Iran's Writers Union Says Government Rules By Violence

Iran’s Writers Association (IWA) on the anniversary of November 2019 killings of protesters has said that no one believes the Islamic Republic can be reformed.

Iran’s Writers Association (IWA) on the anniversary of November 2019 killings of protesters has said that no one believes the Islamic Republic can be reformed.

The banned writers’ group said in a statement, “The foundations [of the Islamic Republic] rest on imprisonments, killings and elimination of dissidents, intellectuals and protesters.”

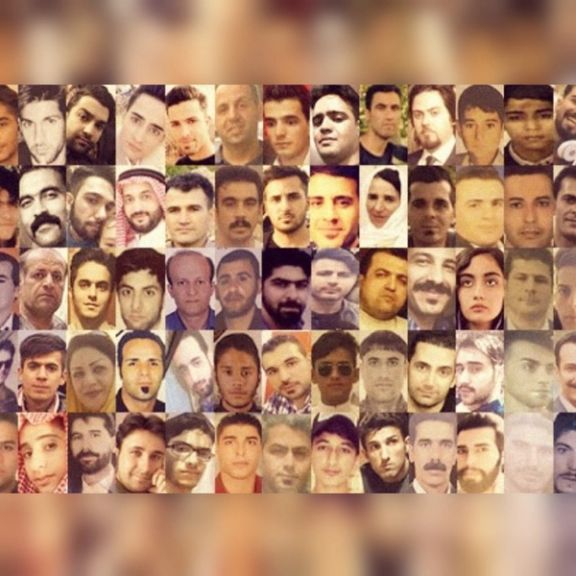

On the second day of widespread protests in mid-November 2019, Iranian security forces opened fire on demonstrators in many cities killing and injuring thousands. Estimates range from 300 to more than 1,500 fatalities. No one has been held responsible and many detained protesters have been tortured and sentenced to prison.

The IWA said that the government has continued persecution of the families of those killed in protests since December 2017, to prevent them from seeking justice. The statement went to say that today even the most optimistic and gullible people have realized that there is no chance for change and reforms.

Members of IWA who meet in secret, having been stripped of their headquarters, also condemned the government for increasing poverty in the country, saying current policies are destroying Iran’s social fabric.

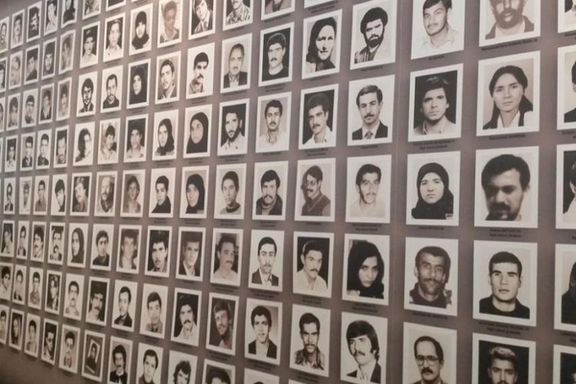

A witness in the Swedish trial of an Iranian over his alleged role in 1988 prison executions has named President Ebrahim Raisi as one of the officials directly involved in the massacre.

The trial of Hamid Noury (Nouri), ex-judicial official, over alleged involvement in Iran’s 1988 prison executions has begun hearings in Albania with testimony on the part played by President Ebrahim Raisi.

The sessions, which started August 10 in Stockholm, moved to Albania to question members of the opposition Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK), who were relocated by the United States after the post-2003 government in Baghdad objected to the presence in Iraq of the armed group, which had been allied to Saddam Hussein.

Six judges, two prosecutors, and the lawyer of 60-year-old Noury all travelled to Duress, Albania. Noury, who was arrested in Sweden in November 2019, is being tried there under a principle of universal jurisdiction and attended Wednesday’s sessions through videoconferencing.

Akbar Samadi, an MEK member, told the court he had been arrested in 1981, aged 14, when a sympathizer of the group. By summer 1988, Samadi had been in prison for seven years serving a ten-year sentence, and Raisi was Tehran deputy prosecutor.

"Raisi … took me to an empty room,” Samadi told the court. “He ordered me to denounce armed uprising. I told him I was shorter than a G-3 battle rifle [a German-made automatic weapon] when I was arrested…Then Raisi told me to denounce a Kurdish party, the Komala, and I protested that I was neither a Kurd nor belonged to the Komala. He got angry and threw me out of the room and sent me to the death corridor.”

Calling out names

Samadi said after being pressed by a commission of interrogators on four occasions he agreed to a televised interview to denounce the MEK. He also alleged that Noury, known as Hamid Abbasi to prisoners, was responsible for calling out victims' names and taking them to be executed.

In his first press conference as president-elect, on June 21, Raisi replied to questions about the 1988 executions that those accusing him were “guilty themselves” and that foreign powers were harboring "17,000 murderers" who had killed Iranian officials, a reference to MEK bombings and other attacks killing Iranian officials and others.

