Tehran City Council Plans To Assign 'Mega Projects' To The Guards

The chairman of Tehran’s city council has said that the municipality “has a strong desire” to give the city’s "development projects” to the Revolutionary Guard.

The chairman of Tehran’s city council has said that the municipality “has a strong desire” to give the city’s "development projects” to the Revolutionary Guard.

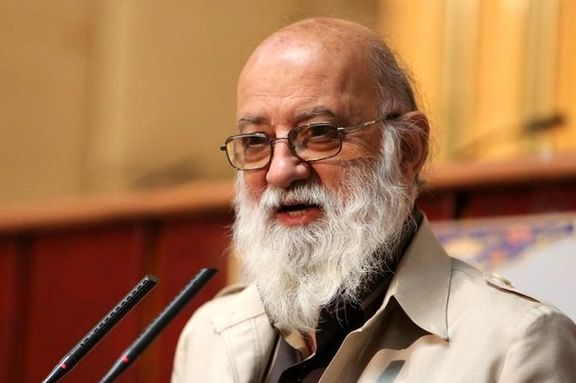

Mehdi Chamran told Tasnim news agency, affiliated with the Islamic Revolution Guard Corps (IRGC), that mega projects can go to the Guard’s Khatam ol-Anbia construction conglomerate. He did not reveal any details about the extent of the projects.

Hardliners won the absolute majority in Tehran’s city council in June elections, as reformists controlling the municipality were pushed out of the political scene in the past four years both by hardliners controlling elections and people losing hope in the reform movement.

Tehran’s municipality was mired in corruption during the 12-year mayorship of current parliament speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and owes billions of dollars to creditors.

Three of Ghalibaf’s aides have been convicted of corruption and sentenced to prison terms, but Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has continued to support him. Ghalibaf and most of his aides were members of the IRGC.

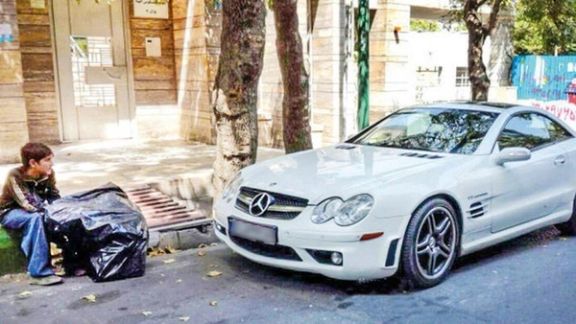

Expanding shantytowns and slums around Iran's large cities have become a serious security problem for the Islamic Republic as unrest has grown in recent years.

According to experts, living in shantytowns has now become a normal part of life for a growing number of Iranians.

Mohammad Reza Mahboobfar, a member of the Iranian Land Management Association, stated on May 28, 2020, that more than 38 million people now live in shantytowns across Iran and 7.6 million people live in the vicinity of cemeteries.

By definition, a shantytown or slum refers to a poor neighborhood formed around a large city with residents who cannot afford to live in the city proper because of poverty.

Currently, there are almost no major Iranian cities without a significant portion of the population living on the outskirts in very poor and deplorable conditions. There are two main reasons for this phenomenon, which became accentuated after the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979.

First, migration of villagers who leave their villages due to poor living conditions and move to cities in hope of a better life. But because they cannot afford the high cost of living in cities, they end up living in sheds around cities.

Second, the catastrophic economic situation in Iran, with inflation above 50% has caused prices to skyrocket. Given that wages and salaries have not increased in line with the inflation rate, it has forced some in the lower middle-class, which is a large portion of urban residents, to leave their houses and apartments in the cities and move to much cheaper housing in what are considered shantytowns.

This quick expansion has been at such an extent that some regime officials refer to it as a security problem for the regime.

Some have said that as much as 80% of Iran's population currently lives below the poverty line, and one-third of Iran's labor force is unemployed. Many factories and manufacturing plants have either been forced to shut down or operate at less than half capacity.

Many youths, despite having university degrees, are working as laborers, or as cab drivers. All these factors have caused a significant portion of these people to no longer be able to afford the high cost of living in the cities, and as a result, they have moved to the outskirts of cities, where the cost of living is lower.

