More Stories

Freelancers across Iran lost foreign contracts and saw income dry up during January’s internet shutdown, digital workers told Iran International, as weeks offline cut their access to projects and payments in an economy already hit by global isolation.

Iran’s internet, throttled for 20 days during January’s mass killing of protesters, has been restored since earlier this month, but remains unstable, with VPNs and other censorship-bypassing tools now far harder to access than before the shutdown.

“The internet is not stable enough for me to confidently take on projects, and transferring money has become so complicated that the losses outweigh the income,” one electrical engineer working as a freelancer told Iran International, speaking on condition of anonymity for security reasons.

Iranian entrepreneurs and freelancers are mostly shut out of global platforms and payment systems due to US sanctions, forcing them to depend on expensive workarounds that put their businesses at risk.

The engineer said that before the shutdown, earnings depended on the size and complexity of each contract.

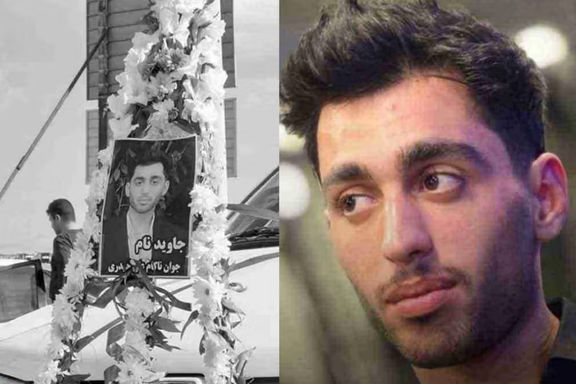

Ali Heydari, a 20-year-old Iranian protester wounded and arrested during demonstrations in Mashhad on January 8, was shot in the head and killed in detention about a month later, a source close to his family told Iran International.

Heydari was injured by live ammunition in his leg during protests on January 8 and taken away alive by security forces. After 33 days of complete silence about his whereabouts, his body was handed to his family on February 9.

Authorities told his father by phone that his son had “died during the protests” and that his body had been kept in morgue for over a month.

Family members who saw the body dispute that account.

They told Iran International that signs of severe beating, a broken nose and, most critically, a bullet wound to the left side of his forehead indicate he was tortured during detention and later killed with a close-range shot to the head.

Two additional visible signs, they said, strongly suggested that only days – not weeks – had passed since his death.

Live fire and arrest

Heydari was born on March 27, 2005, in the village of Virani in Shandiz and lived in Mashhad. He worked in a woodworking shop. Had he not been killed in mid-February, he would have turned 21 within weeks.

On the evening of January 8, he joined thousands of others protesting on Haft-e Tir Boulevard in Mashhad. Witnesses said security forces began firing at crowds gathered near the local police station around 9 p.m.

A protester who survived the crackdown told Iran International that a live round struck Heydari in the leg early in the shooting.

“He lost balance and fell. There was heavy bleeding. We couldn’t pull him back,” the witness said. “Security forces reached him, lifted him and dragged him away.”

Heydari’s mobile phone fell from his pocket as he collapsed. The witness retrieved it before fleeing.

33 days of enforced disappearance

From the moment of his arrest until the early hours of February 9, his family received no official information about his location, medical condition or legal status.

After learning from the witness that Heydari had been wounded and detained, the family searched for him across hospitals, detention centers, courts and morgues. Authorities – including the Intelligence Ministry, the Revolutionary Guards’ intelligence unit and local police – denied knowledge of his case.

The systematic denial of information about a detainee seized in plain sight amounts to enforced disappearance under international law. In practice, it left the family in prolonged uncertainty, cut off from any legal recourse and unaware of whether he was alive or dead.

Such denial also removes scrutiny – a condition that rights groups say can facilitate torture and extrajudicial killing.

The call from the morgue

In the early hours of February 9, officers from the investigative unit in the Shandiz area phoned Heydari’s father and instructed him to go to the Behesht-e Reza cemetery in Mashhad to identify and collect his son’s body.

When the father asked what had happened, he was told his son had “died during the protests” and that his body had been in morgue for more than a month.

Family members who viewed the body said there were visible bruises and a fractured nose, consistent with severe beating. The gunshot wound to the forehead, they said, appeared to have been fired from close range, likely with a handgun.

They also pointed to physical details suggesting that Heydari had been alive long after his January 8 arrest. He had visited a barber that Thursday and had only faint stubble at the time of his detention, they said, but facial hair had grown noticeably by the time his body was returned. They added that the body’s condition did not align with a death that had occurred a month earlier.

Together, they say, these signs contradict the official explanation and indicate he was killed days before his body was released.

Burial under watch

Heydari was buried in his hometown of Virani. The funeral drew large numbers of residents, alongside a significant presence of plainclothes security agents.

Agents attempted to detain several participants during the burial but were prevented by resistance from mourners, according to attendees. The following day, security forces warned the family against holding a memorial ceremony. The gathering ultimately proceeded after mediation by relatives.

