From US-built reactors to secret enrichment sites and global standoffs, this comprehensive explainer breaks down the key moments that shaped Iran’s nuclear program and why it matters now more than ever.

Click here to read the full story.

From US-built reactors to secret enrichment sites and global standoffs, this comprehensive explainer breaks down the key moments that shaped Iran’s nuclear program and why it matters now more than ever.

Click here to read the full story.

Iran’s nuclear program has dominated global headlines for over two decades, drawing in multiple US presidents, triggering waves of sanctions, and raising persistent fears of a regional war.

Iranian officials insist the program is peaceful, but Tehran's uranium enrichment expansions have concerned Western powers and led to warnings from Israel and the United States of possible military action.

When and why did Iran start its nuclear program?

Iran's nuclear activities began in the 1950s under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as one component of a US-supported initiative to promote civilian nuclear power in allied nations. The United States helped Iran build its initial research reactor at Tehran University under the Atoms for Peace initiative. The shah envisioned a grid of reactors to power Iranian cities, coupled with enhancing the scientific stature of the country.

Iran had by the 1970s signed with France and West Germany a deal to build a number of reactors. America had in principle agreed to allow Iran to establish a full nuclear fuel cycle, including uranium enrichment and reprocessing — technology that is sensitive as it could be used to produce fuel for civilian reactors or weapons.

Western countries considered Iran a reliable ally at the time, and little global outcry was expressed over the program. That all changed with the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

What happened to the program after the Islamic Revolution?

When the shah was overthrown and Ruhollah Khomeini established the Islamic Republic, most of Iran's nuclear activities came to a halt. Foreign suppliers stepped back. Several nuclear facilities were abandoned or left unfinished. Iran's new leaders, wary of Western influence and burdened with war against Iraq, relegated nuclear development to the bottom of their agenda.

But by the late 1980s and early 1990s, Iran began to restart its program. The Islamic Republic signed agreements with Russia and Pakistan and ramped up activity at facilities like Natanz and Arak. These efforts raised suspicions, especially because Iran was operating some of its facilities clandestinely.

The IAEA was not aware of all the construction, and suspicions mounted about whether Iran's intentions were strictly civilian or not.

What contributed to the nuclear standoff?

The dissident opposition group National Council of Resistance of Iran revealed in 2002 two secret Iranian nuclear sites at Natanz and Arak. The revelation shocked Western intelligence and led to a request by the UN nuclear watchdog agency, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), for an inquiry.

Inspectors confirmed the existence of indications that Iran had conducted activity pertinent to acquiring a nuclear weapon — such as experiments on high-explosives and possible models for missile warheads.

Iran said it intended to acquire only nuclear power and not an atomic bomb. Yet its concealment of the operations from reporting contravened Iran's safeguards treaty to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that it had signed.

As a counter, the UN Security Council imposed a set of resolutions that insisted Iran stop suspending its reprocessing and enrichment. Sanctions were enforced upon Iran's defense, energy, and banking. The confrontation hardened over the decade that followed.

What was the purpose of the 2015 nuclear accord?

After years of negotiations, Iran and six of the world's top powers — US, UK, France, Germany, Russia, and China — agreed on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2015.

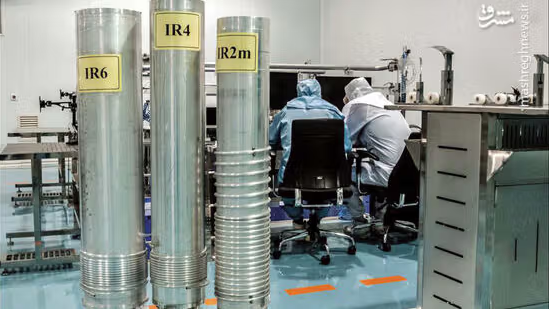

Under the deal, Iran agreed to restrict uranium enrichment to 3.67% purity — well short of weapons-grade. The deal also limited Iran's partially enriched uranium stockpile to 300 kilograms. It dismantled and stored thousands of centrifuges. It agreed to intrusive IAEA inspections such as supply chain tracking and declared facilities.

In return, Iran gained relief from international sanctions, including the unfreezing of billions in foreign assets and re-entry into international oil markets.

The US administration's allies greeted the deal as a major non-proliferation achievement. President Barack Obama called it "a long-term deal that will prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon."

The United States why pulled out of the deal?

The United States withdrew from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, when then-President Donald Trump announced that the agreement had failed to prevent Iran from expanding its ballistic missile program or aiding armed groups across the region.

Announcing the deal "a disaster," Trump reimposed sweeping sanctions in what his administration described as a "maximum pressure" campaign to push Iran to accept more restrictive terms.

“Iran’s leaders will naturally say that they refuse to negotiate a new deal. That’s fine. I’d probably say the same thing if I were in their position. But the fact is, they’re going to want to make a new and lasting deal,” Trump said at the White House at the time of the withdrawal announcement.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) confirmed in a series of quarterly reports that Iran remained in compliance throughout the remainder of Trump's term — including May, August, and November 2018 inspections, as well as early 2019.

