. Dissenting women were beaten and stabbed. They were called enemies of Islam and agents of the West.

But they did not back down.

For six days, they marched through the streets of Tehran, defying the cold, the growing danger, and the bitter sneering of those who dismissed their struggle as secondary to the revolutionary cause.

The dismissive view was by no means limited to Iranian masses. It was shared by many Western intellectuals who, bewitched by the revolution in Iran, ignored or actively justified the repression of the new regime.

Thinkers afar: enablers and allies

While feminists like French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir and American writer Kate Millett stood in solidarity with women in Iran, others like de Beauvoir’s compatriot Michel Foucault helped legitimize the Islamic Republic.

De Beauvoir recognized the Iranian women’s fight as part of the global struggle for gender equality, helping establish the International Committee for Women’s Rights (CIDF) to amplify their voices. Millett traveled to Iran to document their struggle and was arrested and expelled for her efforts.

Foucault also visited Iran but had a wholly different view of the events. He romanticized the revolution, reducing it to a rejection of Western imperialism and ignoring its catastrophic consequences for women and dissidents. He brushed aside human rights concerns as Western biases, a framing that persists in various forms to this date.

Another lasting influence in Western intellectual circles is Palestinian-American philosopher and literary critic Edward Said.

Said’s most influential work, Orientalism, was published a year before the revolution in Iran. He focused on Western narratives about the East. While many of his arguments against colonialism were valid, they were weaponized by Islamists to deflect criticism.

Said, unlike Foucault, never glorified Iran’s transformation. Others used his emphasis on culture, however, to depict forced veiling and gender segregation as cultural differences rather than human rights violations, failing to—or choosing not to— challenge the repression in a meaningful way.

A Legacy of Resistance

Back in Iran, the forced veiling of women was completed and codified in 1983. Those daring to flout the law would be punished by official enforcers or emboldened thugs. The Six-Day Protest of 1979 was defeated.

But it heralded a long fight for equality that’s continued to this date.

In 2022, the world watched as Iranians across Iran took to the streets after a 22-year-old Kurdish woman named Mahsa Amini died in custody, having been detained for not covering her hair fully.

Amini’s tragic death—a state murder by all accounts—ignited the largest uprising against the Islamic Republic. Young men tore down posters of supreme leader Ali Khamenei as young women set their scarves on fire.

Their slogan? “Woman, Life, Freedom.”

The struggle against hijab and gender apartheid is not just an Iranian issue—it is a global human rights fight. Iranian and Afghan women continue to resist, even as the Islamic Republic and the Taliban impose laws aimed at erasing them from public life.

What happened on March 8, 1979, is not just history, it is a warning. Revisiting that eventful day and what has happened in Iran since, may help Western intellectuals and politicians see mandatory hijab for what it is: systemic, religious oppression, not a symbol of cultural relativism.

When enforced by law, hijab is not a cultural practice. It is a means of control. Iranian and Afghan women are calling for solidarity, demanding that the world listen to them rather than the Foucaults of the world.

International Women’s Day is a day to honor those who fought and are fighting for equality. It also has to be a day to reject the view that dismisses their struggle, and enables their oppressors.

Opinion expressed by the author are not necessarily the views of Iran International.

The Islamic Republic will not engage in negotiations with "bullying" powers, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said in a speech on Saturday, a day after US President Donald Trump sent him a letter requesting nuclear talks.

Khamenei's official website quoted him as saying, "The insistence of some bullying governments on negotiations is not aimed at resolving issues but rather at asserting dominance and imposing their own demands. The Islamic Republic of Iran will certainly not accept their expectations."

President Trump revealed on Friday that he had sent a letter to Khamenei, offering negotiations while warning of military consequences if talks failed. Speaking to Fox Business Network, Trump said, “There are two ways Iran can be handled: militarily or through a deal. I would prefer to make a deal.”

Many in Iran anticipated Khamenei’s response to President Donald Trump’s letter during his speech at a meeting with top government officials on Saturday afternoon. Although the full text of his speech has not yet been released, but apparently he did not directly address Trump's letter.

Khamenei routinely meets with senior government officials, including the president, every Ramadan. This time, however, the announcement came unusually late on Friday evening Tehran time. This followed Trump’s revelation that he had sent Khamenei a letter offering negotiations on Iran's nuclear program while warning that military intervention was the alternative.

Iran has not officially acknowledged receiving Trump’s letter. On Friday, Tehran’s UN mission in New York stated that Iran had “so far” not received any such correspondence.

Speculation over Russian mediation

Highlighting the mediatory role that Russia is playing between Iran and the US, some Iranian media and pundits have speculated that the letter may have been handed to the Iranian ambassador Kazem Jalali during his meeting with the Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov around midday Tehran time on Friday. Tehran and Moscow both said the meeting was to discuss international efforts to resolve Iran's nuclear program and Tehran-Moscow cooperation.

Hardline media predict no response

Trump sent another letter to Khamenei in 2019, after unilaterally withdrawing from the 2015 nuclear deal. Khamenei refused to accept the letter, delivered by then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, and insisted that Trump was untrustworthy.

