Flames of port blast are out but we're burning inside

Another disaster, more Iranians killed, no one held accountable, the media gagged: the port blast on Iran’s Persian Gulf coast was news and not news at the same time.

Firsthand reports from contributors inside Iran

Another disaster, more Iranians killed, no one held accountable, the media gagged: the port blast on Iran’s Persian Gulf coast was news and not news at the same time.

The explosion struck Bandar Abbas, one of Iran’s most vital trade arteries. It cloaked the city in toxic fumes. Schools and government offices were shut, residents were told to stay home and wear masks. Yet officials tried to downplay the severity.

Soon speculations and gossip rivered, as is the case usually, to fill the vacuum left by the state’s evasion.

“You won’t get shock waves 5km away if the blasted containers had sugar or wheat,” my friend Navid, an English instructor, told me shortly after the news came in.

“It has to be explosives,” he posited, “weapons hidden among civilian cargo to protect it from attacks. They don’t care about the human cost.”

Most casualties were port workers, ensuring the flow of goods in and out of the country. As the numbers rose, public fury deepened.

Unofficial accounts pointed to sodium perchlorate and other compounds imported from China for Iran’s missile program. Authorities denied any such link, and one state news report quoting customs officials suggesting improper storage practices was quietly deleted hours later.

The belief that such cargo may have been stored without workers’ knowledge, possibly to shield it from foreign attack, has inflamed a population fed up with incompetence and injustice.

“Either it’s criminal negligence or a deliberate act. And I’m not sure which is worse,” says Amin, who works for a logistics company. “Some say it was Israel, though they denied it instead of their customary silence. But even if it was an Israeli operation, I’d still blame those who hid military cargo among commercial goods.”

Amin is 47, the same age as the Islamic Republic, he reminds me. “My whole life is gone, wasted, under this brutish bunch.”

The frustration, the rage, in Amin’s voice is perhaps the most common emotion I see around me these days. And those in power appear mostly indifferent or oblivious. And I’m not sure which is worse–to borrow Amin’s words.

“Did you see the transport minister on TV,” my doctor’s secretary, jumps at me before I can barely say hello. “Oh my God, she sounded like a game show host, smiling that ‘all is fine’ while the port was in flames and people were going crazy not knowing what had happened to their loved ones.”

She is of the talkative type I would ignore if I weren't researching for a story.

“And then that half-wit (president) Pezeshkian, oh my God, he pays a visit to bed-bound, shell-shocked victims and jokes about walking out of the hospital. At least pretend you care,” she added.

Pezeshkian and his transport minister Farzaneh Sadeq are under fire. The latter has a motion of impeachment waiting for her in the parliament. She likely knew nothing about the containers. As the only female minister, she’s the perfect scapegoat, the “shortest wall” to knock down as we say in Persian.

The only ones held ‘accountable’ here are those trying to shed light on a tragedy. Reporters on the scene have been threatened and silenced. Papers in Tehran have been gently reminded to tow the official line.

“Our editors have received the infamous call,” says Elham, a journalist at a moderate daily. “And they relay the message to us: don’t engage in ‘illegal’ activity. God knows what that even means. We just want to report what we find out.”

After ten days, the port flames are gone. But the fire burning in us—the one lit by the Islamic Republic’s contempt for truth and life—shows no sign of dying down.

A new marketing display by Iranian brand My Lady featuring transparent packaging for sanitary pads has ignited online debate, revealing the deep cultural discomfort still surrounding menstruation in Iran.

The display, first posted by a user on the social media platform X last week, showed a row of pads visible in see-through folders—an abrupt break from the longstanding norm of black plastic bags and whispered requests at the counter.

The post quickly surpassed one million views and gathered thousands of likes and shares. “From black plastic to product albums to help us choose better. What a path we’ve come, woman!” wrote one user, who reposted the image with commentary that resonated widely.

Others joined the conversation with similar stories of resisting the imposed shame around buying menstrual products in public.

The marketing choice—practical on its face—has gained symbolic weight in a country where women’s bodies are policed not just through law but through entrenched taboos.

“Seven years ago, when My Lady launched its maxi pads, we had to secretly open samples for customers,” wrote a user identifying as a company marketer. “The store manager scolded us, said it was shameless. So we made a discreet booklet with three samples stuck inside—like contraband.”

The move to make pads visibly accessible in stores echoes moments from the 2022 protests, when women were photographed covering surveillance cameras in Tehran’s subway with sanitary pads—turning a product once treated as unmentionable into a symbol of defiance.

That imagery reinforced a broader shift: menstruation was no longer something to be hidden, but something women could use—literally and figuratively—to resist.

