More Stories

Iran is entering a phase of persistent unrest, driven by decentralized “minor triggers” and deepening economic and legitimacy pressures that repression alone may no longer contain, senior analysts said at Iran International's townhall in Washington DC.

Iran experienced in January its most widespread and sustained unrest since the founding of the Islamic Republic, as protests spread across cities and provinces and authorities responded with an escalating crackdown that analysts say reflects a deepening crisis of legitimacy at the core of the state.

Speaking during a special Iran International Insight town hall on Wednesday, experts said the scale, persistence and decentralization of the unrest signal a structural rupture between state and society - one repression alone may no longer be able to contain.

In what participants described as one of the harshest security responses in recent years, tens of thousands have been killed, detained or interrogated. Rather than restoring order, panelists argued, the severity of the crackdown underscores mounting anxiety within the leadership about the durability of its authority.

A widening legitimacy gap

Political scientist Mohammad Ghaedi said each protest cycle deepens what he described as a structural legitimacy deficit.

“In democracies, when we ask why leaders should rule, the answer is because they are elected by the nation,” he said. “But if you ask that question of Iranians, there is no clear answer — because 47 years ago, Ayatollah Khomeini deceived the nation.”

According to Ghaedi, the leadership is fully aware of this vulnerability.

“They have to respond in a way that makes the nation unwilling to protest again. That explains the brutality of the repression,” he said.

From mega-triggers to permanent volatility

Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, a senior Iran analyst and Head of Digital at Iran International, said the protest landscape has fundamentally shifted.

“Iranian society has wisely moved from demonstrations triggered by mega-triggers to minor triggers,” he told the panel moderated by Gelareh Hon. “Minor triggers are very difficult for the government to contain because they're not centralized, they're unpredictable and they're emotionally charged.”

Instead of singular catalytic events driving nationwide mobilization, grievances now simmer across economic, social and political spheres — producing recurring, localized flare-ups that strain security forces and steadily erode the state’s ability to project control.

Sharafedin framed the crisis around three central actors: Ali Khamenei, Donald Trump and the Iranian public.

“The social contract between Khamenei and the people has expired,” he said. “Either the Supreme Leader reaches a deal with Trump at the expense of the people, or Trump sides with the people against the Islamic Republic. In both scenarios, Khamenei loses,”

Economic hardship and ideological erosion

Mohammad Machine-Chian, a senior journalist at Iran International and a former researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, argued that the unrest reflects both deep economic distress and mounting ideological rejection.

“Demanding a normal material life is in and of itself a rejection of Khomeinism — the whole ideology of the Islamic Republic, which prescribes abandonment of material life and demands sacrifice for the state” he said.

He cited soaring prices as a daily pressure reshaping public sentiment.

“Inflation is nearly 60%. Food inflation is about 72%. If we go deeper, it gets uglier — cooking oil around 200%, and red meat over 100%. This is the reality people are dealing with.”

Beyond inflation, he said, the regime’s traditional pillars are weakening. The Islamic Republic was historically sustained by an alliance between the bazaar and the mosques — institutions that once anchored its social legitimacy.

“The bazaar is finally breaking completely with the Islamic Republic,” he said. “Mosques now have detention centers. They no longer serve a social or civil purpose in Iranian society.”

Panelists also highlighted what they described as a significant psychological shift within society: foreign assistance, once politically taboo, is now openly debated.

Audience questions addressed policy trade-offs in the United States, concerns in Turkey over possible regional escalation, and the apparent weakening of Tehran’s regional proxy network.

The town hall concluded that the Islamic Republic faces converging pressures — eroded legitimacy, weakened institutions, economic deterioration and a society increasingly detached from the ideological foundations of the state. While repression may buy the leadership time, panelists said it no longer restores authority or rebuilds public consent.