An editorial in the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) linked Javan newspaper on Saturday dismissed Trump’s latest letter as “a segment of America’s propaganda puzzle”. Referring to Khamenei’s refusal to accept Trump’s 2019 letter, the editorial suggested that Iran would once again ignore Trump’s message. “Based on the Islamic Republic’s polices; one can predict Iran's response to the letter. There will be no reply, assuming the letter is allowed to be delivered,” the article stated.

The ultra-hardliner Kayhan newspaper similarly referenced the 2019 incident and Khamenei’s rejection of the idea of negotiations with the United States in a speech in February. In its editorial on Saturday, Kayhan argued that Trump’s primary goals was to improve his own image and shift blame for lack of diplomacy onto Iran.

Backchannel diplomacy

Iran and the United States typically communicate through backchannels or intermediaries, such as Oman, which has on several occasions facilitated meetings between officials of the two countries or relayed messages.

Former President Barack Obama reportedly sent multiple letters to Khamenei between 2009 and 2015, discussing topics such as diplomacy, the nuclear deal (JCPOA), and potential cooperation against ISIS. However, there are no reports that Khamenei ever responded in writing to any of these letters.

The ceasefire between Turkey and an outlawed Kurdish group could further empower Ankara to fill a regional power vacuum after Tehran and its allies were battered in warfare with Israel, foreign relations expert Henri Barkey told Eye for Iran.

“Iran is very alone at the moment” said Barkey, an adjunct senior fellow for Middle East studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington DC.

The push for a resolution to a decades-old insurgency by the Kurdish Workers Party against the Turkish state comes as the Middle East's tectonic plates shift and global alliances are in flux as President Donald Trump cast upends US commitments.

"We have a completely changed strategic situation in the Middle East," said Barkey, "no one at the moment has any dominance in the Middle East and it's up for grabs."

"Iran, for the foreseeable will not be able to do what it used to do in the past," added Barkey.

After 15-months of direct combat and proxy warfare pitting Iran against Israel throughout the region, Tehran has come off worse.

It's main ally Hezbollah in Lebanon took a heavy toll from an Israeli ground invasion and air strikes. Most notably, Iran's oldest ally in Syria's Assad dynasty was toppled by Sunni Islamist rebels closer to Turkey, giving Ankara a new regional ward.

How Turkey benefits from peace with the PKK

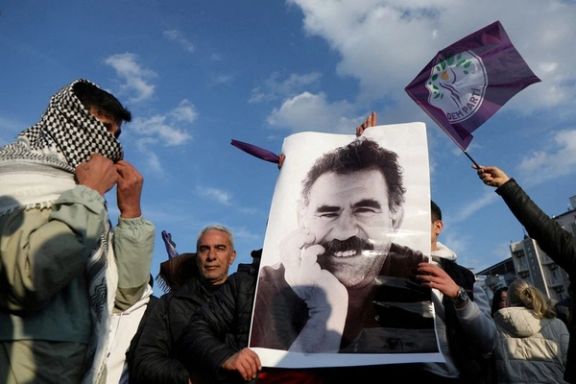

The jailed leader of the PKK Abdullah Ocalan called on its members to lay down arms in an address from his island prison near Istanbul on Feb. 27.

That announcement was followed by a ceasefire days later which ended 40 years of armed struggle for a Kurdish homeland.

While President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's rapprochement is largely driven by domestic political considerations to create a new constitution enabling him to run for a third presidential term in 2028, Turkey stands to likely make gains in Northern Iraq, where many PKK fighters are stationed.

Turkey’s gains may be Iran’s losses.

“Both Turkey and Iran would like to influence Iraqi Kurds,” said Barkey.

The Turks and PKK making peace formally will help in those efforts to increase influence.

The relationship between Turkey and Iran Barkey characterized as complex, but one in which there are at least cordial ties and a stable border. Both Islamic nations, however, are revisionist with ideals of grandeur.

Turkey's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hakan Fidan, said in an interview with Al Jazeera Arabic last month that Iran's foreign policy of relying on militias led to more losses than gains.

Shifting tectonic plates

Recent diplomatic tensions between Tehran and Ankara represents a broader shift in the Middle East.

Add to the mix Turkey reportedly offering to send peacekeepers to Ukraine, contingent on the war ending with Russia – and Israel, striking southern Syria and attempting to increase ties with Syrian Kurds.

Israel says it part of a new policy to demilitarize southern Syria, but the new government led by the Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) hardline Islamist group which is close to Turkey has denounced Israel.

“The Israelis also are risking by going too far into trying to punish the Syrians, forcing the Syrians, essentially to look for allies,” said Barkey on Eye for Iran.

One ally that Damascus will not reach out to is Tehran, maintaining its anti-Islamic republic stance.

“That’s it,” said Barkey on there being zero chance that Iran could reestablish itself in Syria, while Ankara enjoys a close relationship with the new HTS leaders.

“The Syrians and HTS blame Iran for propping Assad in power all these years, that Assad would not have succeeded in staying in power this long, or even winning the civil war if it wasn't for Iranian support.”