In a post viewed more than 800 times, another X user described how, in smaller towns, buying pads still carries a strong social stigma. “I’d say put it in a regular bag, and I’d relish the look on the seller’s face,” she wrote. “You could see them thinking, ‘How shameless the new generation has become.’ It was deeply satisfying.”

That stigma, rooted in religious and patriarchal frameworks, frames menstruation as impure. Across various cultures with strong religious influences, menstruating women are often deemed unclean and barred from certain spaces. The expectation is silence—both about the blood and the discomfort.

In Iran, where the Islamic Republic’s laws tightly govern gender expression and public morality, that silence is rigorously enforced.

Still, the shift is underway. A handful of men have joined the conversation online, recalling how they were dispatched to buy pads to shield female relatives from embarrassment.

“I’d run home with the black bag, praying no one saw me,” one wrote. But others mocked the change, reflecting a lingering cultural divide. Of 84 replies under one widely shared post, 11 came from male accounts opposing the visibility initiative.

The company behind the display, My Lady, has previously drawn official backlash. In March, following the release of a video marking International Women’s Day—one that referenced women’s exclusion from stadiums and legal rights—their Instagram page was taken down. Still, the public rallied, citing the brand’s decade-long focus on education and taboo-breaking.

The rise of transparent packaging may not end the stigma, but its presence in plain sight signals a societal reckoning.

The journey from hushed exchanges to open acknowledgment continues, carried forward by a generation of women unwilling to be hidden.

Iranian authorities have refused to register a newborn named Guntay, denying him a birth certificate and healthcare access over what they called the name's non-compliance with Iranian and Islamic cultural norms.

The child, born on April 22, remains without official identification over a week later.

The parents from Parsabad, a city in Iran’s northwestern Ardabil province, were informed that the name Guntay was deemed unsuitable by the national registry on the grounds that it did not align with what authorities classify as “Iranian and Islamic naming conventions," according to HRANA, a US-based news outlet focused on human rights in Iran.

“This is not the first time the government has interfered in our choice of names,” a source told HRANA. The source said the parents have filed a formal complaint and are pursuing the matter through legal channels.

Without a birth certificate, the child is unable to access basic services including healthcare and legal identity, HRANA reported.

The outlet added that the experience has imposed psychological and administrative strain on the family.

Iran's civil registry system has a documented pattern of rejecting names perceived to originate from non-Persian ethnic traditions. A similar case last year in Tabriz saw authorities block issuance of birth certificates for triplets named Elshen, Elnur, and Sevgi, all Turkish names.

Although a court later ruled in favor of the parents, the registry appealed the decision, sending the case to a higher court.

Under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Iran has signed, every child must be registered immediately after birth and has the right to a name and nationality. Article 7 of the convention specifically affirms these entitlements, while Article 2 prohibits discrimination based on language or ethnicity.

Iran’s civil registry defends its policies by citing cultural preservation. "The selection of names that insult Islamic sanctities, as well as titles, epithets, and obscene or gender-inappropriate names, is prohibited. Individuals bearing such names must take action to change them," it says on its website.

The agency maintains a name selection database and offers a name interaction system designed to guide parents toward what it calls Iranian and Islamic options.

Critics, including human rights groups and legal scholars, say the law reinforces state control over cultural expression and disproportionately affects the country's wide array of ethnic minorities in provinces with higher populations of them such as Kordestan, Khuzestan, and Sistan and Baluchestan.

I’ve grown the habit of checking the dollar exchange rate every few hours, even though I sold all that I had a few months ago—or perhaps because I sold all that I had a few months ago.

Late last year, when I did that, the dollar was 68,000 tomans. Two weeks ago, it hit an all-time high of 102,000. Then it started dropping sharply when Tehran and Washington began negotiating.

It’s now an almost masochistic exercise, calculating how much my partner and I could have gained had I waited a little bit longer.

Over the last six-seven years, we converted whatever we had and could save into dollars. It stood at around $20,000 in the fall of 2024.

We kept the cash at home, living in constant fear of a break-in. But we didn’t trust the banks either. People’s foreign currency deposits were once forcibly converted to rials during a currency collapse in the early 2010s. Public trust was shattered.

Our savings weren’t enough to buy a home in Tehran. Renting here, with inflation this brutal, is terrifying. Prices climb relentlessly. Our income doesn’t. Half of what we earn goes straight to rent.

Then the war drums began to beat louder. The Israeli-Iranian cold war heated up with missile attacks and airstrikes. War felt closer than ever. We went to bed each night bracing for the worst.

