A man, a dog, and a private wish turned public tragedy in Iran

Weeks after Iran’s bloody January crackdown, intimate tragedies are emerging from the silence, among them the story of a young auto mechanic and his dog.

Iran International

Weeks after Iran’s bloody January crackdown, intimate tragedies are emerging from the silence, among them the story of a young auto mechanic and his dog.

Ali Karami, 26, who was shot and killed by Iran’s security forces on January 8, had one wish: “If I die before my dog,” he said, “let her see my lifeless body.”

He said it in a video posted to Instagram in October 2024, narrating as he played tug-of-war with his dog, Ariel—laughing, absorbed in an ordinary moment of life.

After his death, the video spread widely across Iranian social media, capturing the public imagination as viewers returned to his words with disbelief.

Karami believed dogs understand death, and that without seeing him, she might think he had simply abandoned her.

He may have contemplated the possibility of dying young, but not like this—not shot in the street, his private reflection transformed into a national elegy.

Karami was an auto repair mechanic and a devoted dog lover who rescued stray animals. Originally from Kermanshah Province, in the country’s Kurdish region, he later moved to Tehran for school and work.

His Instagram account, @alikaramiservis, offers a window into his daily life—his pride in his craft, his affection for dogs, and his love of nature and music, including the songs of Dariush Eghbali.

It is also a record of one of the tens of thousands of people who took to the streets demanding freedom and were met with bullets.

Karami was reportedly trying to protect an elderly woman when he was shot and killed.

In many of his photos, Ariel—the dog he referred to as his daughter—is never far from his side. They play ball, cook, or simply share quiet time at the repair shop: fragments of an unremarkable, joyful life.

“She understands death,” Karami says in the October video. “If she does not see my lifeless body, she will think I abandoned her and will keep waiting for me to come back.”

“That’s a friendship without limits,” he adds. “Pure loyalty.”

Karami’s final post, dated December 30, shows him proudly displaying his work: a car he had restored at Sehand Car Clinic in Tehran.

From February 8 onward, the account appears to have been run by family members or friends. That day, they posted a tribute video showing Karami dancing, exercising, and spending time with Ariel. They also reposted the October video—his voice now echoing with an unintended prophecy.

This time, there was an ending.

The final images show Ariel lying at Karami’s gravesite.

Just as he had asked.

In the most tragic way, a fate he once spoke of—unknowingly—was fulfilled.

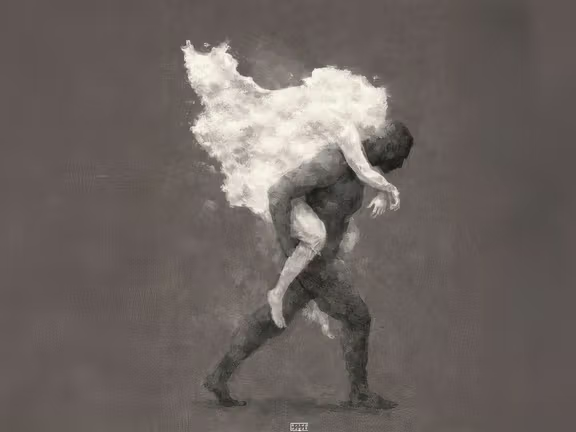

Digital art and AI-generated images of protesters killed in Iran have flooded social media, turning victims of recent unrest into national icons.

While the identities of many remain unconfirmed, the stories behind these images have helped create a shared narrative for a public mourning thousands of deaths during just two days of crackdown on Jan. 8 and Jan. 9.

In the weeks since, artists have used technology to blend modern tragedy with Persian mythology. These digital tributes often place fallen protesters in settings reminiscent of the Shahnameh, Iran’s national epic, lending the dead a sense of timeless honor.

The firefighter

One of the most widely shared figures is Hamid Mahdavi, a firefighter from the northeastern city of Mashhad, who was killed on Jan. 8 after being shot in the throat.

Social media posts and witness accounts say Mahdavi spent his final hours carrying wounded protesters away from lines of security forces. Digital artists have reimagined him as a guardian figure.

Videos circulating online show a man carrying the injured, but activists say it is difficult to confirm with absolute certainty whether the person in the footage is Mahdavi. For those mourning, however, the image has become inseparable from his story.

The firefighter from Mashhad is now widely seen as a symbol of rescue.

“He was brave, kind and honorable,” one user wrote in Persian on Instagram, where Mahdavi had been active before his killing. “His memory will remain eternal.”