Reports: The offer of Turkish peacekeepers in Ukraine

Turkey is not signaling support of Ukraine by offering up peacekeepers, said Barkey.

Rather it's a chance for Erdogan to appear relevant on the world stage. Iran, on the other, despite its relationship with Russia, is irrelevant.

“Before Iran was a very useful if not a direct instrument of the Russians but a useful actor on the international scene because it created so many problems for the United States and its allies,” said Barkey.

Barkey questioned Iran's ability to send ballistic missiles to Russia after significant blows by Israel to its stockpile.

Meanwhile, Russia has positioned itself as a mediator between Washington and Tehran over potential nuclear talks.

"No leader has done more for Russia than Trump, so Moscow could pressure Iran," Barkey told Eye for Iran.

"It is quite possible that the Russians will put some pressure on the Iranians, whether it's real or make believe," said Barkey.

The changing alliances, new world order and the stable unpredictability of Trump, may further destabilize the Islamic Republic while Turkey gains the upper hand in the region.

You can watch the full episode of Eye for Iran with Henri Barkey, an adjunct senior fellow for Middle East studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, on YouTube or you can listen on Spotify, Apple, Amazon, Castbox or any major podcast platform.

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian stands at a critical crossroads: should he continue pushing for his political vision despite mounting opposition, or bow to pressure and step down?

In recent days, Pezeshkian has expressed growing frustration over obstacles confronting his administration.

Four issues stand out in particular: the formal adoption of the hijab law, negotiations with the United States, the impeachment of Economy Minister Abdolnaser Hemmati, and the forced removal of Strategic Deputy Mohammad-Javad Zarif from the cabinet.

Despite emphasizing "unity," Pezeshkian seems increasingly doubtful that his so-called "unity government"—which includes only four reformist ministers, while key positions remain dominated by hardliners—can deliver on his campaign promises.

Meanwhile, his political opponents, deeply entrenched in other centers of power, continue to undermine his efforts.

Signs of defiance

On Wednesday, Pezeshkian's executive deputy, Mohammad-Jafar Ghaempanah, made a striking statement on platform X, saying that Pezeshkian would continue to refuse to enforce the hijab law, despite pressure from his hardline rivals.

The law, dormant since receiving final approval from the ultra-hardline Guardian Council in mid-September, was suspended by the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) amid concerns of public backlash.

Such a decision could not have occurred without the approval of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

The President’s refusal to sign and formally announce the controversial law is therefore largely symbolic—Parliament Speaker Mohammad-Bagher Ghalibaf retains the power to activate it whenever Khamenei’s appointees in the SNSC and other power centers decide to shift their stance.

While Pezeshkian had previously voiced opposition to the hijab law, his recent statements have been more assertive. “I will not stand against the people,” Ghaempanah quoted him as saying.

Beyond this, Pezeshkian has increasingly distanced himself from policies dictated by higher authorities, including Khamenei.

Last week, he openly admitted that direct negotiations with the US to lift sanctions—something he supports—are not taking place because Khamenei opposes them.

This marks the first time an Iranian president, while still in office, has directly and publicly acknowledged a major policy disagreement with Khamenei on such a critical national issue.

Equally telling was Pezeshkian's reaction to the hardline-dominated Parliament’s impeachment and removal of the economy minister on March 2.

Under the law, the President has three months to propose a replacement to Parliament. However, ultra-hardline lawmaker Meysam Zohourian claims Pezeshkian stated as he left Parliament that he would not nominate a successor.

Additionally, over the past six months, Pezeshkian has resisted opponents' demands to remove his Strategic Deputy Mohammad-Javad Zarif from the cabinet, recognizing Zarif's potential significance in negotiations with the United States.

On March 2, after meeting with Chief Justice Mohseni-Ejei, Zarif posted on X that the Chief Justice advised him to return to academia to prevent further pressure on the government.

Government spokeswoman Fatemeh Mohajerani later confirmed that Zarif had submitted his resignation, but President Pezeshkian has not yet approved it.

Is Pezeshkian's resignation on the table?

During his campaign, Pezeshkian stated he would step down if he found himself unable to deliver on his promises.

Some reformist politicians and activists are now calling on him to follow through, arguing that if he cannot enact meaningful reforms, he should resign.

Others believe it is too early to surrender and are urging him to continue.

Meanwhile, ultra-hardliners have intensified their calls for his resignation, citing Iran’s worsening economic crisis.

Pezeshkian has not publicly addressed the possibility of resignation.

A source close to his office told Iran International Pezeshkian is feeling shaken after losing Hemmati and Zarif from his cabinet, but also said he is not a quitter.

However, emboldened by the 200 votes of no confidence against Economy Minister Hemmati—more than two-thirds of all lawmakers—ultra-hardliners could push to impeach Pezeshkian if he grows more defiant.

Under the Islamic Republic's Constitution, the president can be impeached if one-third of lawmakers support the motion. If two-thirds vote against him, he can be removed from office.

Only once in the past 46 years has Parliament taken this route—when it ousted Abolhassan Banisadr, the Islamic Republic’s first president, in 1981.