The widening gap between the two suggests not tactical ambiguity but strategic confusion—and it is most visible in the conduct of Iran’s foreign minister and chief negotiator, Abbas Araghchi.

Days after returning from Muscat, where he exchanged messages with US envoys in indirect talks, Araghchi embarked on an extended media tour at home, laying out rigid red lines that either were not conveyed to the Americans or were deliberately softened in private.

At home, Araghchi insists that Iran “will not stop enrichment,” that its stockpile of enriched uranium “will not be transferred to any other country,” and that it “will not negotiate about its missiles, now or in the future.”

Abroad, he has described the Muscat talks as “a good beginning” on a long path toward confidence-building.

The two messages are difficult to reconcile. Together, they suggest an intention to stretch out negotiations—an approach the United States under President Donald Trump has shown little interest in accommodating.

Even if these positions were not stated directly to US interlocutors, they have now been aired publicly. The question is no longer what Iran’s red lines are, but which audience Tehran believes matters more.

Other senior officials have reinforced the same internal message. Iran’s nuclear chief, Mohammad Eslami, said Tehran would be prepared to dilute its 60-percent enriched uranium only if all sanctions were lifted first—a familiar posture of maximum demands paired with minimal, reversible concessions.

This hardening rhetoric contrasts sharply with Iran’s underlying position.

Tehran enters these talks economically strained, diplomatically isolated, and politically shaken by the bloody crackdown on protests in January. Sweeping arrests of prominent moderates over the weekend have further narrowed the state’s already diminished base.

Still, for domestic audiences, defiance remains the preferred language. Hossein Shariatmadari, the hardline editor of Kayhan, warned after the Muscat talks that “the United States is not trustworthy” and urged officials to “keep our fingers on the trigger.”

State-affiliated outlets have amplified that tone, declaring the Oman talks a “political victory for Iran” without explaining what was won. State television has gone further, airing AI-generated footage portraying Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei as having “defeated” the United States.

More extreme claims have circulated as well. Ultraconservative lawmaker Mahmoud Nabavian asserted on state television that Trump had “begged” Iranian commanders to allow a limited strike—echoing earlier efforts to recast confrontations with the US as evidence of dominance.

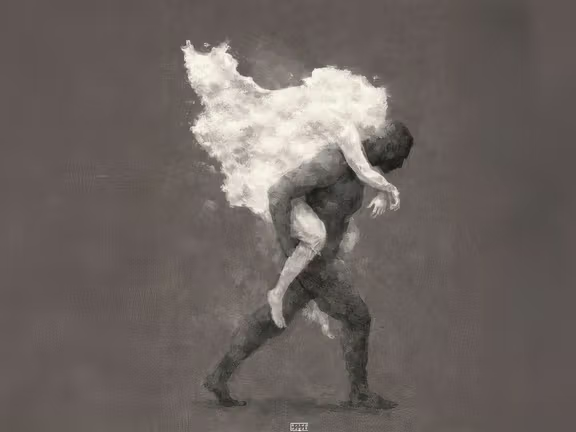

Taken together, these messages point to a leadership struggling to reconcile its external need for sanctions relief with its internal reliance on confrontation. Diplomacy abroad requires flexibility; legitimacy at home, the system appears to believe, still demands bravado.

It is the Supreme Leader who must ultimately arbitrate between these competing narratives. Ali Khamenei has long proven adept at sustaining both at once—and at bearing responsibility for neither. Whether he can repeat that balancing act one more time remains an open question.