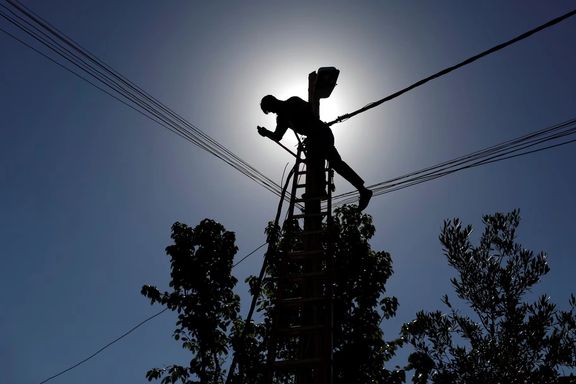

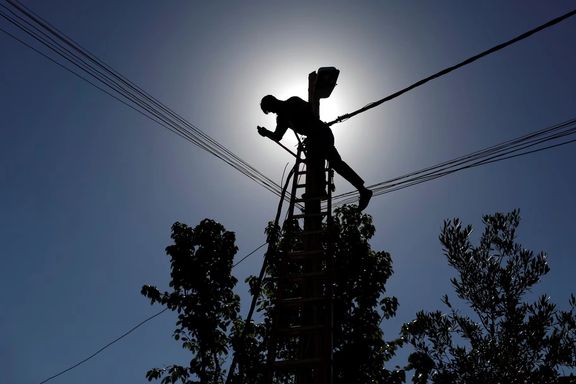

Iraq says Iranian gas supplies stop completely

Iraq’s electricity ministry said on Tuesday that Iranian gas supplies had stopped entirely, cutting between 4,000 and 4,500 megawatts from the national power grid and reducing supply hours.

Iraq’s electricity ministry said on Tuesday that Iranian gas supplies had stopped entirely, cutting between 4,000 and 4,500 megawatts from the national power grid and reducing supply hours.

“The flow of Iranian gas has stopped completely,” ministry spokesman Ahmed Mousa said, adding that some power units were shut while others were forced to cut output.

Mousa said Tehran had informed Baghdad of the halt due to “emergency conditions,” without giving further details.

He said the Iraq Electricity Ministry had switched to domestic alternative fuel in coordination with the oil ministry, and that generation remained “under control” despite the shortfall.

Iranian gas exports to Iraq had declined sharply this year after the US tightened sanctions enforcement and revoked a long-standing waiver that allowed Iraq to pay for Iranian electricity and gas imports.

Between April and August, Iranian gas exports to Iraq fell by about 40%, according to regional trade data, as Baghdad struggled to navigate sanctions while seeking alternative supplies.

Iraq’s power sector has also faced security disruptions. In November, a rocket strike forced the shutdown of the Khor Mor gas field in northern Iraq, cutting about 3,000 megawatts from regional supply.

Local Kurdish officials blamed Iran-backed armed groups for the attack, which targeted energy infrastructure critical to electricity generation.

The electricity ministry said Iraq had prepared for peak winter demand through maintenance and upgrades at power stations, and that coordination with the oil ministry would continue until Iranian gas flows resume.

Iranian pharmaceutical industry figures warned that illicit Iranian-made medicines are increasingly appearing in Afghanistan, undercutting legal exports and deepening shortages at home.

Pharmaceutical sector representatives say the flow has accelerated after Pakistan curtailed drug exports to Afghanistan, turning Iran’s subsidized market into an attractive source for traffickers.

They argue that wide price gaps between Iran and neighboring countries have made smuggling structurally profitable, sidelining legal export channels.

Drug production has increased by around 50% but shortages persist, Mohsen Abdollahzadeh, a board member of the Drug Distributors Syndicate said on Tuesday.

“Drug smuggling from Iran to Iraq and Afghanistan is so extensive that traders in those countries are unable to import medicines legally and cannot compete with smuggled Iranian drugs,” he added.

Food and Drug Administration of Iran has conceded that so-called “reverse smuggling” exists, driven by sharp price differences with neighboring markets.

However, spokesperson Mohammad Hashemi disputed a widespread surge, saying documented cases remain limited. Continued leakage, he warned, could trigger intermittent shortages and place further strain on an already fragile supply chain.