That’s when we made our decision: we’d buy a home outside Tehran—somewhere to safeguard our money, and ourselves, if war came. A property in the capital was out of reach anyway. A small 600 sq ft apartment in a modest neighborhood would cost about 5 billion tomans. We had less than two.

Even ChatGPT approved our thinking.

“If you're buying as a refuge, stay away from military centers and major cities, and prepare for wartime shortages,” it said.

We found an old 2000 sq ft house in a small town in Iran’s northern province of Gilan, far from military sites and with clean air. We sold our dollars overnight, sold the little jewelry that we had, and borrowed 600 million tomans to close the deal at 2.5 billion.

We couldn’t move. We’re both job-bound to Tehran. But now we had a place to escape to. A safe investment. A backup life.

Almost immediately, as if waiting for us to get rid of our assets, the dollar and gold surged. We couldn’t help calculating what we’d lost. It was dreadful. And all the more so because we had been advised against it by our family. “Why sell when the dollar is rising?” they said.

The stress and the anxiety boiled over into a fight. My partner kept saying “I told you so.” He hadn’t. Eventually, we decided and promised not to revisit the issue, but privately, we both still do. We check the rates. We run the numbers in our heads.

Since these US-Iran talks began, I’ve been torn. A deal with Donald Trump could bring much-needed cash to the government’s coffers. Would it ease the people’s hardship? Most likely not. It would only benefit Iran’s bloated IRGC-led oligarchy and its loyal forces inside and abroad.

Still—for now at least—the threat of war feels more distant. That offers a fragile peace of mind.

But Many are not even torn. In a recent poll on Telegram, seven in ten of over 5,000 participants said they’d rather the deal fell apart and the Islamic Republic was attacked. I can’t say this reflects society as a whole, but I know more than a few who oppose a deal because they believe it prolongs the theocratic rule in Iran.

Even the dip in the exchange rate hasn’t brought joy. Prices haven’t dropped. Inflation hasn’t eased. And the rule still holds: we earn in rials, we spend in dollars.

For me, personally, the falling dollar has brought a strange feeling of comfort. It makes the choice we made feel a little less like a loss.

My 23-year-old cousin, Ali, newly married and the father of a two-month-old baby, was killed in the Iran-Iraq war in 1985. From that moment, everything in my uncle’s family changed.

As talk of another war grips the nation, the devastating legacy of the Islamic Republic's defining conflict casts a long shadow.

Before Ali’s death, my female cousins, his sisters, were the main supplier of pop music in our extended family, duplicating cassette tapes that were banned by the ever-encroaching Islamic rules. They were good dancers too, showing us younger ones how to shake hands and bottoms in tandem.

And then their brother, my cousin, died—martyred, in their words. Overnight, they became observant Muslims. They had to. They all adopted the chador, the black cloth covering all but a woman’s face. My cousin’s 21-year-old widow also joined the ranks of women in black, absorbed into a new world of mourning and restriction.

A year later, one of my cousins, the martyr’s younger sister, got married. She had a wedding only in name. There was no dancing, no music, no clapping or loud cheering.

This transformation was common among families who lost loved ones in the war. The Islamic Republic, having cemented its rule after the revolution, framed the war as a religious not a national affair.

The Sacred Defense, it was called - a holy struggle to preserve Islam.

Those killed in the war had given their lives for their faith, the state propaganda went. So for their family to turn away from that faith would be to dishonour their memory and blood.

The martyrs were glorified by the state, not as national heroes but as loyal servants of the faith and its embodiment, Ayatollah Khomeini. As such, their families received benefits—monthly stipends, housing assistance, government jobs, university admissions quotas.

In a country racked by war, poverty, and cutthroat competition for higher education, these privileges created a rift between martyr families and the rest of society.

Atefeh, Ali’s daughter, was born two months after her father got killed. She is 40 now, recalling her life as a martyr’s daughter, a life she had never chosen.

“I never saw my father, but his shadow fashioned my life,” Atefeh says. “The pressure was too much for little children like me. They kept telling us we had to honor his sacrifice and follow our fathers’ or brothers’ path. What was their path, though, I wonder. My dad’s wasn’t Islam, for sure, if the few pictures we have of him are any clue.”

Atefeh attended one of the many Shahed schools, established for the children of martyrs. She says she always wanted to attend a regular school and blend in. But she was constantly reminded that she had to be a role model because of her father—that she was obligated to be ‘modest’: to wear long and loose clothes, avoid boys, shun fashion, close her ears to music and open instead to the words of God, the Quran.

“Sometimes, I hated my father and the fact that we were part of a martyr’s family,” she says.

