Variations of this message have surfaced across pro-government platforms, from seminarians presenting bloodshed as “righteous” to well-connected insiders arguing that killing protesters in the street is cheaper than arresting and executing them one by one.

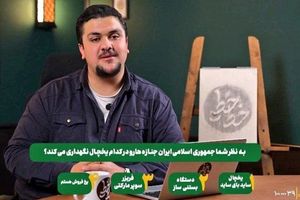

A week after Iran killed more than 36,500 people, a state-affiliated analyst, Hesamoddin Haerizadeh, framed the protests not as civic dissent but as a divinely charged war, wrapping state violence in religious and moral language.

Opening his remarks, Haerizadeh cast the uprising as an externally orchestrated assault, describing the unrest as foreign backed riots and part of a broader confrontation between the Islamic Republic and the "non-believers front."

From there, he moved beyond political framing into a religious logic that treats street protests as a battlefield where killing is not a crime but an inevitable feature of a sacred struggle.

Haerizadeh branded the protests as “armed rebellion,” insisting that what had taken place was not peaceful protest but organized violence.

Haerizadeh then introduced an explicitly theological lens, portraying the crackdown as part of what he described as a divine process of purification.

“These events are meant to separate the impure from the pure,” he said, adding that turmoil is necessary so that “the impure are distinguished from the pure.”

In one of the starkest passages, he cited a Quranic verse often used to legitimize violence against perceived enemies: “And fight them until there is no more fitna,” he said, quoting scripture, “until religion is entirely for God.”

Critics say the effect of this framing is to turn the killing of protesters into something sacred: not a state decision, but a divine sorting mechanism—a form of moral cleansing.

Haerizadeh’s rhetoric relied heavily on dehumanization, dividing society into moral categories rather than citizens with rights.

“Kill, but with a ‘pure heart,’” activist Ahmad Batebi wrote, arguing that the lecture was designed to allow perpetrators to believe: “I didn’t kill; God sifted.”

The civic technology group TavaanaTech described the session as “workshops for killing and murder,” warning that such religious framing lowers the moral barrier to atrocity.

“This language is the language of genocide,” the group wrote, “a language that first makes the victim worthless so killing becomes easier.”

Killing as bureaucratic efficiency

A separate set of remarks, contained in an audio file attributed to Ahmad Ghadiri Abyaneh – the son of a former senior Iranian diplomat – moves beyond ideology into blunt cost-benefit logic.

In an online session on Thursday, January 29, he argued that killing protesters in the street could spare the Islamic Republic the international pressure that follows formal executions.

He minimized the scale of the deaths, reducing reported killings from tens of thousands to just over 3,000, and said the cost of killing protesters on the streets was far lower than arresting and executing them one by one.

“Why didn’t you kill them on the streets?” he asked, addressing the authorities. “You know that if they had been eliminated on the spot, the cost to the system would have been far, far lower than if you tried to execute them one by one.”

“Each one becomes a case file and a source of pressure on the Islamic Republic,” he continued. “By any logic—by any religious reasoning—it would have been right to show an iron fist with a decisive strike and wipe them out on the scene.”

Mockery on state television

The narrative hardened further when a host on Ofogh TV, an IRIB channel affiliated with the Revolutionary Guards, mocked reports that thousands of bodies had been transported in refrigerated trailers.

“What type of refrigerator do you think the Islamic Republic keeps the bodies in?” he asked sarcastically, offering joking options including an “ice cream machine” and a “supermarket freezer.”

The remarks sparked outrage across Iran’s political spectrum. IRIB later removed Ofogh TV’s director, Sadegh Yazdani, and pulled the program, though many critics said deeper accountability was unlikely.

'Enemies of God'

The same logic resurfaced on Sunday, when Tehran City Council head Mehdi Chamran denied protest deaths while labeling victims with one of the Islamic Republic’s harshest religious-legal categories.

“In these protests we had no deaths, and only moharebs were present with guns and knives,” Chamran said.

The term mohareb –used for those accused of waging war against God – has long been associated with the harshest punishments, including execution. Critics say it functions as a rhetorical weapon, transforming civilians into divine enemies.

Taken together, these remarks point to a single through-line: Tehran's effort to frame violence as either sacred duty or bureaucratic convenience.