Noury, the only former Iranian official to face trial for the 1988 executions, has denied all allegations and claims he was on paternity leave at the time.

MEK members were the main victims of the 1988 prison executions, with a lower number of executions of leftists. The MEK has claimed 30,000 members died, and in 2019 launched a booklet Crimes Against Humanity naming 5,000.

In 2016, nearly 30 years after the massacres and seven years after his death, the family of Hossein-Ali Montazeri published an audiotape from a meeting with senior judges in which Montazeri condemned the executions. Montazeri, who had been removed as designated successor of then Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini after protesting the executions, said between 2,800 and 3,800 MEK were killed.

Raisi’s election as president in June sparked interest in his role in the executions. Agnes Callamard, secretary general of Amnesty International, immediately demanded that the United Nations Human Rights Council investigate him for crimes against humanity.

United Nations experts on Tuesday called on Iran to repeal a law that restricts abortion and contraception “in direct violation of women’s human rights under international law.”

Iran recently passed a law to boost population growth dubbed as ‘Youthful Population and Protection of the Family’ law, which aims to boost the fertility rate and increase the low population growth rate, well under 2 percent.

UN experts reviewing the law said it is in “clear contravention of international law,” threatening the death penalty for those conducting abortions.

“The consequences of this law will be crippling for women and girls’ right to health and represents an alarming and regressive U-turn by a government that had been praised for progress on the right to health,” the experts said.

Iran’s clerical government has been urging a to achieve a higher population growth rate in recent years as economic hardship and a more educated population have reduced births.

The experts said that instead of repealing laws that discriminate against women or adopting the outstanding yet much needed bill on protection of women against violence, “the Iranian Government is taking further steps to use criminal law to restrict the rights of women.”

Benjamin Weinthal and Alireza Nader argue that academic institutions should consider the background of their faculty members with regards to human rights.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, Iran’s former ambassador to the UN, is complicit in crimes against humanity by using his position as an Iranian diplomat to cover up the 1988 executions of 5,000 dissidents in Iran. Yet that record did not prevent him from securing his PhD in Islamic Studies from McGill University in 2006 and his professorship in religion at Oberlin College in 2007. McGill should revoke his PhD. Oberlin should dismiss him.

An exhaustive 2018 Amnesty International report titled “Blood-Soaked Secrets: Why Iran’s 1988 Prison Massacres Are Ongoing Crimes against Humanity” describes Mallahati as a senior official who helped Iranian leaders actively deny “the extrajudicial executions both in their media interviews and in their exchanges with the UN” in order to insulate the perpetrators from accountability.

Yet the executions were known to the US media and the global public. The New York Times reported in 1988 that Reynaldo Galindo Pohl, the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Iran at the time, “accused Iran of serious human rights violations, including a wave of political executions last summer when Iraq got the upper hand in the war in the Persian Gulf.”

There was overwhelming evidence already in 1988 that Iranian leaders had committed unspeakable crimes in Iran’s vast penal system. When the UN released documents and passed a resolution in 1988 asserting that Iran’s regime carried out mass executions, Mahallati dismissed them as “propaganda,” “fake information,” and “unjust.”

Lawdan Bazargan, the sister of a victim of the 1988 executions, told us: “While Mahallati was enjoying a high-ranking position in an oppressive Islamic regime, my brother was behind bars fighting for human rights and human dignity. Why does a liberal art school such as Oberlin College, which must be the beacon of hope, protect the perpetrators instead of the victims?”

In October 2020, Bazargan and the prominent Canadian-Iranian attorney Kaveh Shahrooz, who lost his uncle in the 1988 bloodletting, tweeted: “In fact, we know that Mr. Mahallati was aware of the killings. Because he is quoted about them in UN reports. But he is quoted as denying and downplaying them. He effectively misled the international community so the killings could continue.”

Mahallati is complicit in other human rights abuses as well. In April, new disclosures by the student paper Oberlin Review show that Mahallati helped lay the ideological foundation for the violent persecution of the Bahai community in Iran. While at the UN in 1983, as the Iranian representative assigned to the UN Commission on Human Rights, Mahallati chargedthe Bahais with terrorism and denied the extrajudicial murders that Tehran committed against them. He also lashed out at the Bahais as “sexual abusers.” Mahallati has not shown a scintilla of regret over his language dehumanizing the Bahai community.

UN and US government reports have long documented the Islamic Republic’s arrests and forced exclusion of Bahais from public life. As far back as 1983, the regime executed 22 Bahais merely for practicing their faith. To this day, the Islamic Republic refuses to recognize the Bahai faith as a religion and tyrannizes its adherents.

McGill’s academic training of Mahallati should not be surprising, as the university has long received donations from Iran. The Alavi Foundation, a regime controlled “charitable” organization in New York, has funded numerous academic and cultural activities in the United States and Canada.