Another wrote: “I’ve watched this video a hundred times and I still cannot stop crying.”

The man as shield

In another story that has become central to the narrative of the January uprising, a man identified by social media users as Mohammad Jabbari, or “Mohammad Agha,” is reported to have died while protecting others.

In a video that has gone viral, a man is seen holding open a building door to let protesters inside for safety, then attempting to force it shut against advancing security agents.

According to activist accounts, agents shot the man at close range after forcing their way through. Digital artists now depict him as a literal shield, with some comparing the scene to moments from the Shahnameh.

While the man’s identity cannot be verified with certainty, the narrative of “the man at the door” has taken on powerful symbolic meaning as an act of self-sacrifice.

Social media comments reflect a deep emotional connection to the scene.

“One day we will see this statue standing in the heart of Tehran,” one person wrote. Others simply posted, “Hold the door,” a phrase that has become shorthand for the act shown in the footage.

“These symbols must be built in our Iran so that future generations remember their history,” another user commented.

Shared memory for the future

The use of AI and rapidly produced digital art has allowed Iranians to create a visual record in real time.

As the government restricts traditional media and periodically shuts down the internet, these images offer a way to preserve stories the state cannot easily erase.

“We do not know the names of everyone who fell,” one user wrote beneath a viral tribute. “But these images carry the meaning of what happened. They are the glue that holds our story together.”

By focusing on individuals like Mahdavi and the man at the door, the protest movement has moved beyond statistics. Even when identities remain unconfirmed, the images ensure that stories of resistance continue to circulate—inside Iran and beyond it.

The killings that swept Iran last month revived memories of 1988, when the Islamic Republic erased thousands of political prisoners in silence—my brother, Bijan, among them.

While the world may see in the staggering death toll of the January protests an unprecedented explosion of violence, those of us who have spent decades seeking justice see something else: the chilling continuity of a regime that has only ever known one way to survive.

For us, the massacre of thousands of unarmed protesters is not a breakdown of the system. It is the system functioning exactly as designed.

The parallels with 1988 are as deliberate as they are haunting.

Back then, the Islamic Republic imposed a total information blackout. Prison doors were bolted. Phone lines were cut. Family visits were suspended without explanation. Families were left in torturous limbo, wandering from prison gates to government offices, met only with silence or lies.

Months later, the truth emerged in the most brutal form: a bag of personal belongings handed to a father, an order not to mourn, and the realization that a loved one was gone.

Today, the regime replicates that silence through digital darkness—a nationwide internet shutdown. But the scale has shifted. In 1988, authorities could intimidate families one by one. They ordered us not to hold funerals, not to cry, not to tell our neighbors. They believed that by hiding the bodies, they could hide the crime.

In 2026, the numbers are too large for secrecy to hold. When the reported death toll reaches 30,000 in a single week, grief becomes a tidal wave no blackout can contain. Familiar tactics of intimidation—extorting “bullet fees,” abducting the wounded from hospital beds, desecrating graves—no longer work as intended.

In 1988, the regime hid its atrocities beneath the soil of Khavaran. In 2026, in an unimaginable cruelty, it staged its terror in the open.

Videos that surfaced despite the shutdown shattered the nation: hundreds of lifeless bodies sealed in black plastic, lined along sidewalks and outside gray buildings like discarded refuse. Families were forced to walk these endless rows, performing a sadistic ritual of identification.

In one widely shared clip, a father’s voice trembles as he searches, calling out, “Sepehr, my son—my Sepehr, where are you?”

For decades, the Mothers of Khavaran—mothers, fathers, siblings, and children—refused to surrender to silence. They were the first to turn grief into political defiance. They wore white to funerals and memorials, rejecting the regime’s imposed black, the color of official sorrow.

White declared innocence. White rejected the legitimacy of the executioners.

They clawed at the dirt of Khavaran with bare hands, searching for truth even as Revolutionary Guards beat them and trampled their flowers.

That spirit has not vanished. It has evolved.

What we see today—mothers dancing at their children’s graves, distributing sweets instead of halva, clapping instead of wailing—is not denial. It is defiance. It is a refusal to allow a theocracy that has weaponized martyrdom for nearly half a century to dictate how death is understood. As one mother put it, our hearts are broken, but our spirits will not bend.

In 1988, impunity—enabled by an international community eager to close the Iran-Iraq war through UN Resolution 598—convinced Tehran that mass murder was an effective tool of statecraft.