As she grew, Atefeh fought harder with her mother and managed to convince her to go to a regular high school. She wanted to be ‘normal’, as she puts it. She tried to hide her father’s fate even. But it wasn’t that easy.

“Being a martyr’s daughter meant people saw me a certain way before even meeting me,” Atefeh says. “Other girls at school assumed I was religious and had no interest in the things they enjoyed. It was an Ugly Duckling kind of situation.”

On the other side, the authorities at school scolded her for not being strict enough, constantly reminding her that her father had died for the hijab and she had to have a proper one.

“But nowhere in my father’s will did he mention the hijab,” Atefeh says with a bitterness that comes off a long, dulled anger. “That was just a lie, or a gross exaggeration at the very least, by the government, to claim that martyrs prioritized women’s veiling.”

Because of the pressures she endured growing up, Atifeh refused to use the university admissions quota for martyr families. She didn’t want the privilege, but others assumed she had taken the spot of a more qualified student. She rarely had the opportunity to explain herself.

As public resentment toward the government grew, so did hostility toward martyr families. Many saw them as symbols of the regime, beneficiaries of an unjust system.

Some children of high-profile martyrs have tried to distance themselves from the government in recent years, openly criticizing its actions. But the state has so thoroughly co-opted the image of martyrdom that shedding the label is nearly impossible.

In February, when a group of Iran-Iraq war veterans and commanders announced plans to protest the 15-year house arrest of war-time prime minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi and his wife Zahra Rahnavard, they were detained—and the public barely reacted.

Atefeh has been an outspoken critic of Iran’s ruler for quite a while. She despises them and ‘their martyr enterprise‘ as she puts it.

“I never say or write that I am a martyr’s daughter when I criticize the government because even that feels like an unearned privilege,” she says.

Over the years, my female cousins fought to remove their chadors, and more recently, their headscarves. It took decades for Atefeh and her aunts to reclaim even minimal personal freedoms and shape their own lives.

But changing public perception has proved almost impossible.

Iranians—a vast majority at least—are angry with their near-half-century-old theocratic rule. They are fed up with everything it stands for and promotes, including the "martyr enterprise" in Atefeh’s words.

“It’s hard to blame people for lumping together martyr families and the Islamic Republic,” she says. “Many deserve it for becoming part of the system or shutting up to gain something. But some gained nothing and are stigmatised nonetheless. It’s all fair perhaps, but it’s painful too.”

Soroush Salehi campaigned to have Canada label Iran’s Revolutionary Guards a terrorist group but now the law for which he strived may eject him and others forced into the group as conscripts.

In June of last year, Soroush celebrated Canada's decision to list the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist entity.

Little did he know, however, that his activism to ostracize the group that had dragooned him into service would upend his own life.

Soroush is part of a community of Iranians living in Canada who bitterly resent their country's rulers for impressing them into the Islamic Republic's security forces.

Along with the regular military and police, the IRGC is another agency that Iranian men could be forced to join to complete their mandatory military service.

A transnational paramilitary force, the Revolutionary Guards spearhead Tehran's influence in the Middle East, including training and arming of affiliates like Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis and Iraqi militias.

Now their lives on Canadian soil are in jeopardy and are left to the discretion of immigration officers who may deem them inadmissible under the new policy.

Iran International spoke to Soroush and two other Iranian nationals whose permanent residency applications are also in limbo and who do not wish to be identified due to security concerns. Iran International has also reviewed evidence demonstrating the men were conscripts and not permanent IRGC servicemen.

From advocate to victim

Soroush Salehi washed dishes and carried out other menial tasks and errands as an IRGC conscript fulfilling his mandatory service more than 18 years ago in Iran.

The mechanical engineer moved to Calgary, Alberta in search of a peaceful life, leaving his theocratic homeland where he saw no future.

He came to Canada in 2022 in the same year Iran's clerical rule saw the biggest challenge to their system in decades as the so-called Woman Life Freedom protest movement swept the country, only to be quashed with deadly force.

Soroush chose Canada after being rejected by the United States in 2020, despite his wife's American citizenship, after US immigration authorities deemed him a “member of a terrorist organization.”

After US President Donald Trump put the IRGC on the US terrorist list in 2019, no exemptions were made for conscripts. Promises by President Joe Biden’s administration to look into exempting conscripts never materialized.

Now Soroush may be deemed inadmissible in Canada, too. Soroush is currently a temporary resident under a work permit and if no exemptions are provided, he might be deemed inadmissible and deported.

“I had dreams with my wife for a life here. Everything was good until September 2024,” Soroush told Iran International, “All my dreams are going to be devastated and are going to be shattered.”