In 2009, US federal prosecutors disclosed that the Iranian government controls the foundation. It began to donate funds to McGill as early as 1987, said Christopher P. Manfredi, provost and vice-principal at the university, in 2013. McGill’s Institute of Islamic Studies took in $270,000 between 2004 and 2010 from the Alavi Foundation. The university was the largest recipient of cash from the foundation in Canada. In 2014, the U.S. government seized a 36-story building in New York owned largely by the foundation, accusing the foundation of hiding its ties to the Iranian government in violation of U.S law.

Mallahati is but one example of former Iranian officials complicit in crimes against humanity who have found employment in Western academia. The regime’s former ambassador to Germany, Seyed Hossein Mousavian, teaches at Princeton University. On Mousavian’s watch as ambassador, the Iranian regime assassinated Iranian-Kurdish dissidents at the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin in 1992.

Mahallati, who sports the moniker “professor of peace” at Oberlin, has blood on his hands. It is time that both Oberlin College and McGill University take action.

Alireza Nader is a senior fellow focusing on Iran and US policy in the Middle East at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), where Benjamin Weinthal is a research fellow. Follow them on Twitter @AlirezaNader and @BenWeinthal. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, nonpartisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.

The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of Iran International.

A hardline member of Iran's parliament has tried to deny a report that he had bragged about killing protesters in 2019 and saying no one would arrest him.

Lawmaker Hassan Norouzi told the parliamentary news service Monday he had not made remarks attributed to him Sunday by Didban-e Iran website over the 2019 protests when hunreds were killed by security forces.

Norouzi said a “fake reporter” had called him and asked about the ‘Iran Atrocities Tribunal’ held in London last week. But Didban-e Iran defended its report, insisting it had taped the conversation and might sue the deputy.

Norouzi allegedly told the website: "I was one of those who shot people. [Yes,] we killed people… They had set fire to banks and we killed them. Who is going to put us on trial for it?" He then allegedly said was "joking" and hung up.

The comments, as reported, drew swift condemnation. The conservative newspaper Jomhouri Eslami wrote that “such a joke” was “deplorable by anyone, but even more by you who are a cleric wearing the cloak of the Prophet of Mercy [Muhammad].” The newspaper argued that Islamic values required those setting fire to banks to face justice and a proportionate punishment rather than being killed before a crime was proved.

Human rights lawyer Ali Mojtahedzadeh, in a commentary published by Didban-e Iran Monday, noted that Norouzi was a member of the parliament's Legal and Judiciary Committee, making his statements "even more deplorable.”

"What kind of a joke can this be when according to official figures nearly 300 people died in this incident, many more were wounded or detained, and so many lives were ruined?" Mojtahedzadeh asked. He criticized parliament and judiciary for not carrying out "a minimum level of investigation" after two years. "Which legal system in the world doesn't charge even one person for the murder of at least 300 citizens in the streets in broad daylight?” he asked.

Iran has not officially announced figures for deaths or arrests, nor put anyone on trial for killing protesters, but has prosecuted and passed heavy sentences including the death penalty on protesters on charges including “assembly and collusion against the regime.” Officials have put the number at over 200. Independent reports have put the number of protesters killed between 300-1,500.

Mojtahedzadeh claimed Iran had laws forbidding security forces shooting suspects above the waist in any situations and that shooting anyone, even if they were setting fire to banks, needed strong justification: "The real tragedy is that not only justice, based on Sharia and the law, has not been served in the case of these events but also some truths are being distorted and even mocked."

A video posted on social media by ‘mothers of victims’ challenged Norouzi to “stop hiding in your lair with 30 bodyguards” and to “come out and face us.”

The ‘Iran Atrocities Tribunal’ claimed in a Tweet Saturday that Iran’s deputy foreign minister Ali Bagheri-Kani had threatened to “stop part” of Iran’s discussions with world powers if London did not stop the tribunal meeting. The tweet claimed the tribunal, which purports to be quasi-judicial investigation into the November 2019 protests, learnt this from “European sources.”

Didban-e Iran's report Saturday also claimed its “informed sources” had said the foreign ministry had protested to the British government for allowing the tribunal be held in the UK.

A court in Iran has sentenced a retired female teacher who had signed a letter demanding Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s resignation to a five-year prison term.

Nosrat Beheshti, who is also a civic and labor activist along with 13 other women activists published a letter in August 2019 calling on Khamenei to step down. Most were detained later, and some sentenced to long prison terms. Prior to that, 14 men had also issued a letter making the same demand, most of whom were later detained.

The Intelligence Ministry arrested Beheshti in July this year and she has remained in detention. A "Revolutionary Court" in Mashhad issued her sentence.

Prosecutors accused her of “Propaganda against the regime” and “Activities against national security”. She has also been accused of “Marxist propaganda in classrooms” while she retired eight years ago.

While Khamenei in the past has insisted that citizens can criticize him, the slightest remark can land journalists or ordinary people in jail. Typical charges include propaganda against the regime or insulting the Supreme Leader.