Since then, the US military presence around Iran has expanded steadily, and many Iranians openly call for American military action against the Islamic Republic.

Yet some of Trump’s advisers draw cautionary parallels between a potential strike on Iran and the US invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003, warning against another protracted and costly war.

There is, however, another Middle Eastern precedent—one that both Iran and the United States would be wise to examine closely: the 1991 Shia and Kurdish uprising in Iraq. It was a revolt sparked in part by American encouragement but crushed after the United States did not intervene on behalf of the protesters.

US call for uprising

On Feb. 15, 1991, President George H.W. Bush called on “the Iraqi military and the Iraqi people to take matters into their own hands and force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside.”

His message was broadcast into Iraq via television and radio. Coalition aircraft dropped leaflets urging Iraqi soldiers and civilians to “fill the streets and alleys and bring down Saddam Hussein and his aides.”

The call came weeks after the US-led coalition had launched its campaign to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait. Shia communities in southern Iraq and Kurdish groups in the north rose up against Saddam.

The uprisings were fueled by deep public anger over Saddam’s military adventurism — from the long war with Iran to the invasion of Kuwait — which had imposed immense human and economic costs on Iraqi society.

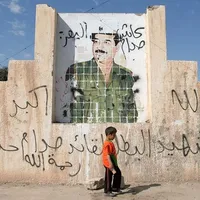

Protests began in Basra and quickly spread to Najaf, Karbala and Nasiriyah. Shia rebels and defecting soldiers attacked security forces and government buildings. Baath Party offices were seized, officials were killed, prisoners were freed.

Within roughly two weeks, 14 of Iraq’s 18 provinces were effectively outside the central government’s control.

It was a dramatic advance — but it did not last.

The collapse of the uprising

The rebellion ended in one of the bloodiest crackdowns in modern Iraqi history. Its failure stemmed from a combination of factors: American hesitation to intervene, Saddam’s extensive use of force and deep divisions among the opposition — a combination that could, in a different form, reappear in Iran.

Despite overwhelming military superiority in the Persian Gulf, the Bush administration chose not to enter a new confrontation with Saddam. There were fears of “another Vietnam,” with American troops drawn into a prolonged deadly conflict.

Bush publicly called for Saddam’s removal but remained wary of what might follow. One concern was the “Lebanonization” of Iraq — the prospect of the rise of Iranian-backed Shia forces in Baghdad.

Meanwhile, opposition groups inside Iraq — Shia factions, Kurds, nationalists and others — failed to unify under a coherent command structure. The opportunity to conquer Baghdad slipped away.

The Gulf War ceasefire allowed Saddam breathing room. A regime many believed was on the brink of collapse recovered quickly. Relying on the Republican Guard — which had remained in the war largely intact — Saddam launched a counteroffensive.

Although parts of Iraq were placed under no-fly zones, Saddam exploited a loophole: helicopters were not barred. He used them to attack rebels, and coalition forces did not intervene to stop those assaults.

The Republican Guard shelled residential neighborhoods indiscriminately, conducted house-to-house arrests and carried out mass executions. Chemical weapons were used against some rebel-held areas. Even those who sought refuge in religious shrines in Najaf and Karbala were not spared.

Estimates suggest that between 30,000 and 60,000 Shia in the south and around 20,000 Kurds in the north were killed. Roughly 2 million people were displaced.

Lessons for the US and Iran

The Iraqi uprising offers several lessons for policymakers in Washington, and for Iranians.

First, the international community often underestimates a regime’s capacity for internal violence. Military weakness abroad does not necessarily translate into fragility at home.

A government that perceives its survival to be at stake may show restraint toward foreign adversaries while unleashing far harsher tactics domestically. Even an army battered in external war can regroup internally, close ranks and act with renewed intensity.

Saddam’s regime had been defeated by an international coalition, yet it retained loyal security structures, a functioning chain of command and the willingness to use extreme force against its own citizens.

At such moments, any external concession or diplomatic maneuver can be repurposed as an instrument of internal consolidation.

A deal with Iran could give the ruling elite a chance to regroup and unleash a new wave of repression against its own people.

For opposition movements, strategic cohesion matters. Agreement on minimum political goals, unity of command and preparation for a potential power vacuum can be decisive.

Victory does not arrive simply because a regime appears weakened. In Iraq, rebels went so far as to appoint local governors in areas they controlled — but the new order collapsed swiftly. Divisions within the opposition ultimately strengthened the existing power structure at a decisive moment.

At the same time, global leaders should recognize that threats alone are insufficient. If a foreign power seeks to alter the balance of power, it must understand that displays of force without the intention to use it can carry profound and unintended consequences.