Although there are no accurate and up to date statistics of the actual number of these slum dwellers, according to figures from two years ago, more than 2.5 million people live on the outskirts of Tehran, 1.3 million people around the city of Mashhad, more than 800,000 people on the outskirts of Tabriz, about half million people live around Esfahan, 400,000 people around the city of Ahvaz, 300,000 people around the city of Kermanshah, and this goes on for all the major cities. This situation is getting worse by the day as poverty increases.

The scale of this problem has reached a point where it has become one of the most serious issues for the Iranian regime.

Living on the outskirts of cities is tough for the residents. They have little access to sanitation such as clean running water, sewage system, electricity. They have no cultural and educational facilities such as standard schools, park, sport fields, proper hospitals, and most importantly security.

Most of the people living in these areas are either unemployed or have unstable daily jobs. For this reason, they are forced to resort to illegal activities such as drug trafficking, theft, prostitution, and other crimes for their survival, and many of them are drug addicts.

According to Tehran Prosecutor Al-Ghassi Mehr, 90% of those who are sent to prison for drugs or robbery are unemployed. These people, most of whom are young not only have no hope for a better future but also have nothing to lose. These days, it has become common to see scenes of armed robberies or theft of cars captured on CCTV cameras.

But petty crime does not worry the regime. What worries Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and regime officials is the possibility of another uprising like the one in November 2019 when thousands of people in various locations suddenly came out into the streets to protest a hike in fuel prices. Youth from slums took control of many neighborhoods.

In more than 100 cities some of them set fire and destroyed government symbols, such as 900 bank branches, 3,000 bank ATMs, 80 department stores owned by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), and many police vehicles, police stations, militia (Basij) centers, seminaries, and statues and posters of Khamenei and Khomeini. But remarkably in this uprising, no shops, and property belonging to ordinary people were looted or damaged.

According to officials, Khamenei, seeing that the uprising was about to lead to the overthrow of his regime, ordered his forces to open direct fire on the people. Khamenei by deploying IRGC, armored vehicles, and even attack helicopters, killed more than 1,500 people in the streets within 2-4 days and imprisoned 12,000 people suppressing the uprising.

Of course, Iran had witnessed another major uprising in 2009, which took place after the controversial reelection of populist president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But there was a major difference between that uprising and that of 2019 nationwide protests. In 2009, most of those who took to the streets were the middle-class city residents, but in 2019 almost all those who took part in the uprising were from lower strata of society, especially the residents of slums,who used to support the regime. This time, they were demanding basic living standards. Through decades of suffering and hardship, the protestors had come to the unshuttering conclusion that the top leadership of the Islamic Republic was mired in corruption and would do nothing to improve their welfare and living conditions.

Opposition to the government among the lower classes, who now make up most of the society, has become a major threat to Khamenei and his president, Ebrahim Raisi. They are very much aware that another widespread uprising, like November 2019, could not easily be controlled. Fear of such a danger led Raisi to promise in his election campaign to build one million housing units a year for low-income groups.

The Raisi government is nursing a 50 percent budget deficit, or 22 billion dollars in free market exchange rate, and is incapable of budgeting for even 10,000 housing units a year.

Some in the Iranian regime's media say that shantytowns in Iran are like a barrel of gunpowder that is about to explode.

Mohammad Reza Mortazavi, Secretary-General of the House of Industry and Mines, said in an interview with Etemad online on May 25, 2020: "It is very clear to me that one day people will pour into the streets and take over the Bastille Hills ... Poverty is the result of an unjust distribution of wealth.”

Iran’s hardliners keep silence about the nuclear talks because they are engaged in discussions among themselves, a top political expert in Iran has said.

Rahman Ghahremanpour, an analyst of Middle East politics told ISNA news website on Saturday that the ruling hardliners are deliberating what to do about the talks and if they have to make concessions, how to present it to the public.

President Ebrahim Raisi (Raeesi) during his campaign avoided negative statements on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, because his team knew that public opinion was in favor of a deal that would lift the sanctions, the expert argued. They also believed that a deal was imminent, and they stopped the Vienna talks in June until they would form a government and with consensus already existing among hardliners, they would finalize a deal with the West.

Ghahremanpour also argued that foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian’s tough positions during his trip to New York in September was meant for the local political environment to show toughness to Iranian hardliners. That did not mean a change of position by Raisi and his government to turn their backs to talks.