Tehran's gradual erosion of the accord came only after Joe Biden's election. On January 4, 2021, just over two weeks before Biden took office, Iran resumed 20% enrichment at its Fordow plant. In February, it prevented IAEA inspectors from visiting its facilities and began producing uranium enriched to 60% by mid-April — far beyond the limit of the accord's 3.67%, but short of the 90% necessary for weapons-grade material.

Iran currently has a reserve of enriched uranium above the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) threshold, enriched to 60% purity, according to the IAEA.

Although Biden officials have spoken of Trump's withdrawal as the trigger for the deal's collapse, timelines show that Iran did not commit serious violations until the end of Trump's presidency.

How close is Iran to developing a nuclear weapon?

According to US intelligence estimates Tehran is now able to produce enough highly enriched uranium for a single nuclear weapon within weeks if it were to decide to do so.

In a recent TV interview, Ali Larijani, the Supreme Leader's chief adviser warned that Iran will be able to make weapons if pushed into a corner. “If you make a mistake regarding Iran’s nuclear issue, you will force Iran to take that path, because it must defend itself,” he said.

The IAEA has expressed concern about traces of uranium that remain unidentified at undeclared locations and reports that Iran has not provided sufficient explanations on a number of issues that remain outstanding.

What is the official position of Iran?

Iran continues to say that its nuclear program is peaceful. "The official stance of Iran in rejecting weapons of mass destruction and regarding the peaceful nature of the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program is clear," foreign ministry spokesman Esmail Baghaei said.

But officials generally follow such statements with warnings regarding self-defense. Baghaei cited a recent speech of the Supreme Leader to the effect that Iran would arm itself "to the extent necessary for the defense of Iran."

Iranian leaders present the US and Israel as the aggressors. "The enmity from the US and Israel has always been there. They threaten to attack us, which we don’t think is very probable, but if they commit any mischief, they will surely receive a strong reciprocal blow," Khamenei said in March 2025.

Why are the US and Iran negotiating now?

US and Iranian officials conduct talks in Oman hoping to revive the nuclear talks. The discussions, President Trump announced, will be direct, while Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi announced that communication would be through intermediaries.

The diplomatic push coincides with rising tensions. Trump has sent a letter to Khamenei threatening to punitive military strikes if there is no deal. “I’ve written them a letter saying, ‘I hope you’re going to negotiate because if we have to go in militarily, it’s going to be a terrible thing,’” Trump said.

What is Israel's role in the nuclear standoff?

Israel has always opposed the JCPOA and sees a nuclear Iran as an existential threat. Israel is believed to have orchestrated sabotage plots against Iranian nuclear facilities and assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists in the last two decades, based on intelligence officials quoted by several Western news outlets.

Although Israel has not publicly taken responsibility of all the incidents, it has committed to acting if diplomacy fails. Iran has, in turn, correlated its nuclear stance with the danger of Israel's undeclared nuclear capacity and record of strikes.

What's on the line now?

With Iran's uranium enrichment to new record levels and diplomacy at an impasse, the threat of escalation hangs perilously close. The deployment of US B-2 bombers to the region, as well as Tehran's threat to employ its underground cities of missiles as a counter-attack, is what accentuates the mounting tension. The crisis has been amplified by further incendiary language against Iran from Donald Trump.

Both sides still express a preference for negotiation, but there is profound mutual distrust. America wants tighter terms; Iran demands sanctions relief and guarantees the deal won't collapse like before.

The success of current efforts has the potential to decide not just Iran's nuclear future but the broader dynamics of Middle Eastern security for decades to come.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei's oft stated mantra of "no war and no negotiations" with the United States became untenable when US President Donald Trump gave a stark ultimatum that he reach a nuclear deal or face attack.

Read the full analysis here.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei's oft stated mantra of "no war and no negotiations" with the United States became untenable when US President Donald Trump gave a stark ultimatum that he reach a nuclear deal or face attack.

But his acquiescence to US-Iran talks in Oman on Saturday is no wholesale foreign policy rethink or road to Damascus moment: it’s a calculated attempt to buy time.

With Trump back in office and US military power amassing in the region, Khamenei is reverting to a familiar strategy: de-escalate just enough to avoid war, preserve the Islamic Republic’s strategic position, and wait out American pressure.

The meeting on Saturday in Muscat is not aimed at resolving the nuclear standoff or reimagining Iran’s regional role. It’s about lowering the temperature while holding onto the core pillars of Iranian power: the nuclear program, the missile arsenal and the regional proxy network.

This is a playbook Khamenei has used for decades: resist until pressure becomes untenable then pause, rebrand retreat as “heroic flexibility,” and regroup.

