Then, as now, Iran faced a grinding impasse: Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini resisted UN Resolution 598 which called for an end to hostilities until the cost of defiance became unbearable.

The resolution, passed on July 20, 1987, demanded a ceasefire, prisoner exchanges and a return to recognized borders.

Saddam Hussein accepted immediately. Khomeini refused, vowing that “the war should continue until the end of all seditions in the world.”

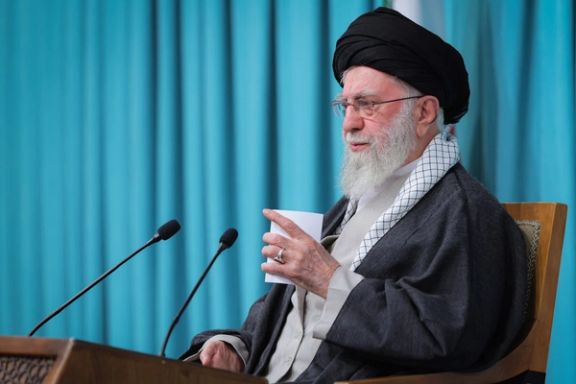

Washington warned of sanctions, and then-President Ali Khamenei told the UN General Assembly Iran was “determined to punish the aggressor.”

‘Poison chalice’

The war dragged on another year, draining finances and costing thousands more lives.

By August 1988, even then-Revolutionary Guards commander Mohsen Rezai conceded it was unsustainable. Morale had collapsed, tens of thousands were dead and Iran’s military capabilities shattered.

Khomeini finally relented, confessing that accepting Resolution 598 was “more deadly than drinking from a poisoned chalice.”

The phrase became a metaphor for concessions made too late, when pride collides with reality.

That poisoned chalice haunts Iran again.

No turning back

After the 12-day war with Israel, many in Tehran urged the leadership to abandon uranium enrichment and open direct talks with Washington, arguing only such a step can relieve Iran’s economic misery.

Yet Khamenei remains unmoved, caught between hardliners demanding defiance and moderates pleading for pragmatism.

Fond of channeling his predecessor, Khamenei had likened agreeing to a 2015 nuclear deal as drinking from that same poison chalice.

The IAEA continues to demand answers on uranium reserves. The Trump administration insists Iran’s nuclear program has been dismantled and warns against escalation.

Israel, emboldened by its strikes on Tehran and regional proxies, demands not only an end to Iran’s missile program but at times even regime change. Europe has its own conditions for halting or delaying the snapback of sanctions.

'Slap in the face'

On Tuesday, on the eve of President Masoud Pezeshkian’s address to the UN General Assembly, Khamenei poured cold water on any hope of reconciliation, effectively torpedoing the president’s diplomatic message before it was delivered.

Doubling down on a red line, he declared: “Negotiating with the United States under the current conditions carries harms for Iran, some of which are irreparable ... This is not negotiation, this is dictation.”

Hours earlier, Trump had mocked him at the UN as Iran’s “so-called” Supreme Leader. Khamenei shot back that Iranians would “give a slap in the face to the person" making arrogant demands of Iran.

Inside Iran, moderates call for dialogue, while hardliners close to Khamenei, including the editor of the state-funded Kayhan newspaper, deride them as “kissing Trump's bottom.”

The result is paralysis.

For Khamenei, the options appear stark: war or negotiation. A years-old quote of his "neither war nor negotiation" was not long ago plastered as a mural on a Tehran high-rise. But history suggests delay carries its own cost.

In 1988, the poisoned chalice was forced upon Khomeini only after Iran’s military was exhausted, its economy shattered, and its people demoralized.

Today, the risk is that Khamenei repeats the same mistake—clinging to defiance until the only choice left is abject humiliation.