More Stories

The editor of Iran’s hardline Kayhan newspaper dismissed the ongoing protests on Wednesday, criticizing government remarks that described demonstrations as legitimate expressions of public pressure.

Hossein Shariatmadari, Kayhan’s editor-in-chief appointed by the Supreme Leader, wrote that the protests did not deserve to be heard, arguing they were driven by what he described as foreign-linked agitators rather than economic grievances.

He took aim at comments by government spokesperson Fatemeh Mohajerani, who had said authorities recognize peaceful protests and should listen when people raise their voices under economic pressure.

Shariatmadari said that protest slogans did not reflect economic demands and alleged that demonstrators had expressed support for what he called “killers” of Iranian citizens, accusations frequently leveled by hardline media against dissent.

A Tehran bus workers’ union said on Wednesday it supports public protests, arguing that citizens have the right to demonstrate against economic pressure, repression and structural corruption.

In a statement, the Syndicate of Workers of Tehran and Suburbs Bus Company said disadvantaged people are entitled to take to the streets in response to what it described as repressive policies and government actions that have harmed livelihoods.

“The deprived people have the right to protest against repressive policies, the state’s attack on public livelihoods, structural corruption and widening class gaps,” the union said.

Protesters gathered in the cities of Isfahan and Kermanshah on Wednesday, according to videos received by Iran International, as demonstrations continued across multiple parts of Iran.

Footage from Isfahan showed groups of people assembling at Naqsh-e Jahan Square, one of the country’s most prominent public spaces and a recurring site of protest during periods of unrest.

Separately, video from the western city of Kermanshah showed demonstrators holding a protest and chanting “death to the dictator,” a slogan commonly used in protests critical of Iran’s leadership.

Iran’s bazaar strike, sparked by currency chaos and collapsing purchasing power, is widening beyond traders and shopkeepers – pulling in students and salaried workers as the anger is spreading across Iran’s squeezed middle and low-income households.

President Masoud Pezeshkian’s administration says it recognizes the public’s right to protest, but it has neither the financial resources to placate the deepening public anger nor the political leverage to confront hardliners who place the blame squarely on the government.

Pezeshkian addressed the situation on social media on Tuesday, writing that people’s livelihoods are his daily concern and that fundamental reforms of the monetary and banking system are on the agenda to protect purchasing power. He also said he had tasked the interior minister with speaking to representatives of the protesters.

The message failed to convince most Iranians, including many of Pezeshkian’s own supporters.

Morteza Nemati Zargaran, a university professor, reminded Pezeshkian in a post on X that recognizing public protests carries no practical guarantees as long as he lacks the necessary authority.

“What action can you take if the protesters’ representatives challenge the country’s overarching policies – policies to which you have repeatedly declared your loyalty? And what will you do if … they are arrested by power centers beyond your government?”

'Closed is cheaper than open'

The economic strain has been especially visible in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar.

Morteza, a 45-year-old former wholesale shoe merchant who recently closed his shop after failing to pay rent, told Iran International that nearly all his fellow traders have joined the ongoing bazaar strike.

“They tell me I’m lucky I shut my shop and left,” he said. “They say they lose less money if they keep their shops closed now than if sell their goods – because it’s impossible to replace the stock at the same price.”

The stagnation has become so severe that some shops have recently advertised installment plans for clothing and shoes – an unprecedented practice in Iran and a sign of sharply declining purchasing power.

Morteza added: “The economic situation is so dire that the government no longer dares to deny it. When someone earning 400 million rials a month (around $280) – still a dream salary for many – is below the poverty line in Tehran, it means almost no worker or employee can endure the pressure anymore. Everyone has reached their limit, in every sense.”

Cautious nod from state media

Concerns over further escalation appear to be growing within official circles.

On Monday, state television – controlled by hardliners opposed to President Masoud Pezeshkian – briefly covered the bazaar protests for the first time.

Cameras were taken into shops, airing interviews in which merchants emphasized that their protests were economic in nature and driven by currency volatility rather than politics.