Silence and risk

Shahram Sadidi, a Mashhad-born political activist based in the UK who first publicized Heydari’s disappearance, told Iran International that public unawareness may have made it easier for authorities to act without scrutiny.

“If news of his detention had spread earlier, public pressure might have prevented this outcome,” he said.

Field reports, Sadidi said, indicate that more than a thousand people – possibly several thousand – were detained in Mashhad during and after the January 8 protests, with little information released about most of them.

“Families are often threatened that speaking out will harm their loved ones,” he said. “Fear keeps many silent, and that silence creates space for abuse.”

Heydari’s case, marked by live-fire injury, disappearance and a fatal gunshot in custody, underscores the risks facing detainees held beyond public view – and the consequences of 33 days in which no authority acknowledged where he was.

The night air on Jan. 8 in northeastern Tehran filled with chants rising in defiance. Among them stood Pooya Faragerdi, a violinist whose life was measured in music and a heart that beat for Iran. Then came the gunfire.

Faragerdi, 44, was shot by security forces near a police station in Pasdaran that night.

Videos verified by Iran International from Pasdaran on Jan. 8 showed wounded protesters lying bloodied on the street as others tried to help, with gunfire audible in the background.

Senator John Kennedy on Wednesday defended Trump's Iran negotiations, citing a measured Venezuela-style strategy and doubts about Tehran's sincerity despite the talks.

"President Trump made a promise to Iranian people to support them... The president is in the process to keep his promise," Republican Senator from Louisiana told Iran International.

Kennedy said US decisions on dealing with the Islamic Republic will rely on Israeli intelligence assessments, adding the need for a careful strategy rather than hasty actions like bombing or deploying thousands of American troops.

"You can't just go in and start dropping bombs and committing thousands of American troops that could make things worse. You have to be strategic about this like we were in Venezuela," he added.

Iran International has obtained information alleging that senior Iranian diplomats transported large amounts of cash to Beirut in recent months, using diplomatic passports to move funds to Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

The transfers involved at least six Iranian diplomats who carried suitcases filled with US dollars on commercial flights to Lebanon, according to the information.

The cash deliveries formed part of efforts to help Hezbollah rebuild its finances and operational capacity after sustaining significant blows to its leadership, weapons stockpiles and funding networks.

Those involved include Mohammad Ebrahim Taherianfard, a former ambassador to Turkey and senior Foreign Ministry official; Mohammad Reza Shirkhodaei, a veteran diplomat and former consul general in Pakistan; his brother Hamidreza Shirkhodaei; Reza Nedaei; Abbas Asgari; and Amir-Hamzeh Shiranirad, a former Iranian embassy employee in Canada.

Taherianfard traveled to Beirut in January alongside Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi. He carried a suitcase filled with dollars, relying on diplomatic immunity to avoid airport inspection.

Similar methods were used on other trips, with diplomats transporting cash directly through Beirut’s Rafik Hariri International Airport.

Ali Larijani, secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, also traveled to Beirut in October and carried hundreds of millions of dollars in cash, according to the information.

After Israeli strikes disrupted weapons and cash-smuggling routes used by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards in Syria, Beirut airport emerged as a primary channel for direct cash deliveries.

Hezbollah’s longstanding influence over security structures at the airport has in the past facilitated such transfers, though Lebanese authorities have recently increased control.

The cash shipments come as Hezbollah faces acute financial strain. The group has struggled to pay fighters and to finance reconstruction in parts of southern Lebanon heavily damaged in fighting. Rebuilding costs have been estimated in the billions of dollars.

In January 2025, The Wall Street Journal reported that Israel had accused Iran of funneling tens of millions of dollars in cash to Hezbollah through Beirut airport, with Iranian diplomats and other couriers allegedly carrying suitcases stuffed with US dollars to help the group recover after major losses.

Israel filed complaints with the US-led cease-fire oversight committee, while Iran, Turkey and Hezbollah denied wrongdoing. The report said tighter scrutiny at Beirut airport and the disruption of routes through Syria had made such cash shipments a more prominent channel for funding.

On Tuesday, the US Treasury announced new sanctions targeting what it described as key mechanisms Hezbollah uses to sustain its finances, including coordination with Iran and exploitation of Lebanon’s informal cash economy.

The Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned Lebanese gold exchange company Jood SARL, which operates under the supervision of US-designated Al-Qard Al-Hassan, a Hezbollah-linked financial institution. Treasury said Jood converts Hezbollah’s gold reserves into usable funds and helps the group mitigate liquidity pressures.

OFAC also sanctioned an international procurement and commodities shipping network involving Hezbollah financiers operating from multiple jurisdictions, including Iran.

“Hezbollah is a threat to peace and stability in the Middle East,” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said in a statement, adding that the United States would continue working to cut the group off from the global financial system.

Iran has long considered Hezbollah a central pillar of its regional alliance network and has provided the group with financial, military and logistical support for decades.