Australia hits Iran with new sanctions over protest crackdown

Australia imposed new sanctions on 20 individuals and three entities linked to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, accusing them of involvement in a violent crackdown on protests.

Australia imposed new sanctions on 20 individuals and three entities linked to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, accusing them of involvement in a violent crackdown on protests.

“The Australian Government is today imposing further targeted financial sanctions on Iran in response to the regime’s horrific use of violence against its own people,” read a government media release on Tuesday.

The Australian government said those sanctioned include senior IRGC officials and entities that violently suppress domestic protests and threaten lives inside and outside Iran.

Among those named are Iran’s national police chief Ahmad-Reza Radan, who has been a central figure in directing street-level repression, mass arrests and the use of force against protesters.

Intelligence Minister Esmail Khatib was also on the list. He oversees the security and intelligence apparatus responsible for surveillance, detentions and interrogations of activists and dissidents.

Ali Fazli, a senior IRGC commander and former Basij chief, who has long been associated with suppressing protests and coordinating paramilitary forces against demonstrators, was also sanctioned by Canberra.

Other notable names on the list included Mohammad Reza Fallahzadeh, a senior commander in the IRGC’s Quds Force, Mohammad Saleh Jokar, a former commander of student Basij forces, and Yahya Hosseini Panjaki, the intelligence ministry's deputy for domestic security.

Canberra’s sanctions also targeted the IRGC Cyber Defense Command, involved in online surveillance and information control; IRGC Quds Force Unit 840, a covert unit accused of planning operations against dissidents and foreign targets; and the IRGC Intelligence Organization, which oversees domestic intelligence, arrests and interrogations and plays a central role in suppressing protests inside Iran.

The Australian government said the new measures build on earlier step of listing the IRGC as a state sponsor of terrorism and its existing sanctions framework on Iran.

Australia officially designated IRGC as a state sponsor of terrorism in November after intelligence linked the group to attacks on Jewish centers in Sydney and Melbourne.

The Guards, who have been designated a terrorist organization by the United States since 2019, were also put on the EU’s terrorist list in late January.

The Albanese government has so far sanctioned more than 200 Iranian individuals and entities, including more than 100 linked to the IRGC.

Israelis and Iranians have been cast as enemies for so long, but during Iran’s uprisings their voices tell a different story as Iranians drew a line between themselves and the Islamic Republic.

In late September 2022, when a young Iranian woman named Mahsa Amini was killed for showing her hair, Iran erupted. Millions of brave Iranians, women and men, young and old, took to the streets.

What followed was not just a protest against compulsory hijab laws, but one of the clearest rejections of the Islamic Republic since 1979: Woman. Life. Freedom.

At the time, I was head of digital operations at the Israel ministry of foreign affairs, leading Israel’s public diplomacy online in six languages, including Persian.

From the start, we distinguished between the Islamic Republic and the Iranian people. That distinction guided everything we did. We launched one of the only official digital campaigns anywhere in direct solidarity with Mahsa Amini and the protesters, including a filter viewed more than a million times.

Our Israel in Persian accounts exploded. Posts expressing support reached millions. Every day, we received thousands of messages from inside Iran: “Thank you for seeing us,” they said, “be our voice.”

In January 2026, they did the same.

For more than four decades, the Islamic Republic has insisted that hatred of Israel is central to Iranian identity. But millions of Iranians have told us otherwise.

A GAMAAN survey published in 2025 found that roughly two thirds of Iranians said the government should stop its “destroy Israel” rhetoric, and a similar majority viewed the recent 12 day conflict as between the Iranian regime and Israel, not between Israel and ordinary Iranians.

Loyal supporters of Iran's theocratic rule, the same voices that celebrated October 7, want you to believe Iranians hate Israel and that the protests are foreign engineered fantasies.

They flood social media with trolls, lies, and fake AI videos. But the people have already spoken. Across ideology and geography, they are saying the same thing: Not death to Israel. Not death to America. Death to the Islamic Republic.

Hundreds of thousands of Iranian Jews live around the world today, many still speaking Persian, cooking Iranian food, and aching for the country they were forced to leave.