Iran in 2026 is different. The world is watching in real time. The “Nuremberg moment” long urged by human-rights lawyers is no longer aspirational. It is necessary.

My brother Bijan and the thousands murdered in the dark summer of 1988 were denied even the pretense of justice: no trials, no headstones, no place in official history.

The Islamic Republic believed it was burying bodies. It was planting seeds.

Those seeds have now erupted. The legacy of the fallen is not buried in the mute soil of Khavaran; it lives in every young Iranian who stands firm before gunfire. We are no longer merely archivists of the dead. We have come to demand accountability.

History has never wavered on this truth: no tyranny is eternal. Their gallows will not save them from the dawn.

Hundreds of messages sent to Iran International from Iranians inside the country urge US President Donald Trump not to negotiate with the Islamic Republic, warning that talks would legitimize repression and betray protesters killed by security forces.

The messages from people inside Iran appeal directly to Trump to abandon diplomacy and instead support what they describe as a nationwide struggle for freedom and democracy.

“If you want to help the people of Iran, what does negotiating with our enemies mean?” one message from Tehran said, adding: “Negotiations with this regime only buy time for repression.”

Other messages from inside Iran cite recent protests and the deadly response by security forces, saying negotiations would legitimize a government they say has blood on its hands.

“Negotiating with this clerical government means trampling on the blood of young people killed in the streets,” one message reads.

Messages received from the city of Qazvin warn that talks would demoralize protesters and undermine months of resistance. “We came to the streets to free Iran from these criminals,” one message said. “Trading with this regime is trading with the blood of the people.”

Several messages from Tehran reference Trump’s past statements and promises, saying many Iranians trusted his rhetoric about standing for freedom.

“You said you support liberty,” one message from Tehran reads. “Please be the voice of the Iranian people. We are dying in the streets for freedom.”

A message sent from Iran’s southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan offers condolences to families of those killed and urges Trump to “stand with the Iranian nation, not the Islamic Republic.”

Other messages from inside Iran warn of what they describe as a long pattern of deception, saying past deals with Iranian authorities helped ease international pressure on the Islamic Republic even as repression continued at home.

Some messages stress that the protest movement will endure even without foreign assistance. “Even if there is no outside intervention, we will stand together,” one message says.

'Not our representatives'

Across the messages, a shared demand emerges that world leaders not view the Islamic Republic as representing the Iranian people and avoid negotiations that could confer legitimacy on it.

“Please negotiate with the brave people of Iran, not with this suppressive regime,” one message says. “Do not turn a blind eye to these crimes.”

“Tell Trump that no one negotiates with a killer; killers should only be punished,” another message said.

Middle East analyst Elizabeth Tsurkov says people close to President Trump believe he is likely to strike Iran, arguing the Islamic Republic’s failure against Israel revealed a “paper tiger” abroad — even as it remains ruthlessly lethal toward its own citizens.

Speaking to Iran International in Washington, Tsurkov, a senior non-resident fellow at the New Lines Institute, said the recent US military buildup in the region is the largest since the 2003 invasion of Iraq and has raised expectations that force may ultimately be used.

“People who know the president personally have told me they believe he will attack,” she said, adding that talks are unlikely to succeed because “the maximum that the Iranian regime is willing to offer is less than what the US is willing to accept.”

Talks between Iran and the United States were held on Friday, with multiple back-and-forth exchanges taking place both through an Omani mediator in Muscat and reportedly in face-to-face meetings.

Iran’s foreign ministry spokesman said the talks concluded with an agreement to keep negotiations going, after both sides outlined their positions.

'Paper tiger'

Tsurkov said Iran’s performance in its June conflict with Israel underscored the limits of its ability to harm a capable adversary.

“Iran was doing their best to kill Israelis and damage infrastructure, but killed around 30 people and failed to hit targets that could have altered the conflict, such as facilities producing air-defense missiles,” she said. “Israel, by contrast, destroyed missile production sites and struck nuclear facilities inside Iran.”

"I think after the 12-days war with Israel, uh, there's a uh um there's a term was coined that they are paper tigers... they are a paper tiger to the outside world."

The United States held five rounds of negotiations with Tehran over its disputed nuclear program last year, for which Trump set a 60-day ultimatum.

When no agreement was reached by the 61st day, Israel launched a surprise military offensive on June 13, followed by US strikes on June 22 targeting key nuclear facilities in Isfahan, Natanz and Fordow.