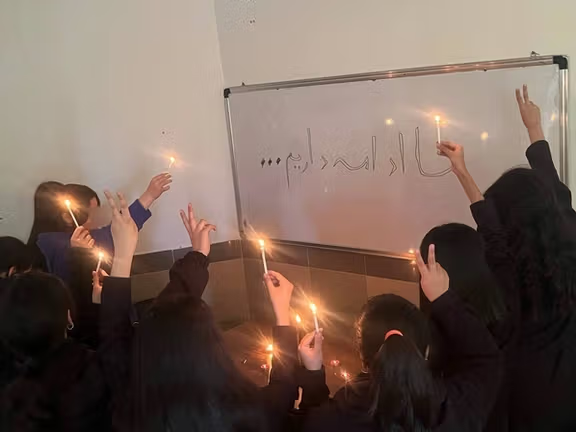

Student walkouts at schools across Iran this week underscored the continuing political presence of a younger generation that has remained deeply engaged despite months of arrests and repression.

The action, observed in numerous high schools and junior-high schools, followed a call earlier in the week by the country’s teachers’ union—one of the few remaining independent professional bodies whose members and leaders repeatedly face summons, detention and imprisonment.

The union had urged students and educators to honor those killed during the January protests, many of whom were themselves teenagers or in their early twenties.

Human rights organizations and media reports indicate that young people made up a significant share of those killed, wounded or detained during the crackdown, reinforcing the central role of Generation Z in Iran’s protest movement.

Videos circulating online on Wednesday appeared to show students—many of them girls—refusing to attend classes and instead gathering in schoolyards to sing patriotic songs in apparent solidarity with the victims.

Justice Minister Amir Hossein Rahimi acknowledged this week that a number of minors remain in detention in connection with the protests, adding that authorities were working to secure the release of some underage detainees.

At the center of unrest

Iran’s Generation Z has played a visible role in successive waves of unrest, including the nationwide protests of recent years.

Lists compiled by human rights organizations indicate that a large share of those killed or arrested were under 30, including university students and minors.

The involvement of younger Iranians reflects both demographic realities and deeper social changes.

Iran’s Generation Z has grown up during a period defined by economic instability, international isolation and increasing social restrictions. These conditions have shaped their expectations and political outlook in ways that differ from earlier generations.

A distinct identity

In a recent commentary published in the reformist newspaper Etemad, political analyst Abbas Abdi argued that Iran’s younger generation faces “multiple layers of pressure,” reflecting economic hardship, social constraints and limited political representation.

He identified several sources of tension, including declining economic opportunities, widening gaps between official norms and social realities, and what he described as the political marginalization of younger citizens.

These pressures, he wrote, have contributed to a growing sense of disconnection between younger Iranians and the country’s political establishment.

Abdi also emphasized that Generation Z is the first generation in Iran to grow up fully connected to digital networks, with access to global information and alternative sources of identity formation.

This shift has altered traditional patterns of socialization and authority. Younger Iranians are often less receptive to hierarchical forms of political messaging and more inclined toward decentralized and informal forms of expression and mobilization.

The outlook

While the state retains significant coercive capacity, the persistence of youth participation in protests suggests that underlying social and generational tensions remain unresolved.

Abdi warned that failure to address these generational pressures could deepen long-term instability, arguing that sustainable political order ultimately depends on the ability of governing institutions to adapt to social change.

The student walkouts this week, though limited in scope, reflected the enduring political consciousness of a cohort that has come of age during one of the most turbulent periods in Iran’s recent history—and whose role is likely to remain central in shaping the country’s political trajectory.

The second round of Iran–US nuclear talks was met with a muted and often critical reaction in Tehran, where official outlets questioned Washington’s commitment after American negotiators left Geneva within hours despite Iran’s offer to continue discussions.

Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi nonetheless described the talks as positive overall but cautioned that reaching a final agreement would take time. He said both sides agreed to begin drafting potential agreement texts, exchange documents and schedule a third round.

In Tehran, however, many voices sharply criticized what they portrayed as a lack of seriousness on the American side.

The government’s official daily, Iran, accused Washington of “part-time diplomacy,” arguing that the brief visit by US representatives Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner suggested an oversimplified approach to Tehran’s nuclear file.

“That’s the challenge of negotiating with non-diplomatic figures,” the paper wrote in an editorial, adding that if diplomacy is to replace pressure and tension, it must rely on “a clear and durable decision at the highest political levels.”

‘Side job for businessmen’

Commentators linked the criticism in part to the Americans’ decision to leave Geneva for separate negotiations related to the war in Ukraine, contrasting it with Tehran’s readiness for prolonged talks backed by a large expert team.