This expert’s views could be one aspect of the dynamics taking place in Iran, but he did not mention Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s commanding role in the nuclear issue, and the fact that if the Leader decided to return to the talks, most certainly hardliners would fall behind the decision. It could also be the case that Khamenei is the one who cannot decide how to make concessions after bashing the West for years as untrustworthy and deceptive.

Ghahremanpour insisted that “the regime’s policy is still to reach an agreement, but it should be a defensible agreement,” in terms of public opinion. Hardliners should be able to defend any agreement they make.

Given the fact that public opinion in Iran is in favor of a deal, it is not clear why the hardliners are hesitating. Ghahremanpour does not explain this, but he could be referring to the public questioning concessions in the sense that if the regime had to retreat on many issues why it did not reach an agreement earlier and avoid the economic pain that has impoverished more than half of the population.

Ghahremanpour mentions a possible quandary hardliners faced. He says that for eight years they attacked every move former president Hassan Rouhani made. Now, Raisi needs an agreement because the economic situation is untenable but how the hardliners can explain concessions they were criticizing during Rouhani’s two terms.

Ghahremanpour also confirms a suspicion many observers had in the spring during the presidential campaign that hardliners were preventing an agreement in Vienna because they did not want Rouhani to take the credit.

“An agreement that is in the interest of the regime is not necessarily defensible for hardliners,” he said, adding that it is now very clear that if Raisi’s team had allowed Rouhani to reach an agreement before the June elections, it would have made life easier for the new government.

He went on to say that finalizing and executing an agreement is much harder than hardliners could imagine. “The JCPOA seems to be like picking a fruit that has ripened on the tree. All you need to do is reach out and grab it,” Gharemanpour said, but that is exactly what eluded former foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif.

Now, hardliners are stuck between the outcomes that former presidents Ahmadinejad and Rouhani experienced in the nuclear issue, he said, but Raisi has to make up his mind. “They cannot delay an agreement for long. They either have to abandon the idea of an agreement, which would be a costly decision, or they should come up with a roadmap for negotiation,” Ghahremanpour said.

Iran’s health ministry said Tuesday that use of the China’s Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccine would continue for pregnant women and ruled out the United States-made Pfizer.

A ministry statement said the issue had been discussed at the cross-government National Vaccination Committee. Health minister Bahram Eynollahi had said on September 23 that some US-made vaccines would be imported for vaccinating expectant mothers but would not be generally available.

Data over vaccines in pregnancy has been limited. While a major study earlier in the year deemed the US-made Pfizer and Moderna safe for expectant mothers, the World Health Organization has also recommended they receive Sinopharm.

A few days ago, Fars news agency, which is affiliated to the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), launched an online campaign against importing Pfizer vaccines. On Tuesday Fars quoted Professor Ali Karami, a controversial biotechnology professor at the IRGC Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, saying the Pfizer vaccine contained a "group of genes" that could affect the recipient’s DNA. "Professor Karami's statement is a warning to take immediate action and not to put pregnant mothers and the future generation at risk," Fars noted.

Karami who has advocated other conspiracy theories in the past and ardently opposes the use of US-made vaccines claims that the US has created a vaccine to reduce religious fundamentalism with which the Pentagon could vaccinate large populations in the Middle East. "The virus in this vaccine purportedly has been tested and shown to reduce fundamentalism and religiosity in all who are infected by damaging what is called the GOD gene," Karami said at a conference in 2016.

Iran has now fully vaccinated 17 percent of the population, according to figures from John Hopkins University. Daily Covid deaths peaked at around 700 in August during a fifth wave of the pandemic but in recent weeks have fallen to under 300.

According to the latest figures released by the health ministry, 37.7 million of 84 million Iranians have received one dose and 16 million both doses of the Covid vaccine, a total of 53.8 million.

Many hardliner political, military and media figures in Iran welcomed Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s January 8 order to ban importing the US-made Pfizer and Moderna, and British-made AstraZeneca, vaccines based on conspiracy theories that the West can contaminate the vaccines to harm Iranians.

While many hardliners supported Khamenei’s decision, as they usually do in all matters, Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca were at the time the only Covid vaccines provided through the World Health Organization’s Covax facility.

On August 16, the head of Iran's Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Mohammad-Reza Shanehsaz, said a permit had been issued to import Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Shanesaz stressed that Khamenei's concerns were being addressed and that while any source should be reliable "a vaccine's name" was not sufficient reason to stop its import.