Hundreds of military personnel and civilians were killed in the Israeli airstrikes. Tehran responded by launching more than 500 ballistic missiles and 1,100 drones, killing 32 Israeli civilians and one off-duty soldier and causing widespread damage.

A ceasefire ended the 12-day conflict, but the fate of nearly 400 kilograms of near weapons grade enriched uranium is still unknown. Tehran has said it will not give up the uranium stockpiles.

Tsurkov, who was held from 2023 to 2025 by Iran-backed militias in Iraq, said the conflict exposed a familiar pattern.

“The militias in Iraq pose a significant threat to the Iraqi people. They have killed thousands of innocent Iraqis, Shia and Sunni,” she said.

“They’ve killed only a couple of Israelis with a drone attack. The same with the Iranian regime: it managed to kill around 30 Israelis and really did try to kill more. But when it comes to the Iranian people, when you are facing unarmed protesters, you can just mow them down and kill tens of thousands in the span of about two days.”

‘Desperate protesters’

Tsurkov said the Islamic Republic is now in an “extreme moment of weakness,” pointing to reports that Tehran may be willing to negotiate not only over its nuclear program but also over missiles and proxy militias.

“Iranians have tried voting, only to see elections forged. They have tried peaceful protest and were slaughtered,” she said. “When all avenues are closed, people either leave or become radicalized.”

Last month, Iran International reported that more than 36,500 Iranians were killed by security forces during the January 8–9 crackdown on nationwide protests, making it the deadliest two-day protest massacre in the country’s history.

“When people love their country but still hope foreign powers will bomb it just to free them, that is the clearest sign of utterly failed leadership,” Tsurkov said.

“The solution to the suffering of Iranians and to the security threats that emanate from Iran is the end of this regime,” she said. “It is not easy and it will not happen quickly, but that should be the goal guiding policy.”

Human rights activists are sounding the alarm over reports of secret and extrajudicial executions in Iran, warning that the authorities may be moving toward retaliating against detainees after the deadly crackdown on protests in January.

Domestic accounts—fragmentary and difficult to verify under heavy censorship—suggest that killings may be continuing beyond those reported during the nationwide unrest of January 8 and 9, when security forces opened fire on demonstrators in cities across the country.

One case frequently cited by rights activists involves Mohammad-Amin Aghilizadeh, a teenager detained in Fooladshahr in central Iran.

According to activists who followed the case, judicial authorities initially demanded bail for his release. Days later, his family was instead given his body, bearing signs of a gunshot wound to the head.

In another case, Javad Molaverdi was wounded by pellet fire during protests in Karaj, detained by security forces, and transferred to Ghezel Hesar Prison. His family later discovered his body in a cemetery, rights activists said.

Such cases have prompted warnings from international monitors. The United Nations special rapporteur on Iran, Mai Sato, has said she is closely following reports suggesting that executions and deaths in custody may be used to instill fear.

‘Doesn’t add up’

One of the most striking accounts received recently by Iran International comes from a journalist inside the country who described a conversation with a ritual washer working at a cemetery in Tehran province.

The journalist met the worker on January 27 and described him as visibly shaken, despite years of professional exposure to death. The washer told the journalist that the official reports “didn’t add up” for some bodies delivered to the cemetery.

“They bring a body that was clearly killed less than two days ago,” the worker said, “but say it has been in storage for 15 days because it was unidentified.”

“We have seen every kind of body for years—traffic accidents, heart attacks,” the worker added. “We can tell the difference. We know.”

Professionals working in forensic medicine and cemetery washing facilities often develop, over time, the ability to estimate time of death based on physical signs, even without laboratory tools.

Worrying precedents

The significance of the testimony lies not only in its emotional impact but in what it suggests about discrepancies between official explanations and physical evidence.

Such accounts cannot, on their own, establish a nationwide pattern. But taken together with reported cases of deaths in custody, they have intensified fears among activists that the authorities may be sending a broader message to protesters: that survival is no longer assured once dissent reaches detention centers.

Those fears are shaped in part by historical precedent.

Documented cases of extrajudicial killings in Iranian prisons—most notably in the early years after the 1979 revolution and during the 1988 mass executions—have heightened sensitivity to any signs that repression may again be moving out of public view.

The evidence gathered so far remains incomplete and uneven. But rights activists say it is sufficient to raise serious concern that deaths in custody and quiet executions may be occurring after protests have been suppressed.