Reza Nasri, an analyst close to Iran’s foreign ministry, echoed the criticism on X, writing: “Witkoff and Kushner are treating Geneva like a diplomatic fast-food restaurant… Global stability is not fast food. Serious diplomacy requires focus and real intent, not a side job for businessmen.”

The website Nour News, close to senior security official Ali Shamkhani, also questioned Washington’s priorities in an article titled “Where is the real time-wasting?” It argued that accusations of stalling better applied to the US, which it said relied heavily on media optics and insufficiently specialized envoys.

The diplomatic exchanges unfolded amid heightened rhetoric and military signaling. Ahead of the Geneva meeting, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei reiterated his hardline stance, invoking a historical Shiite reference to stress resistance to US pressure.

Tehran media also highlighted an Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) naval exercise in the Persian Gulf, describing it as a deterrent message coinciding with nuclear diplomacy.

Iran’s financial markets reacted negatively to the Geneva talks, partly influenced by reports of an increased US military posture in the region. On Wednesday, the Iranian rial weakened again, with the dollar rising nearly 1.2 percent to around 1,630,000 rials.

Risk of talks collapsing

Political analyst Mohammad Soltaninejad cautioned that drafting preliminary texts does not signal a final deal is near.

“Even if agreement is reached on some issues, that does not necessarily mean the US will act accordingly,” he told the news outlet Entekhab.

Soltaninejad said Iran is seeking tangible sanctions relief, while the US may prefer to maintain economic pressure to gain leverage on Tehran’s missile program, raising questions about whether the sides can easily align their economic and security interests.

Another analyst, Mostafa Najafi, said in an online interview that the risk of negotiations collapsing appears higher than scenarios involving even a limited agreement to manage tensions.

Moderate journalist Ahmad Zeidabadi offered a more optimistic assessment, writing on his Telegram channel that the talks still have a chance of success.

He warned, however, that fear of domestic hardliners in Iran or pressure from supporters of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the US could derail a potentially beneficial agreement for both sides.

Forty days after more than 36,500 protesters were killed in a two-day crackdown in January, Iranians are marking the traditional chehelom not only in cemeteries but also in the streets and hospitals where the dead fell – a scale of loss that is reshaping how the country mourns.

In Iranian culture, the fortieth day after a death is a solemn threshold. Families and friends traditionally gather at the grave, laying flowers, reciting prayers and receiving visitors – a ritual of grief that is both private and communal, and that often carries religious undertones.

This week, cemeteries were only part of the picture as mourners map memory onto the sites of violence. With so many deaths concentrated in urban centers and around hospitals, intersections and residential streets, memorials have spread outward from cemeteries into the everyday fabric of cities.

Videos sent to Iran International and others circulating on social media show flowers placed not only on graves but on asphalt, sidewalks and hospital entrances – at the very spots where protesters were shot.

In Shiraz, relatives and close friends of Hamidreza Hosseinipour covered the boulevard where he was killed in petals. In Tehran’s Sadeghieh Square, citizens gathered at the traffic circle where demonstrators had been shot, laying flowers in what is normally a site of rush-hour congestion.

In Tehranpars district of the capital, mourners placed flowers and candles outside a hospital where wounded protesters were taken and where some died.

In Mazandaran province, black balloons were released into the sky.

Schools, too, became sites of commemoration. Videos show groups of schoolgirls lighting candles and singing patriotic songs, marking the chehelom inside classrooms rather than in mosques.

The sites of commemoration have widened beyond the places where many Iranians once expected mourning to unfold. Where people believe their loved ones fell, they now leave photographs, flowers or pieces of clothing.

Pavements become shrines. Traffic circles are transformed into temporary altars. Hospital gates turn into gathering points. The geography of grief has changed.

There are simply too many dead, and too many sites tied to their final moments, for remembrance to remain confined to cemetery gates.

Even when ceremonies do take place at graves, the atmosphere captured in recent videos differs sharply from older conventions of public mourning, where religious elegies used to set the tone. Today, music and movement have emerged as ways of carrying grief.