At the same time, videos circulating on social media showed protesters chanting anti-government slogans in several locations.

According to Morteza, while the protests so far have had a strong economic dimension, they cannot be reduced to bread-and-butter issues alone.

“Livelihood is not the only reason for people’s anger. This time, the government cannot calm society with small handouts, superficial concessions or a crackdown.”

Fear at the bottom, strain in the middle

Iran’s deteriorating economy has devastated low-income households while also eroding the lives of salaried middle-class families who once enjoyed relative stability.

Even by official figures, inflation surpassed 50 percent last month. Yet the government’s proposed budget for next year includes only a 20 percent increase in salaries for civil servants and retirees, deepening concerns over an unbridgeable gap between incomes and living costs.

Middle-class families may still live in reasonably maintained homes, but a burst pipe, a broken car, or a medical emergency can wipe out most of a month’s income, according to widespread accounts on social media.

Downsizing, once a coping strategy, now offers little relief. Iran’s housing market – particularly in Tehran – is experiencing an unprecedented slump, limiting families’ ability to sell or relocate to offset rising costs of food and utilities.

Journalist Mohammad Parsi wrote on X: “In this country… first buying a home became a dream, then a car, a phone, travel – and now even essential goods are disappearing from daily life, just like that, in one of the richest countries in the world.”

Another user, Arian Bahmani, described even buying basic snacks as a financial calculation, calling it “a frightening collapse of living standards.”

“The disaster is not that we can’t buy a house or a car – they’ve been dreams for years,” he wrote. “The disaster is that ‘500,000-rial (about 35 cents) treats are luxury purchases. When buying snacks becomes a financial risk, we are no longer citizens – we are hostages.”

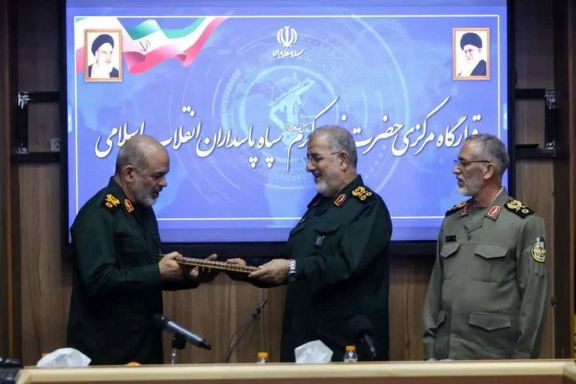

Iran’s Supreme Leader has appointed Ahmad Vahidi as deputy commander-in-chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), replacing Ali Fadavi, who was moved to head an advisory group under the IRGC commander.

The decree, issued in Vahidi’s former name Vahid Shahcheraghi and read out at a handover ceremony, said the appointment was made following a proposal by the IRGC commander. Senior Guards commanders and military officials attended the event.

Vahidi has been implicated by Argentine prosecutors in the 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish community center in Buenos Aires, which killed 85 people.

At the time, Vahidi was the head of the Quds Force, the external operations branch of Iran's sprawling paramilitary organization the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Interpol said in a 2009 statement that a red notice for Vahidi was issued in November 2007 at Argentina’s request, adding that a red notice is not an international arrest warrant and that any decision to detain an individual rests with national authorities.

Argentina’s foreign ministry said in April 2024 that it wanted Vahidi arrested in connection with the AMIA case when he traveled abroad as part of an Iranian delegation. Iran has repeatedly rejected allegations of involvement in the attack.

The United States has sanctioned Vahidi for his role in Iran’s suppression of protests, including the use of lethal force by security services during demonstrations sparked by the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini.

The Treasury Department said Vahidi oversaw law enforcement agencies involved in serious human rights abuses and had earlier been sanctioned over alleged links to Iran’s nuclear and weapons programs.

Iranian media have described Vahidi as a veteran Guards commander who held senior posts spanning the IRGC’s intelligence and overseas operations and later served in cabinet roles, including as defense minister and interior minister.