Israel is home to about 200,000 Iranian Jews. Long before modern politics, Cyrus the Great liberated the Jews from exile and allowed them to return to Jerusalem, an event recorded in both Jewish and Persian history.

That shared past still lives between our peoples. And it lives in everyday encounters.

Every Iranian I have ever met has responded to me as a Jewish Israeli with warmth, curiosity, and respect. Never hatred.

Israelis are taught that Iran wants them wiped off the map. Iranians are taught that Israel is satanic and responsible for their suffering. But we both know the truth. It is the Islamic Republic that threatens both of us.

The rulers in Tehran have destroyed Iran’s economy, murdered teenagers for defying religious rule, and crushed dissent. They send money to their armed allies in the region while ordinary Iranians struggle to afford food and medicine.

Inside Iran, protesters chant, “Not Gaza, not Lebanon, my life for Iran.”

For Israelis, the danger is existential. The same regime that brutalizes its citizens openly calls for Israel’s destruction and races toward nuclear capability.

Israelis and Iranians do not need permission to recognize each other. Beneath decades of forced slogans lies something older and stronger than propaganda.

When Iranians rose up, Israelis didn’t see enemies in the streets of Tehran. We saw courage. And just as Iranians amplified Israeli voices after October 7, we understand that now it is our turn to speak for them.

This is not a Zionist conspiracy. It is human beings standing up for human beings.

The Islamic Republic fears that if Israelis and Iranians ever meet as people rather than caricatures, its mythology would collapse. So we stand with our Iranian brothers and sisters as allies, determined to answer their call for help.

For Jews, “Next year in Jerusalem” is a prayer for freedom. Today, that prayer has an echo: Next year in Tehran.

Reza Bahmani Alijanvand, a 34-year-old Iranian protester, disappeared after attending protests in the central Iranian city of Shahin Shahr on January 8, and was later found dead in the cold storage of a cemetery, people familiar with the matter told Iran International.

The sources said Alijanvand was shot by security forces with two live rounds, one striking his lower back and another his abdomen. His family spent five days searching hospitals, police stations and prisons across Isfahan province before identifying his body in the cold storage at Bagh-e Rezvan cemetery on January 13, the sources said.

According to the sources, Alijanvand's body was transferred later that night, on January 13, to Shahin Shahr's morgue.

Authorities initially refused to hand over the body and sought to have Alijanvand declared a “martyr,” a condition the family rejected, which would have required them to accept the state’s official account of the death rather than acknowledge that he was killed by state security forces.

Alijanvand was eventually buried under heavy security at around 4 a.m. on January 15, in a tightly controlled ceremony at Behesht-e Zahra Chaharbisheh cemetery in his hometown of Masjed Soleyman in southwestern Iran, with only five family members present and several plainclothes agents in attendance, the sources said.

Alijanvand was married and worked as a forklift driver at a brick factory, according to the people familiar with the matter.

“Reza worked from morning until night. He was deeply patriotic and hopeful for Iran’s freedom,” the source said, adding that Alijanvand believed Iran’s exiled prince Reza Pahlavi would return to the country.

Last month, Iran International reported that more than 36,500 Iranians were killed by security forces during the January 8-9 crackdown on nationwide protests, making it the deadliest two-day protest massacre in history.

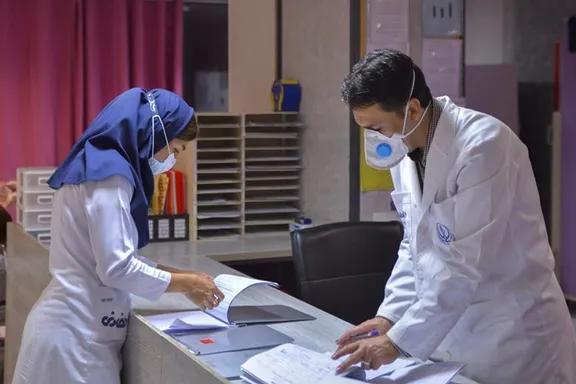

Rights groups and activists are sounding the alarm over what they describe as a widening campaign of pressure, arrests and intimidation against Iranian doctors and nurses who treated injured protesters.

