In an op-ed published this week in one of Iran’s leading economic newspapers, Donya-ye Eghtesad, the economist Massoud Nili described the country’s current predicament as a failure of governance that left mounting problems and public grievances unaddressed.

“The current situation marks one of the saddest and most critical junctures in Iran’s history,” Nili wrote, “a moment in which thousands of Iranians — mainly young people — lost their lives in less than 48 hours.”

He argued that “a combination of poverty, unemployment, inequality, inflation, psychological insecurity under the looming shadow of war, and cultural conflict placed young Iranians at the center of the crisis.”

The unrest began in Tehran’s historic Grand Bazaar in late 2025, initially driven by slogans reflecting economic hardship. Over the following week, they broadened into nationwide demonstrations calling for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic.

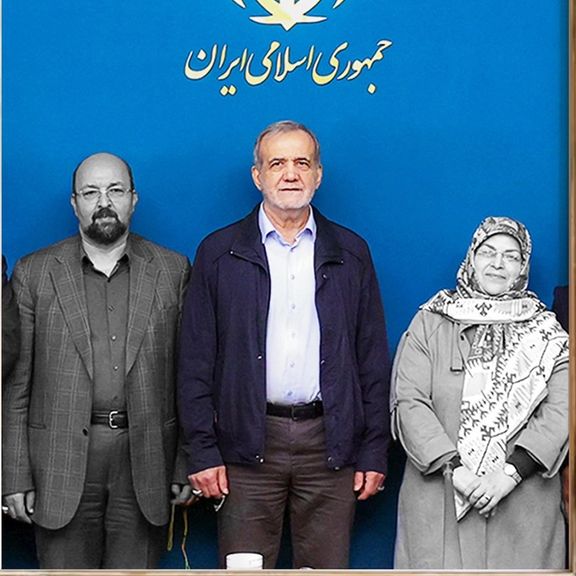

Protests peaked on January 8 and 9, following a call for coordinated actions by exiled prince Reza Pahlavi.

As many as 36,500 people were killed during the crackdown on those two days, according to an internal assessment leaked to and reviewed by Iran International.

Among the clearest warning signs, Nili noted, was the existence of nearly 12 million young Iranians who are neither employed nor enrolled in education.

Iran’s labor market, he wrote, has been effectively stagnant since 2009. While the working-age population increased by 4.4 million, the economy created only about 200,000 jobs, even as roughly 700,000 people lost employment.

Official figures suggest that net job creation has approached zero in recent years.

Other economists have echoed Nili’s assessment in the weeks since the protests and their violent suppression.

Speaking at Tejarat Farda’s economic forum in late January, Mohammad Mehdi Behkish described the protests as the product of “forty years of flawed governance and policymaking,” arguing that rigid political and economic structures had pushed society toward a breaking point.

Another prominent economist, Mousa Ghaninejad, pointed to the scale of the deterioration. In 2011, he said, fewer than 20 percent of Iranians lived below the poverty line. Today, that figure has risen to roughly 40 percent.

Declining oil revenues have further constrained the state’s ability to provide social support, while access to adequate nutrition and medical care has sharply declined.

Official data show inflation has exceeded 40 percent for at least two years, eroding purchasing power even among government employees and military personnel.

High inflation has enriched groups with preferential access to state-linked resources, widening inequality and deepening social resentment.

Nili concluded that a convergence of poverty, unemployment, inequality, psychological insecurity under the shadow of war, and cultural conflict had placed young Iranians at the center of the crisis.

Writing from inside Iran, Nili confined his analysis to economic and social indicators and avoided the political roots of the crisis—the deepening rupture between the state and a society that has come to resent the worldview and governing vision of its rulers.

He did mention “realities”, however, that if ignored, would steer the country toward “an extremely dangerous future.”