Recent talks with an Afghan delegation, Hashemi said, focused on expanding formal pharmaceutical exports and improving monitoring, a move critics say reflects belated damage control rather than a solution to entrenched enforcement gaps.

Food market shows same fault lines

The controversy mirrors developments in food markets, where currency policy shifts and the removal of subsidized exchange rates have driven sharp increases in staple prices.

Analysts say both sectors show the same pattern: multiple pricing regimes and weak oversight have encouraged arbitrage and cross-border leakage.

For consumers, the result has been recurrent shortages and rising costs, as subsidized goods – whether medicine or food – slip out of regulated channels faster than authorities can contain them.

Authorities say medicines are still available for now, but concede that delays in transferring allocated foreign exchange, mounting arrears to suppliers and dwindling inventories have pushed the sector to the brink, increasing the risk of shortages in the final months of the Iranian year, which ends on March 20.

In an economy battered by chronic inflation and currency volatility, officials say, keeping drug prices frozen shifts the burden onto manufacturers and ultimately jeopardizes national drug supply chain.

Iran’s parliament convened a closed session with senior government officials on Tuesday to assess economic conditions, as lawmakers said subsidy and currency policies had not translated into tangible relief for many households.

The session was held to share information between the government and lawmakers on how to address public grievances, Abbas Goudarzi, spokesperson for parliament’s presiding board, told reporters after the meeting.

He said a five-member joint committee had been formed between the government and parliament, with briefings delivered by the heads of the Planning and Budget Organization and the Central Bank of Iran.

Ineffective policies

Goudarzi cited oil sales, the return of export earnings and unresolved foreign-currency obligations as key factors shaping current economic conditions, saying their combined impact had produced the present situation.

He pointed to the allocation of about $10 billion in subsidized foreign currency for essential goods as an example of ineffective policy design, adding that roughly $8 billion was directed to livestock feed while consumers continued to pay market prices for basic items.

“There is no logic in allocating this volume of currency if it does not reach its target,” Goudarzi said, adding that existing mechanisms had failed to translate support into lower costs for households.

Iran introduced its preferential foreign-exchange system in April 2018 under then president Hassan Rouhani, fixing the dollar at 42,000 rials in an effort to cushion households from price shocks and ensure imports of essential goods and medicines using oil revenues.

As the gap between the official and market rates widened – and the rial slid to record lows above 1.32 million per dollar this week – the policy became increasingly costly.

The administration of Ebrahim Raisi dismantled the system as part of what it branded “economic surgery,” arguing that it fueled arbitrage, corruption among importers, and failed to benefit consumers.

Several months later, the government reinstated subsidized currency at 285,000 rials to the dollar, roughly half the market rate at the time. The scheme initially covered 25 categories of goods, though the list has since been pared back.

In recent months, preferential currency has been removed from imports of staples including rice, vegetable oil, red meat, animal feed, and some medicines.

Budget pressure builds

The Tuesday morning session, Goudarzi said, was held behind closed doors, with an open afternoon meeting scheduled with the president.

The government will submit the draft budget to Iran’s parliament on Tuesday for the first time based on the new rial, following the removal of four zeros from the national currency.

The new year's budget bill is being submitted to parliament amid signs it has been drafted as one of the most contractionary budgets in recent years.

Goudarzi described the Tuesday meeting as an attempt to coordinate the executive and legislative branches to manage economic and currency challenges.

He outlined a compressed review timetable, saying the draft budget will be examined by the combined budget committee within three days before being sent to the plenary, whether approved or rejected.

If endorsed, it will then move to specialist committees for further study under strict deadlines before returning to the combined committee and, ultimately, the full chamber.

Goudarzi noted that under parliamentary rules the government was required to submit the budget on December 23, but did so a day later because no open session was held to formally trigger the review process.

“Only in 48 hours, the Islamic Republic regime executed more than 17 prisoners,” the US State Department said in a post on its Persian-language account on Tuesday.

The State Department cited the case of Aqil Keshavarz, a 27-year-old architecture student, saying he was arrested during the 12-day war with Israel in June, denied a fair trial and executed on what it described as fabricated spying charges.

Iran’s judiciary said on Saturday that Keshavarz was executed after the Supreme Court upheld his death sentence. Rights groups have said he was tortured to force a confession, allegations Iranian authorities deny.

