According to two members of Pezeshkian's delegation, the 86-year-old hardline theocrat had privately told the relatively moderate president he could start a secret dialogue if it headed off the return of United Nations sanctions due for the week's end.

But as their plane crossed the Atlantic, Khamenei delivered a fiery speech on state television categorically ruling out any talks with Washington in a reversal that stunned Pezeshkian and Iran's top envoy, according to the two sources.

Iran’s foreign minister Abbas Araghchi later confided before a closed-door meeting of Iranian experts and academics that renewed US talks were the only avenue to halt the return of the European-triggered sanctions, three participants told Iran International.

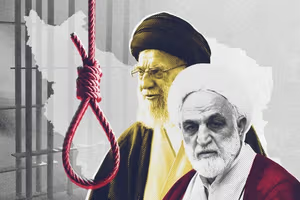

The episode shows the Supreme Leader and his top civilian officials are deeply at odds about how to chart Tehran's way out of the lingering impasse over its nuclear program which threatens further conflict after a punishing Israeli-US war in June.

Araghchi and US President Donald Trump's special envoy Steve Witkoff had held indirect talks for two months before a surprise Israeli military campaign on Iran on June 13.

The attacks were capped off by US strikes on three key Iranian nuclear sites which appeared to bury much of Iran's highly-enriched uranium stockpiles but left the ultimate resolution of the West's standoff with Iran on its nuclear ambitions unresolved.

Khamenei in his speech and Pezeshkian in an address before the United Nations again said Tehran does not seek a bomb and hit out at sanctions as unfair and illegal.

Closed-door meeting in Manhattan

On Friday, Sept. 26, shortly after the UN Security Council rejected Russian and Chinese proposals to suspend the snapback of UN sanctions on Iran, Pezeshkian and Araghchi met with a small group of invited Iranian experts and academics at The Luxury Collection Hotel in Manhattan.

The session was scheduled to last an hour, but before it began, Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi lingered in the lobby with a few of the invitees, speaking more candidly than usual about Tehran's predicament.

“The only way to stop the snapback was direct talks,” Araghchi told them. “And only direct talks can prevent further escalation. But we are not allowed to engage.”

He even suggested the participants urge Pezeshkian to try to persuade the Supreme Leader, but none of them did that.

Khamenei's U-turn on secret US talks

Three participants in the private meeting later recounted to Iran International, on condition of anonymity, that Araghchi elaborated further before the session began.

He explained that before leaving Tehran, Pezeshkian had raised the idea of direct engagement with the Supreme Leader. The Americans, he said, had laid out three firm conditions for such talks with envoy Steve Witkoff:

1. Public, on-the-record meetings with the press present before and after.

2. Disclosure of the location of 400 kilograms of highly enriched uranium.

3. Full access for inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Araghchi said Ayatollah Khamenei had rejected public negotiations but explicitly agreed that secret direct talks would be acceptable if they could stop the snapback.

Yet by the time the delegation landed in New York, the Supreme Leader had gone on state television to rule out any talks at all — directly contradicting his private position and leaving the delegation blindsided.

Inside Tehran’s New York huddle

The private hourlong session with Pezeshkian brought together a group of academics and experts including Houshang Amirahmadi, an academic and longtime advocate of US–Iran engagement; Vali Nasr, a scholar and former State Department adviser; and Trita Parsi, the executive vice president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

The other participants included Hadi Kahalzadeh, a fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft; Djavad Salehi Esfahani, a professor of economics at Virginia Tech; Masoud Delbari, a senior energy expert and analyst; Ali-Akbar Mousavi Khoeini, a former Iranian parliamentarian and reformist activist; Mohammad Manzarpour, a freelance journalist; and Yousef Azizi, a PhD candidate at Virginia Tech.

Amirahmadi spoke first, and for nearly half the meeting. For about 25 minutes he laid out a stark binary: surrender or go nuclear. He argued that the United States’ main problem with Iran was not its nuclear program but its strength in the region. Washington, he said, does not want a “powerful Iran.” He strongly advised Pezeshkian that Iran must invest more heavily in its missile and military capabilities, declaring that the time had come to pursue a nuclear deterrent. His remarks went on so long that Iran’s UN envoy, Amir Saeed Iravani, eventually asked him to conclude.

Pezeshkian, throughout, took careful notes. When he returned to Tehran, he told journalists at the airport that in his meeting with Iranians, “one of the respected figures” had said the United States’ real problem with Iran was its strength. He did not name Amirahmadi but directly echoed his point.

Because of the length of Amirahmadi’s remarks, only a few others had time to weigh in. Parsi said the major sanctions were American sanctions, with UN measures adding complications but not being the primary concern. He added that despite the UN sanctions, he expected China to continue buying Iranian oil, saying Beijing would likely ignore the restrictions. Both Araghchi and Pezeshkian nodded in agreement. Parsi also insisted that direct dialogue with Washington remained the only way to avoid escalation and prevent Israel from exploiting Iran’s isolation.

Nasr offered a bleaker assessment, saying Tehran had missed its chance under President Biden and that little could now be recovered. He spoke briefly and did not engage further.

A system in crisis

The contradictions at the heart of Tehran’s decision-making were unmistakable. Privately, Khamenei had given conditional approval for secret talks, and Araghchi confided this to a few attendees, making clear that Iran’s leadership understood direct dialogue was the only path left.

Publicly, however, the Supreme Leader reversed himself overnight, denouncing all negotiations and leaving his own president and foreign minister uncertain of their mandate.

The episode revealed a system in crisis: with the president, the foreign minister, and many political figures pressing for de-escalation as the only way to avoid another war, while Khamenei alone stood in the way, shifting positions in a manner that even his closest envoys struggled to navigate.

The president’s trip to New York, meant to showcase pragmatism, instead underscored paralysis.

Editor’s Note:

Our initial report, based on sources, said that Farnaz Fassihi attended the meeting. The New York Times has since issued a statement saying that she was not present. Accordingly, her name has been removed from the report.