Iran International has reviewed information from multiple sources inside Iran suggesting that at least 32 members of the country’s medical staff have been detained, with no public information available about the status of their cases.

Doctors who treated wounded protesters in cities including Qazvin, Rasht, Tabriz, Mashhad and Gorgan have been arrested or have gone missing, according to the reports.

Most of the reported arrests are said to have taken place after January 8, following the escalation of protests and the ensuing security crackdown.

‘Normalization of arrests’

Iran Medical Council chief Mohammad Raiszadeh confirmed that 17 of its members had faced judicial or security cases linked to the recent unrest, but insisted that none had been prosecuted for providing medical treatment and that no verdicts had been issued.

The Medical Council is formally a civil body but operates under heavy state oversight.

Raiszadeh, who is close to conservative political circles and previously led the establishment-aligned Basij Doctors Organization, said the council had followed up the cases with security and judicial authorities and had been told that none of the individuals were arrested solely for treating patients.

His remarks prompted criticism within the medical community.

Mahdiar Saeedian, editor-in-chief of a medical science magazine in Iran, wrote on X that the council’s position amounted to normalizing state pressure on healthcare workers.

“More unpleasant than silence is the normalization of arrests and pressure on medical staff by the Medical Council,” he wrote. “This is the result of fully turning a professional organization into a state-controlled body.”

Reported cases

UK-based outlet Kayhan London reported that doctors Masoud Ebadi-Fard Azari and his wife, Parisa Porkar, were arrested in Qazvin for allegedly treating injured protesters, adding that their whereabouts remain unknown.

Another reported case involves Golnaz Naraqi, a 41-year-old emergency medicine specialist at Hasheminejad and Shohada-ye Tajrish hospitals in Tehran, who was reportedly arrested at her home more than ten days ago.

Social media users have also reported growing pressure on medical staff accused of helping protesters anonymously.

In one account, a viewer message sent to Iran International said Farshid Pourreza, head of Golsar Hospital in Rasht, was dismissed and expelled from the hospital for supporting protesters and treating the wounded.

Health Minister Mohammad Reza Zafarghandi wrote on X that providing “the best possible medical services to every patient in a safe healthcare environment,” regardless of “any external factors,” was the health system’s top priority.

The remarks drew swift criticism online.

“As a colleague, I am waiting to see whether you remain loyal to your oath, or whether an ‘external factor’ stands in the way of it,” Nakisa Serafinincho, an Iranian doctor based in Romania, wrote on X.

Another user responded: “You can’t even protect medical staff. How can you talk about patient safety?”

As Iranians mourn those killed in the nationwide crackdown, state-aligned voices are falling back on familiar defenses: downplaying the toll, casting the protests as a foreign plot, and stripping victims of civic status by branding them religious enemies.

Variations of this message have surfaced across pro-government platforms, from seminarians presenting bloodshed as “righteous” to well-connected insiders arguing that killing protesters in the street is cheaper than arresting and executing them one by one.

A week after Iran killed more than 36,500 people, a state-affiliated analyst, Hesamoddin Haerizadeh, framed the protests not as civic dissent but as a divinely charged war, wrapping state violence in religious and moral language.

Opening his remarks, Haerizadeh cast the uprising as an externally orchestrated assault, describing the unrest as foreign backed riots and part of a broader confrontation between the Islamic Republic and the "non-believers front."

From there, he moved beyond political framing into a religious logic that treats street protests as a battlefield where killing is not a crime but an inevitable feature of a sacred struggle.

Haerizadeh branded the protests as “armed rebellion,” insisting that what had taken place was not peaceful protest but organized violence.

Haerizadeh then introduced an explicitly theological lens, portraying the crackdown as part of what he described as a divine process of purification.

“These events are meant to separate the impure from the pure,” he said, adding that turmoil is necessary so that “the impure are distinguished from the pure.”

In one of the starkest passages, he cited a Quranic verse often used to legitimize violence against perceived enemies: “And fight them until there is no more fitna,” he said, quoting scripture, “until religion is entirely for God.”

Critics say the effect of this framing is to turn the killing of protesters into something sacred: not a state decision, but a divine sorting mechanism—a form of moral cleansing.