The phrase was deployed in 2013 to justify his negotiations with the Obama administration, casting diplomacy with Tehran's hated enemy as in line with precedent set by beleaguered Islamic leaders in times past.

Hibernation

In 2019, when Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe brought a message from then-President Trump, Khamenei publicly trashed him: “I do not consider Trump a person worthy of exchanging messages with.”

At the time, there was no imminent threat of war. Today is different. US B-2 stealth bombers are within striking distance and two carrier strike groups patrol the region.

When a message reportedly containing a direct threat was delivered recently via an Emirati official, Khamenei studied it and the circumstances closely.

His assent to talks is less a pursuit of detente and more a strategic hibernation.

Khamenei knows war is the one scenario that could shatter the domestic control and regional clout the wily 85-year-old autocrat has built up for decades.

Slowing enrichment, muzzling proxies and entering talks buys him time without sacrificing his accomplishments.

The Islamic Republic is weakest on its home front. Sanctions have ravaged the economy. Sporadic protests from 2017 to 2022 - all quashed with deadly force - have exposed cracks in the edifice of his rule.

A war could push those toward breaking point.

A tactical negotiation, by contrast, offers the topmost leadership breathing space on the streets, among elites and within the ruling system.

Survival instinct

A keen survival instinct has defined Khamenei’s rule. Since becoming President in 1981 and then Supreme Leader in 1989, he has outlasted seven US presidents and weathered assassination attempts, sanctions, cyberattacks, sabotage, isolation and bombing.

Key to his longevity is adjusting tactics, but never core goals.

The 2015 nuclear deal was not a concession but a gain. Iran accepted temporary caps on enrichment but secured international recognition of its right to enrich—a red line Khamenei had long defended.

The 3.67% cap was low, but the principle was enshrined. A higher percentage could wait. When Trump left the deal in 2018, Khamenei didn’t escalate immediately, but bided his time.

Once Biden, perceived as less belligerent, came to office, Iran accelerated its program. Enrichment rose to 60% by the end of his term, advanced centrifuges were installed, and underground facilities expanded.

According to the United Nations nuclear watchdog, Iran now possesses enough highly enriched uranium to build several nuclear weapons if it chooses to.

De-escalate, regenerate

With Trump back in power and military pressure mounting, Khamenei is adapting to survive. The hope is likely to de-escalate, rein in the nuclear program, quiet the proxies, and preserve its infrastructure to avoid provoking direct confrontation.

Iran’s influence in the region has eroded significantly. Hezbollah is under pressure. Hamas is boxed in. Perhaps most significantly, Iran has lost Syria as a key ally, depriving it of a key pillar of its regional axis.

Still, Iran does not see these setbacks as irreversible. Israeli officials often describe the Islamic Republic as an octopus with a head in Tehran and limbs spread across the region. When an octopus loses a limb, they can grow back.

Khamenei believes that if the system survives Trump, its regional reach can regenerate.

Time and money

Key to those hopes will be mollifying the United States for as long as Trump is in office - a goal which could plausibly be achieved by restraining nuclear activity and scaling back proxy operations, with or without a deal.

If that restraint can be packaged into an agreement, all the better.

A deal would formalize what he is already prepared to do and buy yet more time. If it comes with sanctions relief or cash, it will be no compromise but an outright win: a payment to wait Trump out.

But the red lines remain. If Trump’s team demands the dismantling of Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, permanent limits on missile capabilities or the disbanding of its regional allies, talks will collapse.

Khamenei seeks not peace in our time but more time on the clock.

Diplomacy, in this context, is not a gateway to a new regional order but a heat shield against a blowup. The goal is not to settle but to survive.

A calculated pause could mark the start of another cycle of hibernation in a long game in which confrontation is still the overall policy of a supreme leader who knows war is the only thing he cannot afford.

An adviser to Iran’s foreign minister said on Saturday that the Islamic Republic has already achieved a political win by entering into indirect negotiations with the United States in Oman, regardless of whether the talks succeed or fail.

“Whether the talks fail or continue, the Islamic Republic has already won,” Mohammad Hossein Ranjbaran, adviser to Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi, wrote on X.

Ranjbaran said Iran had both preserved its national dignity and demonstrated goodwill to the world through indirect engagement. “With indirect negotiations, it both preserves national pride and shows goodwill to the world — even when many countries cannot establish a rational connection with the current US president,” he added.

Iraqi Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein has welcomed the Iran–US talks in Oman, expressing hope that the negotiations will contribute to regional stability, the Iraqi News Agency (INA) reported Saturday.

The comments came during a meeting with Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Saeed Khatibzadeh on Friday in Antalya, Turkey, on the sidelines of the Antalya Diplomatic Forum.

According to a statement from Iraq’s Foreign Ministry, “Fuad Hussein welcomed the talks scheduled to be held Saturday in the Sultanate of Oman between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the United States of America, expressing his hope that these negotiations will yield positive results that contribute to achieving stability in the region.”