Iranians burying slain protest youths mourn with dancing and defiance

Families across Iran defy pressure to honour January protest victims

At Behesht Zahra cemetery in Tehran, footage shows families gathering and playing traditional musical instruments. In Najafabad, Isfahan province, mourners applauded and played music.

In Zanjan, kites were sent into the sky above the cemetery as names were read out.

In Shahreza, a video shows a traditional Qashqai dance performed during the fortieth-day memorial for 20-year-old Pouria Jahangiri, killed on January 8.

In Qarchak, near Tehran, mourners clapped in time to songs played for Hamid Nik, a resident who died after being hit during the crackdown. In another video from Najafabad, fireworks illuminate the night as people gather and chant.

In Mashhad, the memorial for Hamid Mahdavi – a firefighter whose act of carrying an injured protester on his back had spread widely online – took place not in silence but amid chants in the street: “For every one person killed, a thousand will rise behind them.”

These moments do not erase grief, they translate it.

The scenes appearing in recent weeks suggest a shift: not away from mourning itself, but away from a single, familiar language of mourning. Music, clapping, balloons released into the sky, kites and dance have become part of the ritual vocabulary.

After decades in which public mourning was steeped in official religious symbolism, the scenes in recent weeks suggest some are shaping something different: a mourning that is national in tone, public in form, and edged with defiance.

The fortieth day has long been a marker of closure in Iranian tradition – a moment when visitors thin out and life, at least outwardly, resumes.

But with flowers now laid on asphalt and candles lit at hospital doors, the boundary between mourning and daily life has blurred. The city itself has become the setting of remembrance – and, for many, the proof of how profoundly the culture of grief is changing.

Iranians and the government held rival ceremonies Tuesday marking the 40th day after the January 8–9 protest killings, with families staging independent memorials as officials organized a state event critics called an attempt to “appropriate” the victims.

Security forces opened fire and imposed internet disruptions as Iranians held ceremonies marking 40 days since the January protest killings, while officials organized state-led commemorations for those they described as “martyrs.”

In the Kurdish town of Abdanan in Ilam province, activists and witnesses said security forces fired live rounds to disperse hundreds of mourners gathered at a cemetery.

Videos and accounts shared online appeared to show people fleeing as gunfire rang out during chants of “Death to Khamenei.”

Unconfirmed reports said several participants were seriously injured and that a 22-year-old man, Saeed-Reza Naseri, had been killed.

Reports of clashes and gunfire also emerged from Mashhad, where social media users said security forces confronted mourners.

Internet access was severely disrupted in both cities, according to users and monitoring accounts, continuing a pattern seen during previous periods of unrest.

At the same time, the government organized its own official ceremonies, including a state event Tuesday at Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Prayer Grounds attended by senior officials such as First Vice President Mohammad Reza Aref, government spokesperson Fatemeh Mohajerani and Esmail Qaani, commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force.

A parallel ceremony was held at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad.

State media and senior officials have described the January unrest as an “American-Zionist sedition.” Participants at the official ceremony chanted “Death to America” and “Death to Israel,” and the event featured Quran recitations, religious eulogies and official tributes.

The official commemorations contrasted sharply with independent ceremonies held by families, which often included music, clapping and traditional mourning rituals.

Others questioned official claims that “terrorists” were responsible for the deaths, pointing to continued security pressure on families attempting to hold independent memorials.

Online, many Iranians accused authorities of attempting to control the narrative of the killings. “They kill and then send text messages inviting people to attend a 40th-day ceremony,” one user wrote on social media.

Despite the pressure, families of those killed held independent memorials in cemeteries across Tehran and dozens of other cities and towns. Participants in several locations chanted slogans including “Death to the dictator” and carried photos of victims, many of them young.

In Najafabad in Isfahan province, a large crowd marched toward a cemetery holding portraits of those killed. Demonstrators chanted: “We didn’t surrender lives to compromise, or to praise a murderous leader,” according to videos circulating online.

Users reported a heavy security presence at cemeteries nationwide, and in some cases closures intended to prevent crowds from assembling.

Rights groups and social media accounts said families faced pressure from security agencies to limit gatherings or avoid overtly political messaging.

The parallel ceremonies underscored the continuing divide between the state’s portrayal of the unrest and the experience of families and communities still mourning those killed.