Haerizadeh’s rhetoric relied heavily on dehumanization, dividing society into moral categories rather than citizens with rights.

“Kill, but with a ‘pure heart,’” activist Ahmad Batebi wrote, arguing that the lecture was designed to allow perpetrators to believe: “I didn’t kill; God sifted.”

The civic technology group TavaanaTech described the session as “workshops for killing and murder,” warning that such religious framing lowers the moral barrier to atrocity.

“This language is the language of genocide,” the group wrote, “a language that first makes the victim worthless so killing becomes easier.”

Killing as bureaucratic efficiency

A separate set of remarks, contained in an audio file attributed to Ahmad Ghadiri Abyaneh – the son of a former senior Iranian diplomat – moves beyond ideology into blunt cost-benefit logic.

In an online session on Thursday, January 29, he argued that killing protesters in the street could spare the Islamic Republic the international pressure that follows formal executions.

He minimized the scale of the deaths, reducing reported killings from tens of thousands to just over 3,000, and said the cost of killing protesters on the streets was far lower than arresting and executing them one by one.

“Why didn’t you kill them on the streets?” he asked, addressing the authorities. “You know that if they had been eliminated on the spot, the cost to the system would have been far, far lower than if you tried to execute them one by one.”

“Each one becomes a case file and a source of pressure on the Islamic Republic,” he continued. “By any logic—by any religious reasoning—it would have been right to show an iron fist with a decisive strike and wipe them out on the scene.”

Mockery on state television

The narrative hardened further when a host on Ofogh TV, an IRIB channel affiliated with the Revolutionary Guards, mocked reports that thousands of bodies had been transported in refrigerated trailers.

“What type of refrigerator do you think the Islamic Republic keeps the bodies in?” he asked sarcastically, offering joking options including an “ice cream machine” and a “supermarket freezer.”

The remarks sparked outrage across Iran’s political spectrum. IRIB later removed Ofogh TV’s director, Sadegh Yazdani, and pulled the program, though many critics said deeper accountability was unlikely.

'Enemies of God'

The same logic resurfaced on Sunday, when Tehran City Council head Mehdi Chamran denied protest deaths while labeling victims with one of the Islamic Republic’s harshest religious-legal categories.

“In these protests we had no deaths, and only moharebs were present with guns and knives,” Chamran said.

The term mohareb –used for those accused of waging war against God – has long been associated with the harshest punishments, including execution. Critics say it functions as a rhetorical weapon, transforming civilians into divine enemies.

Taken together, these remarks point to a single through-line: Tehran's effort to frame violence as either sacred duty or bureaucratic convenience.

Iran International has documented the deaths of more than six thousands people during recent protests in Iran whose names do not appear on an official government list published over the weekend.

“In a shameful attempt to downplay the scale of the largest street massacre in Iran’s contemporary history, Tehran has sought to cast doubt on the figures reported by Iran International,” the broadcaster’s editorial board said in a statement on Monday.

“Yet the statistics released by the government itself constitute further evidence of their dishonesty.”

The list published by Tehran includes 2,986 names. Fewer than 100 of those overlap with the 6,634 deaths compiled by Iran International since it issued a public call for documentation from families, witnesses and citizen journalists.

The information collected includes victims’ names, photographs, places of residence, circumstances of death and testimony from relatives, gathered despite severe internet restrictions and security pressure on families inside Iran.

Protests erupted in late December and escalated sharply on January 8 and 9, following a call for nationwide action by the exiled prince Reza Pahlavi. The demonstrations were met with a sweeping security crackdown in which thousands were killed and many more wounded or detained.

Iran International has previously put the death toll at at least 36,500, citing leaked official documents—a figure Tehran disputes.

The government’s release of an official “casualties list” appears to have been intended as a rebuttal to that report, but it has instead triggered a backlash.

Critics, including families of victims and activists, have pointed to alleged errors, duplicated identities, inconsistencies in official figures, and the absence of information about unidentified bodies and missing persons.

Iranian officials say the discrepancies stem from the presence of unidentified remains—a claim critics question given the scale of the state’s security and forensic apparatus.

You can read the full statement by Iran International’s editorial board here.