The State Department said more than 1,800 people had been executed in Iran so far this year.

A surge in Israeli reports and briefings on possible action against Iran could increase the risk of unintended escalation, Israeli security officials cautioned, with a Ynet analysis warning that public discussion may be misread by Tehran at a sensitive moment.

The analysis said senior security officials fear that heightened public messaging – often attributed to unnamed senior diplomatic or Western intelligence sources – could be misinterpreted by Iran at a time of fragile ceasefires and unresolved regional flashpoints, raising the risk of an unintended escalation neither side is seeking.

The recent spate of reports comes ahead of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s expected meeting with US President Donald Trump in Washington later this month, and coincides with mounting pressure on Israel’s government over stalled ceasefire arrangements in Gaza and the lack of progress toward a state inquiry into the October 7 attacks.

Israeli officials cited in the Ynet analysis said that Iran currently relies heavily on Israeli media coverage to assess Israel’s intentions, as Iranian intelligence operations inside Israel have become increasingly constrained.

Israeli authorities have disclosed that dozens of suspected Iranian espionage attempts have been foiled since the start of the war.

“If Iran concludes that Israel is once again preparing for war, it may consider striking first,” senior security officials were quoted as saying, warning that public speculation and unofficial briefings could prove more destabilizing than deliberate military signaling.

Israeli defense officials have repeatedly cautioned this year that a renewed conflict with Iran could stem from miscommunication rather than a strategic decision by either side, particularly following June’s 12-day confrontation. They stressed that recent Iranian military exercises do not necessarily signal preparations for an imminent attack.

According to Israeli assessments cited in the analysis, Iran is currently focused on rebuilding and upgrading its military capabilities, strengthening intelligence collection, and supplying weapons and funding to allied groups including Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen.

While Israeli officials believe Iran has not yet crossed thresholds that would trigger Israeli military action, they warn that Tehran could misread Israeli preparations as an imminent threat, prompting a preemptive strike that could rapidly widen the conflict.

Another major uncertainty is Hezbollah’s role in any future confrontation. During the summer conflict with Iran, the Lebanese group refrained from launching attacks, but Israeli planners are preparing for the possibility that such restraint may not hold in a future crisis.

With Gaza, the northern front and Iran all expected to feature prominently in talks between Netanyahu and Trump, Israeli officials say the government may face difficult trade-offs across multiple arenas as it seeks to preserve US diplomatic and military backing.

Israeli public broadcaster Kan News reported on Monday that Hezbollah requested approximately $2 billion in annual funding from Iran to rebuild after the war, but Tehran agreed to transfer only about $1 billion.

Kan’s Arab affairs correspondent Roey Kais said the funds arrive regularly, mainly by air and that Hezbollah members continue to receive high salaries by Lebanese standards, but rebuilding the arsenal destroyed in the conflict remains costly.

“In recent months, Hezbollah’s top leaders and the Iranian Quds Force sat down to negotiate how much money Tehran would transfer this year to Hezbollah,” Kais said.

“To this day, there are still complaints within Hezbollah’s ranks that the money arriving from the Iranians is insufficient for the organization’s needs, but despite that, it must be emphasized that everything agreed upon with the Iranians arrives precisely and regularly,” he added in a post on X.

The report comes amid scrutiny of Iran’s financial support for Hezbollah, which a US official said has totaled around $1 billion so far this year despite heavy sanctions on Tehran.

US officials targeted what they describe as Hezbollah’s “cash network,” last month, sanctioning alleged financiers who move Iranian funds through exchange houses and front companies to help the group rebuild its military infrastructure and pay fighters.

United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) policy director Jason Brodsky seized on the Kan report as further evidence that sanctions are biting, saying pressure remains a useful tool.

“The next time you hear arguments that sanctions and pressure don’t work, remember this thread. If there were no sanctions, Iran would be providing Hezbollah with more,” Brodsky posted on X.

Hezbollah has been trying to restore its capabilities after a bruising confrontation with Israel, which killed thousands of people and severely damaged the group’s command structure and arsenal.

Lebanese leaders, under international pressure, have meanwhile floated plans to disarm militias and extend state authority in the south, but Hezbollah has resisted efforts to curb its arsenal, arguing that its weapons remain essential to deter Israel.