Humiliation

Shahed, whose declined to use his real name citing security concerns, lives in Vancouver, British Columbia with his wife and five-year-old son who was born in Canada, who is a citizen.

From 2013 to 2015, Shahed completed his mandatory military service with the IRGC, and was tasked with administrative work, never training in military activities. The experience was deeply degrading, he said.

“The only purpose is just humiliating you, sitting there and cleaning the desk.”

In Canada with a work permit as an on-site engineer, Shahed's permanent residence application has been under review for more than three years.

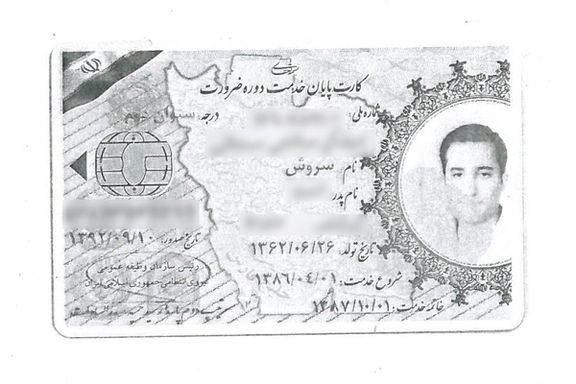

Shahed had officially declared his mandatory military service and provided an ID card indicating the end of his mandatory service in a sworn affidavit reviewed by Iran International.

But he received and official letter saying immigration officers had “concerns surround your membership to the IRGC.”

“Based on your previous membership to the IRGC, I have reasonable grounds to believe you may be inadmissible to Canada ... (based on) membership in an organization that has engaged in subversion or terrorism,” the letter said. Shahed has responded protesting his innocence but has yet to hear back from authorities.

“Every day I have to deal with the stress when I wake up and be prepared that today I could be inadmissible and would have to leave Canada,” Shahed said. “I am not safe anymore.”

Shahed took part in Canadian protests in support of the 2022 unrest in Iran and fears for his safety if deported back to Iran.

Divorce - a way out?

Iran International spoke to another conscript and his wife over Zoom. They too did not want to be identified for their protection and for the safety of their family in Iran.

Since the designation, their lives are mired in uncertainty.

“This decision by the government is affecting every aspect of our lives,” said Farid's wife Roya. “We feel like prisoners here.”

They are both on an open work permit and applied for permanent residency in 2024, but since the IRGC designation their application has been stuck in security checks.

The married couple said they have decided not to leave Canada to travel or visit family because they fear being barred reentry.

Major life decisions like starting a family and buying a house have all been put on hold. If Farid is deported, they said they will likely get a divorce so his wife can have a life in Canada.

Farid told Iran International he served his mandatory service more than 10 years ago and never took part in military drills but worked in a clerical role at an Iranian bank.

Random process

The process in Iran for selecting conscripts to the various branches - whether for the regular army, the IRGC or law enforcement - is random.

Islamic Republic officials tasked with picking conscripts and officers often select recruits by pointing out young men arrayed in a line in front of them.

Prior to listing the IRGC a terror entity, Canada’s former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had resisted calls to make the designation because of the plight of conscripts.

Activists continued to lobby for the change, arguing that identifying those low-level conscripts was an easy and verifiable task.

The terrorist designation empowers the justice system to prosecute IRGC members who have obtained Canadian citizenship and hold them criminally liable for crimes committed overseas.

On the fourth anniversary of the IRGC's downing of a civilian airliner which killed scores of Canadian citizens and residents, Trudeau said in Jan. 2024 that Canada was looking at a way to punish the group.

“We know there is more to do to hold the regime to account and we will continue our work, including continuing to look for ways to responsibly list the IRGC as a terrorist organization.”

When the official announcement was made, Justice Minister Arif Virani said an individual’s willingness and intent to support the IRGC would be an important consideration under the Criminal Code.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada told Iran International that applications are considered on a case-by-case-basis.

“Conscription, in itself, does not necessarily result in a person being deemed inadmissible to Canada," it said. "The admissibility of individuals will be assessed based on a number of considerations."

Those range from the nature of their role in the IRGC to their level of engagement with the organization, it added.

Sadeq Bigdeli, a Toronto-based lawyer who represents several conscripts, said probably only under ten former conscripts have been deemed inadmissible by courts.

Bigdeli said he submitted a petition for guidelines excepting conscripts and even provided a draft text.

“It's not only unfair, but also basically helping the Islamic Republic by diverting resources from where they should be: the real terrorists."

While IRGC conscripts have declared their service voluntarily, actual IRGC members - whom Bigdeli called "masters of deception" – are likely walking free in Canada.